Using 3D printing to make prosthetics for Colombia war victims

© 2019 EPFL Alain Herzog / prothèse en plastique recyclé

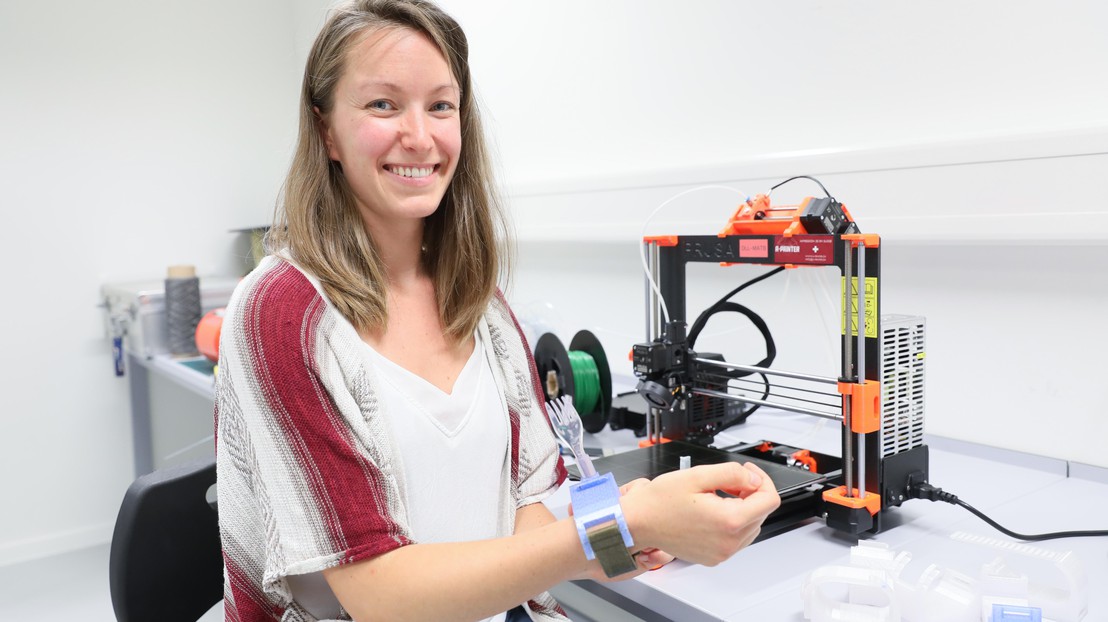

Summer series – Student projects. For her Master’s project, Emylou Jaquier decided to tackle the growing problem of plastic waste. She sifted through EPFL garbage bins to collect different types of plastics and test how they could be used in 3D printing.

Emylou Jaquier hopes that one day plastic will be recycled rather than burned, tossed into the sea or left to decompose into microparticles that accumulate in fishes’ stomachs. These are high hopes, but she is taking concrete steps to get there. Through her Master’s project, she is developing ways to not only recycle a wider variety of plastic, but also use recycled plastic in 3D printers to make inexpensive prosthetics for Colombia war victims. Her research is being carried out jointly by EPFL’s Laboratory for Processing of Advanced Composites and Universidad de los Andes in Colombia.

© 2019 EPFL Alain Herzog / reuse plastics from our trash cans

Currently PET is the only kind of household plastic that is recycled in Switzerland, but it is actually just one of seven varieties. “What I found really interesting in this project was being able to test several different types of plastic and study each one’s behavior. I initially chose five but ended up working with only three. Unfortunately my time was limited, otherwise I would’ve tested them all!” says Jaquier. She dug through garbage bins on the EPFL campus and collected various types of everyday plastic waste – empty water bottles, bottle caps, cafe latte cups, yogurt containers, milk bottles and cling wrap, for example – which she then used to make plastic threads that could be fed into a 3D printer. She made threads of polypropylene, polystyrene and high- and low-density polyethylene, a task that required delving into a new field. “I have a background in mechanical engineering, so designing prosthetics wasn’t really a problem. What was hard was the materials-science aspect of the project. I took some classes but also learned a lot as I went along,” she says.

© 2019 EPFL Alain Herzog / The melting temperature changes according to the plastics

One of the materials-science challenges she faced was juggling the plastics’ different melting points: 260°C for PET but just 130°C for the polyethylene used in bottle caps, for instance. “The plastics should be kept separate, especially if we want to recycle them several times – which would make sense if our goal is to reduce waste. We also need to make sure that the plastics don’t break down after being melted several times,” says Jaquier. Another factor to keep an eye on is the threads’ diameter. “The ideal diameter for a 3D printer is 1.75 mm, but the actual diameter can vary depending on how the thread has been pulled.” And of course, enough used plastic must be collected to create the right amount thread. “Even with 140 bottle caps, I only had enough material to fill a quarter of the spool.”

Two weeks in Colombia

Thanks to the collaboration with the Omnis Institute, the support of the CODEV, the Center for Cooperation and Development of EPFL, the work with the University of Los Andesand the contacts made with Todos Podemos Ayudar Fundacion, by Felipe Betancur, Jaquier was able to spend a couple of weeks doing field research in Colombia. There she took part in a workshop, showed her prototype and met with other researchers who are also developing low-cost prosthetics and 3D printing threads, including based on natural fibers. Now she’s certain that she would like to pursue a career in plastics-recycling R&D.