“This is an absolutely incredible organism!”

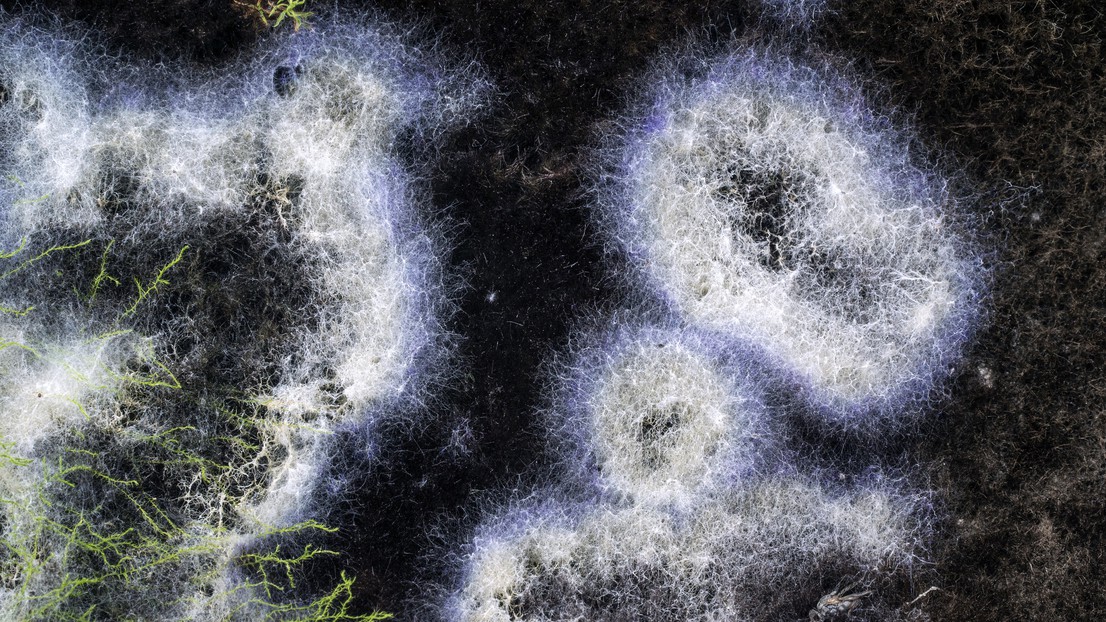

Réseau de filaments, mycélium © Mario Del Curto

For his exhibition « Fungi, un monde sans fin », organized by CDH-Culture, photographer Mario Del Curto traveled the world photographing different types of fungi in the wild, in agriculture, and in scientific labs. The photos are displayed at the Rolex Learning Center until 23 February 2025.

Why did you choose to photograph fungi?

When I tell someone that I work with mushrooms, everyone imagines a new book on those that we can eat: morels, chanterelle, etc. But in fact, no. 25% of the fungal world is invisible. In the exhibition, I focus on the mycelial network, which is essentially an underground network made of filaments that are of the order of a nanometer. There is this evolution from the filament that manifests itself in the extraordinary force of the living.

The more I continue in this work on plants and fungi, the more I have the feeling that the separation of species into kingdoms is a somewhat arbitrary, scientific separation, to compartmentalize. When we look at the forms of these species, we realize that sometimes a mushroom looks like an animal, sometimes a plant. Sometimes the plant looks like a mushroom, sometimes the plant looks like a human. This work leads me to question what it means to be alive on this planet.

How did this interest in fungi start for you?

I had done some work on the relationship between humans and plants. There was a book called Humanités végétales, and at the end of the book, I discussed the issue of agronomy and mushrooms with Katia Gindro from Agroscope in Changins, and she contaminated me a little. What do this mean? She told me about what a mushroom was, the ways in which mushrooms exist, the places where they could be found. And I said to myself: ‘this is an absolutely incredible organism with an absolutely phenomenal capacity for adaptation!’ What I also found interesting was the fact that animals and mushrooms have evolved together for a long time. And it’s true that from a genetic point of view, mushrooms are closer to animals than to plants. There’s also a part that I really like in my work in general, which is the contribution of amateurs to science and knowledge.

What was your experience of working in laboratories?

It is very particular because now, research, whether in biology, physics or chemistry, takes place in the same labs. In general, it is a bit of organic matter and mostly large computers. Another characteristic of my work is that I have always remained at the level of what the eye sees. I have not used a microscope or a telescope, but at the same time, I told myself that it is still strange to carry out photographic work on an organism of which 25% is invisible. So I worked a little with the electron microscopy department at the University of Geneva for the truffle, and for other mushrooms. What interests me in this structure is that it is not very different from a tissue fixed on a bone.

How did you design this exhibition for the Rolex Learning Center, as it is quite a unique building?

I found it interesting to bring a bit of nature into this “high-tech” environment of EPFL, where we can sense the beginnings of a humanity that is a little out of touch with reality, that lives a lot on screens and with technology.

The Rolex space is difficult, but the structure is good. I think it is important to have a photographic presence in a student environment. I hope that this exhibition gives the opportunity to look and discover another way of being. I think it is quite complementary.

What do you think we can learn from fungi?

A bit of a mirror image in the sense that there are pathogenic fungi, but also many fungi that work in a collaborative way, that is to say that they need other species, like trees for example. A mutuality is possible. Sometimes I tell myself that mycological life, mycorrhizal life and that of the mycelium, is not very far from human society. But perhaps human society is more in conflict than fungi are among themselves. Fungi also defend their territory, but at the same time, they are very often in situations of mutual aid and mutualism.

There is this widespread idea that we can see in the press or in certain films that fungi are going to save the world. But the ones who can really save the world or humanity are humans themselves.