The upside of downtown

© 2013 EPFL

Dense, diverse city centers reduce the need for personal mobility, making cities more sustainable.

The population of the Lake Geneva Region is growing rapidly. According to the Federal Institute for Statistics, the population of the cantons Vaud and Geneva combined is projected to grow by 21.5% to hit 1.4 million inhabitants by 2035. With the main transportation arteries already at or beyond maximum capacity during peak hours, housing prices surging, and social services such as daycare often hard to come by, the debate is heated on whether the region can sustain this runaway growth, and if so, how.

According to Professor Andréa Bassi, we are witnessing nothing short of the emergence of a new metropolitan area, the “Métropole lémanique,” and it’s limited by one main factor: mobility. Many of us drive our cars to work every day, to run errands, or to go for a run or walk in the park. Often, there’s a lack of alternatives; residential areas are separate from commercial zones, and parks and recreational areas are sparsely distributed within urban centers. This separation has made us increasingly dependent on our cars, to the point that we willingly put ourselves through the endless stop-and-go of driving on congested streets.

This separation didn’t come about by chance. In emerging industrial societies, it was important to separate residential and industrial areas, primarily to protect residents from the noise and pollution of factories. Different uses of land that were considered incompatible were segregated into zones, and “zoning” was born. But with the shift towards a silent, less polluting tertiary economy, the arguments in favor of zoning are no longer convincing. Nonetheless, the practice still prevails.

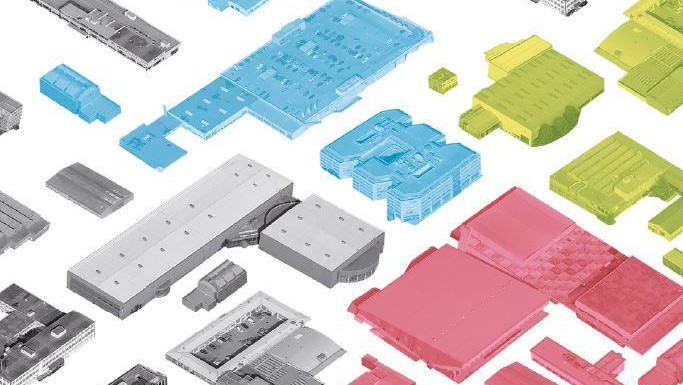

As physical mobility reaches its limits, Bassi predicts that it will be replaced by virtual mobility: that of different types of media and information. For the past four years, he and his team of architects and urban planners in the Laboratory of Urban Architecture (LAURE) have been studying urban solutions to adapt to this new reality. Rather than protecting inhabitants by creating distance between them and industry, he argues that today’s urban planning should focus on optimizing flows – of people, goods, information – by building denser, more diverse cities. The response developed in his research group, is to limit our dependence on mobility by designing multifunctional urban spaces that combine residential, commercial, and recreational roles.

Humans, however, are creatures of habit, and the ideal of living in the tranquil countryside and working in the city is deeply rooted in our culture. “As architects,” says Bassi, “we have to show people other alternatives and convince everyone, from the businessman to the baker, of the advantages of living in denser and more diverse urban centers. Once they realize that they no longer have to commute to work, that social services such as daycare and schools can be found nearby, and that they can do their shopping, go to the movies, and eat out without having to get into a car, they just might be persuaded.”

Although some neighborhoods are spontaneously converting to a more mixed format, they can only do so if their buildings allow for it. In Switzerland, many buildings built in the 1960s can’t be renovated, so spontaneous adaptation has been slow, with the exception of a few industrial parks. New projects must keep this in mind; although they can be designed with multifunctional use in mind, the design should include a degree of ambiguity, allowing them to evolve.

The acceptance barrier to these new concepts is still quite high, says Bassi. Residents will only feel comfortable downtown if they perceive the quality of life to be at least as high as that in the suburbs. Without a feeling of space, of openness, they are not likely to be convinced. “These are exciting times to be an architect,” says Bassi, who participated in the urban plan of the Praille area in Geneva. “For years we’ve been drawing solids. Now we get to start drawing empty spaces.”

And the challenges go beyond persuading the residents of the advantages of dense, diverse urban centers; urban planners run into obstacles on an administrative level as well. Zoning, still the predominant urban planning paradigm, requires the unambiguous attribution of a zone type to each area. The result is a two dimensional map. But what about multifunctional buildings that have commercial and residential spaces on different floors? It’s high time for a new approach – with any luck, before long, farmers will be planting crops on urban rooftops!