Watching single protons moving at water-solid interfaces

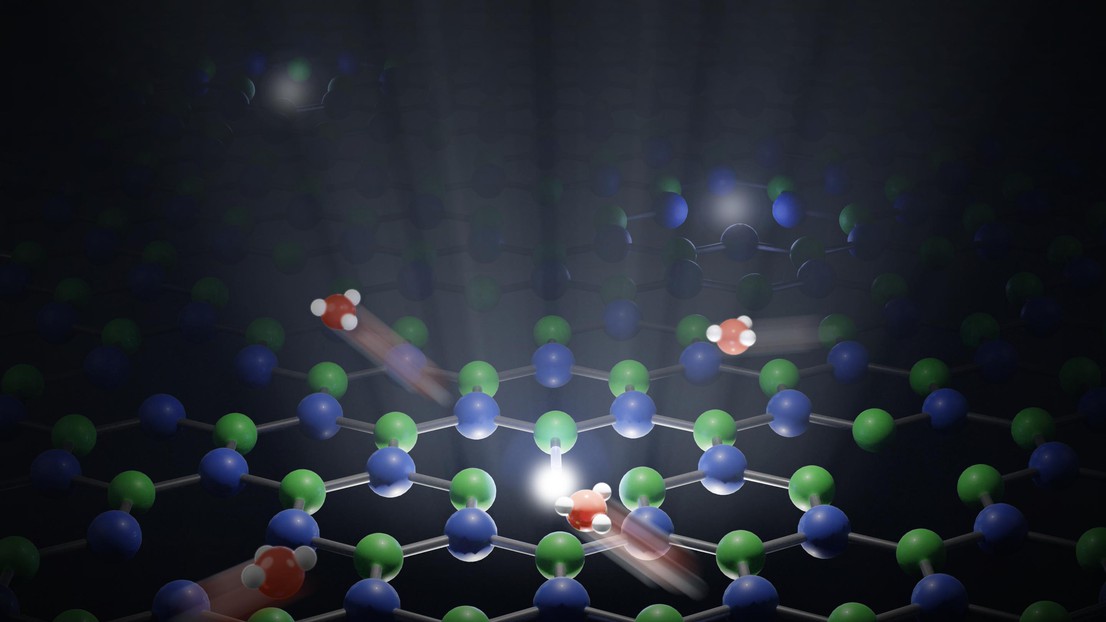

© Vytautas Navikas 2020 EPFL

Scientists at EPFL have been able to observe single protons moving at the interface between water and a solid surface. Their research reveals the strong interactions of these charges with surfaces.

The H+ proton consists of a single ion of hydrogen, the smallest and lightest of all the chemical elements. These protons occur naturally in water where a tiny proportion of H2O molecules separate spontaneously. Their amount in a liquid determines whether the solution is acidic or basic. Protons are also extremely mobile, moving through water by jumping from one water molecule to another.

Proton transport at water-solid interfaces

The way this transport process works in a body of water is relatively well understood. But the presence of a solid surface can dramatically affect how protons behave, and scientists currently have very little in the way of tools to measure these movements at water-solid interfaces. In this new study, Jean Comtet, a postdoctoral researcher at EPFL’s School of Engineering (STI), has provided the first-ever glimpse of the behavior of protons when water comes into contact with a solid surface, going down to the ultimate scale of single proton and single charge. His findings, published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, reveal that protons tend to move along the interface between these two mediums. The study benefited from the help of researchers from the Department of Chemistry at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris who carried out simulations.

Crystalline defects

Comtet studied the interface between water and a crystal of boron nitride, an extremely smooth material. “The surface of the crystal can contain defects,” says Comtet. “We found that these imperfections act as markers, reemitting light when a proton binds to them.” Using a super-resolution microscope, he was able to observe these fluorescence signals and measure the position of the defects to within around 10 nanometers – an incredibly high degree of precision. More interesting still, the study revealed new insights in the way crystalline defects are activated. “We observed defects on the surface of the crystal lighting up one after another when they came into contact with water,” adds Comtet. “We realized that this lighting pattern was produced by a single proton jumping from defect to defect, generating an identifiable pathway.”

A major experimental breakthrough

One of the key findings of the study is that protons tend to move along the water-solid interface. “The protons keep on moving, but hugging the surface of the solid,” explains Comtet. “That’s why we see these kinds of patterns.” Aleksandra Radenovic, professor at EPFL’s Laboratory of Nanoscale Biology (LBEN), adds: “This is a major experimental breakthrough that furthers our understanding of how charges in water interact with solid surfaces.”

“Our observations, in this specific context, can easily be extrapolated to other materials and environments,” says Comtet. “These discoveries could have important implications in many other fields and disciplines, from understanding biological processes at the cell-membrane interface to designing more efficient filters and batteries.

FUNDING EPFL

This work was financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation Consolidator grant (BIONIC BSCGI0_157802) and CCMX project (Large area growth of 2D materials for device integration). E.G. acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation through the National Centre of Competence in Research Bio-Inspired Materials.

FUNDING COLLABORATORS

The quantum simulation work was performed on the French national supercomputer Occigen under DARI grants A0030807364 and A0030802309. M.-L.B. acknowledges funding from ANR project Neptune. K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the Elemental Strategy Initiative conducted by MEXT, Japan, and CREST (JPMJCR15F3), JST.

DOI : 10.1038/s41565-020-0695-4