Sleeping together: Examining dormitories as architectural types

The book is published at EPFL Press. © EAST Lab / EPFL

A recent publication explores the unique history of dormitories from the Middle Ages to present day. Drawing on a corpus spanning everything from submarines to mountain huts, the authors examine the fine balance between the need for privacy and the function of dormitories as collective spaces, and reflect on the implications for contemporary challenges.

People tend to sleep in dormitories in specific contexts, for a limited period of time or following an unusual event. That’s why they’re typically found in places such as holiday camps, youth hostels, orphanages, military bases, monasteries, hospitals, ferries, overnight trains and refugee camps. The architecture of dormitories has changed considerably over the centuries, following evolving patterns of religious beliefs, social structures, scientific knowledge and political ideologies. As part of a class for final-year Bachelor’s students in architecture – given by the Laboratory of Elementary Architecture and Studies of Types (EAST), within EPFL’s School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering (ENAC) – students set out to explore the architectural history of dormitories from the Middle Ages to present day. The findings of this research are presented in Studies on Types: Dormitories, a book published recently by EPFL Press. In keeping with EPFL’s open access policy, and with the support of the EPFL Library, the book can be downloaded free of charge from the publisher’s website.

Hospices, holiday camps and mountain huts

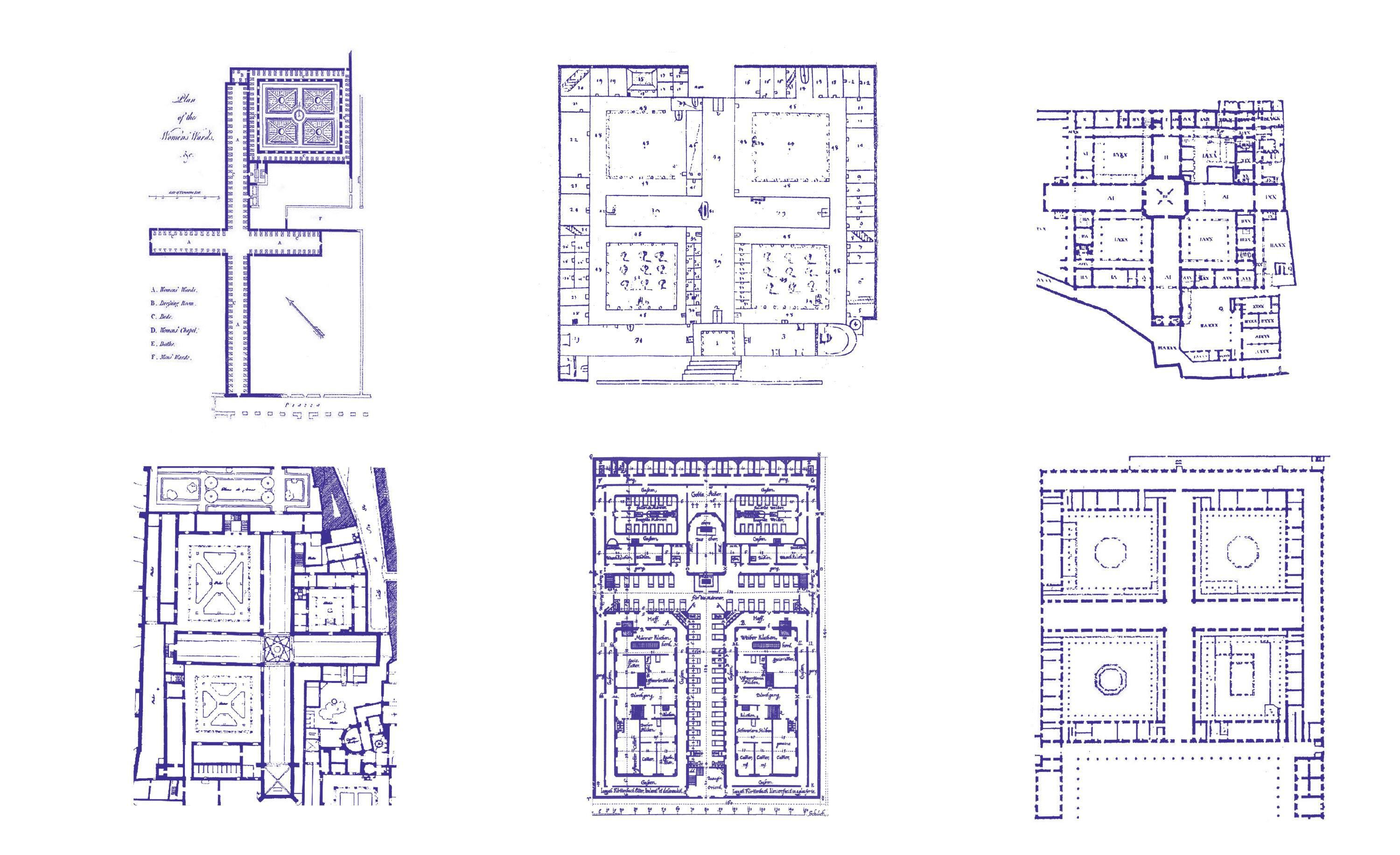

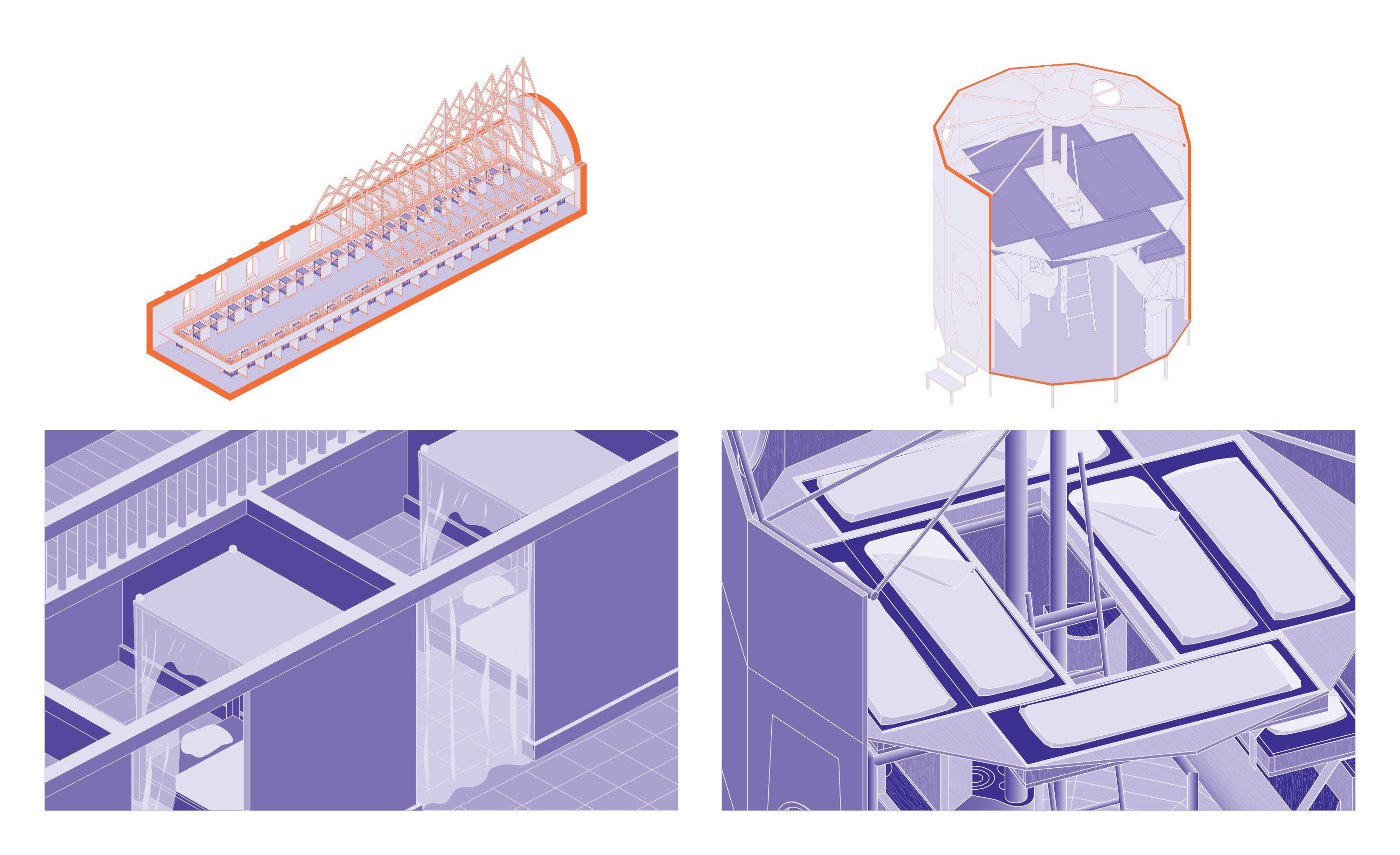

The book opens with a historical and theoretical overview that presents three groups of dormitories. The first example is hospices in the Middle Ages, which provided shelter to pilgrims, the poor and the needy. The authors explain how, in Europe, dormitories for the sick gradually adopted the cruciform plan – from one hand to guarantee the supervision of the sick, anticipating the intention of the panopticon that emerged later, and secondly, as a symbolic religious analogy to Catholicism representing the redemption of humanity from earthly suffering. With advances in scientific knowledge, vaulted ceilings and domed halls were added to these dormitories in the 18th century as a way to ventilate the space. The cruciform plan was ultimately abandoned in favor of a linear layout as responsibility for medical care shifted from the church to municipalities. The idea of dividing dormitories into smaller spaces separated by curtains suspended from the ceiling emerged at the turn of the 20th century. Over time, this layout evolved into the now-familiar concept of individual patient rooms. The two other dormitory examples explored in the book are children’s holiday camps in fascist Italy and the Soviet Union, conceived as tools of indoctrination, and mountain huts, with a focus on the decisive contribution of Swiss architect Jakob Eschenmoser.

The case studies we examined highlighted the importance of providing enough space around each bed to give occupants a sense of privacy.

Reconstructing dormitories from historical sources

The second part of the book features 27 “artefacts” – dormitories from different eras that EPFL students analyzed and reproduced based on historical drawings in order to gain insight into their form, content and purpose. “We learned a lot from proceeding in this way,” says Prof. Anja Fröhlich who, along with Prof. Martin Fröhlich, heads EAST lab assisted by Tiago P. Borges, Vanessa Pointet and Lara Monti in this research project. “For instance, the case studies we examined highlighted the importance of providing enough space around each bed to give occupants a sense of privacy” Professor Fröhlich adds.

In one example, the students studied a sanatorium built to treat children suffering from tuberculosis. They noted that the beds were closely spaced – perhaps as a way to reassure the young patients – and that deck chairs were placed near a window to bring light into the dormitory, which was an integral part of patients’ treatment. As research into the disease progressed, windows and ventilation became essential components of these spaces – along with beds on wheels, which allowed patients to be moved out onto the terrace. Architects also took a growing interest in patients’ view from their beds, to the extent that, in some cases, this became the starting point for their designs.

The students examined dormitories of all flavors, from an Indian monastery, a London hostel, and a Russian sleeper carriage to an Italian holiday camp, a Swiss mountain hut, and a German fire station dormitory. “Future students will be able to use this corpus as a diverse, evidence-based resource to inform their thinking – perhaps for designing new dormitories or modernizing existing structures,” says Prof. Anja Fröhlich. According to Borges, this compendium of historical dormitories could also prove instructive and thought-provoking for practicing architects: “We feel it’s important to understand optimal approaches to ‘sleeping together’ and communitarian values while catering to individuals’ well-being. These insights could help architects tackle the major challenges of our time, such as pandemics, conflicts and natural disasters – all of which involve mass displacement and call for emergency shelter.”

We enjoy exploring spaces that, on the surface, seem mundane because they’re so commonplace. They’re rarely the subject of historical and architectural research.

From dormitories to gas stations

The book is the first in a series that EAST plans to publish on “types,” exploring unique, recurring elements in architecture. Students taking the next class will turn their attentions to gas and service stations linked to sustainable mobility. “We enjoy exploring spaces that, on the surface, seem mundane because they’re so commonplace,” says Prof. Anja Fröhlich. “They’re rarely the subject of historical and architectural research. But, in our view, examining such spaces in a structured, deliberate manner is immensely valuable for architectural and basic research – not least because our discipline is evolving at a rapid pace. Understanding architectural types from the past provides insight into contextual changes and developments. This knowledge leaves us better equipped to address future challenges.”