How can we make our housing less heteronormative?

© Murielle Gerber / 2021 EPFL

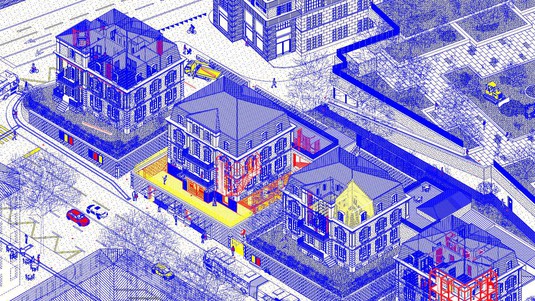

An EPFL architecture student’s radical new approach to the layout of typical city-center buildings in Lausanne, and how we inhabit the spaces we live in, may just revolutionize our ways of thinking.

A washing machine as a living room’s centerpiece. A walk-though closet that becomes a door – and doors that become mirrors. An open-air space on the roof for entertaining. A “communal kitchenless kitchen.” Glazed facades that reveal the interiors of buildings, above all the basement. Welcome to the “queer” house – or at least one that’s less heteronormative, as conceived by a young EPFL graduate in architecture.

Let’s face the facts: the ways in which our living spaces are arranged has not changed much for the best part of two centuries. The same cannot be said, however, of our lifestyles. What’s worse is that the way in which our rooms are laid out, as originally designed by men, limits the way we live. That’s the theory put forth by Claire Logoz, whose Master’s thesis explores heteronormative architecture. EPFL’s DRAG Lab association, of which she is a member, plans to develop a new class that explores architectural norms – a topic currently missing in EPFL’s architecture curriculum.

An inclusive vision

Everything evolves with time: language, which has become progressively more inclusive, and social attitudes, as reflected in new laws that address inequality towards minorities. But what about our homes? “I believe that the design of our homes has a direct impact on our way of living. Architecture exerts a social power over us; it’s clear that we’re shaped by the spaces around us,” says Logoz. A feminist since childhood, even before she knew what the word meant, Logoz decided to channel her activism into academic research. “I read everything I could get my hands on about the relationship between gender studies and architecture. The first articles date back to the 1990s, but nothing has really been done to turn those ideas into concrete projects. That’s kindof surprising.”

After spending a semester conducting theoretical research, Logoz decided to apply her findings to four villas urbaines – a type of housing specific to 19th-century Lausanne. In her work, she completely redesigned the layout. “My final design is for everyone, not just young free-thinking urbanites. Traditional families could also comfortably live in these spaces,” says Logoz.

Honing reflections with humor

As a theater-lover, Logoz’s ideas for “alterations” naturally have their roots in set design. Some changes she proposes are symbolic, such as walk-through closets that serve as doors, alluding to the fact that “the closet” has for decades been a symbol of the shame of homosexuality. She has humorous ideas as well, such as replacing a fireplace with a washing machine to create a “living laundry room.” For all its playfulness, however, Logoz’s offbeat approach intends to hone our ways of thinking. “American architect Frank Lloyd Wright moved the fireplace to the center of the living room to make it a space for relaxation. But only men were able to enjoy this, because the women were busy with household chores,” says Logoz. By placing a washing machine at the house’s center, she pays homage to the materialist feminists of the 1960s who decried the “invisibility of domestic work.”

Inspired by Playboy

Surprisingly, Logoz also found inspiration in architects featured in Playboy magazine, who attempted to “liberate the playboy” from architecture designed for a nuclear family. “For the building’s pool, I replaced the voyeuristic windows favored by these architects with mirrors, to reflect back positive body images to its users. And the changing rooms are, of course, gender neutral.”

Logoz has also turned stairways into "stairs of interaction:" places where residents can meet socially and relax. A system of pivoting doors and curtains enables them to create private spaces and independent entrances for apartments. These imaginative designs allow the layout of an entire building to be modified according to individual needs. “Today’s families are made, split apart and formed again in new ways. It’s time architecture caught up with that," says Logoz.

Claire Ana Logoz, «Catalogue non exhaustif d’altérations performatives», supervisé par Dieter Dietz, Jo Taillieu, Quand-vinh Linh, Julien Carboni Lafontaine, September 2021.