“The human condition exists through the power of storytelling”

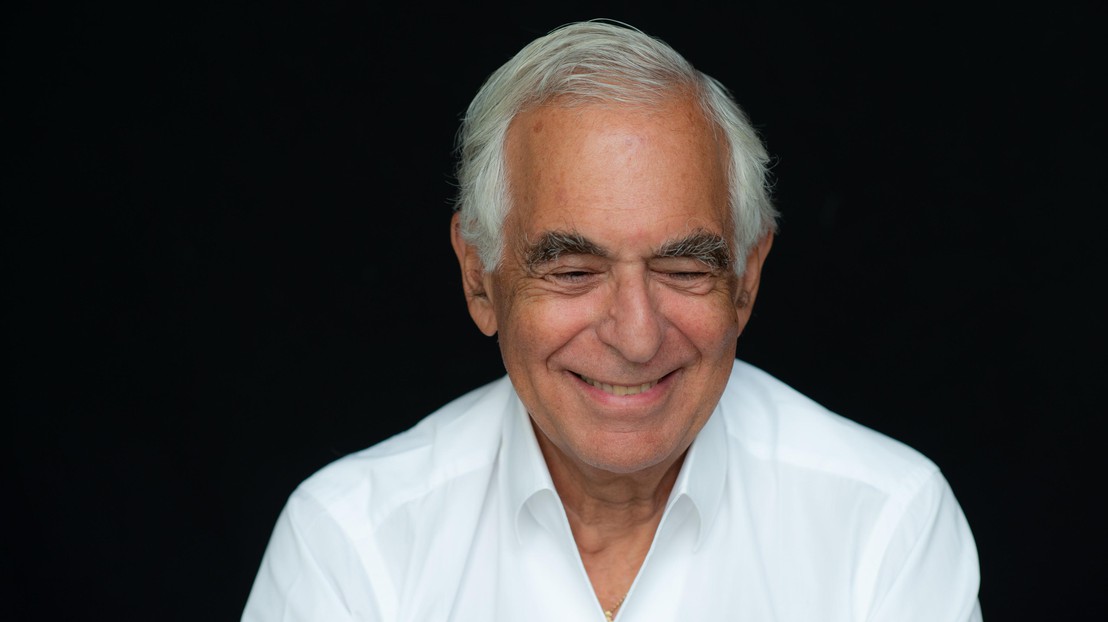

Metin Arditi, a physics graduate from EPFL’s precursor EPUL - Photo: DR / Metin Arditi

A successful writer, philanthropist and business man: Metin Arditi, a physics graduate from EPFL’s precursor EPUL, has followed each of these pursuits with passion and a remarkably free spirit. The winner of numerous literary awards as well as an EPFL Alumni Award, Arditi sat down to speak with us about his career path and his enduring ties with our School.

What memories do you have of your childhood in Turkey?

I was born in Ankara in 1945, and my family moved to Istanbul when I was three months old. I lived there until I was seven. I remember those as happy years, living within a highly cosmopolitan society. But I also recall a kind of “Europe complex” within my family: my parents were big admirers of European culture in general, and of Switzerland in particular.

Looking back, that seems unfair because Turkey itself has a very rich culture. At home you could hear five different languages being spoken. I think it’s important to make the distinction between culture and civilization – a distinction I didn’t understand myself until very late in life. Civilization is the ability for people to live together, and it’s very strong in Turkey and in my family. I believe it’s much more important than culture.

My parents saw Switzerland as a reassuring, timeless country. They believed so strongly in this Swiss myth that they enrolled me in a boarding school in Paudex, in Vaud Canton. I started there when I seven and stayed until I was eighteen.

Were culture and the arts already part of your life during this period?

I saw very little of my parents while I was at boarding school. My father came to Switzerland for business about twice a year and we would spend a weekend together each time. My mother came to Europe for a month each summer and we often traveled to Auvergne or Italy. I spent the other summer month at the boarding school, which ran a program for children who went there to learn French. But I wasn’t required to attend the morning classes. I was alone and spent my time fishing and reading. That’s where my love of reading began.

But it’s actually the arts more than reading that helped me during that period. What really saved me was theater in particular. We put on plays like The Miser by Molière and The Bear by Chekhov, with performances at the end of the school year. The stage director was Paul Pasquier, a famous actor and director, and one day he said to my mother: “You know, Metin is a very gifted actor.” And my mother replied: “Whatever you do, don’t tell him that!” My parents didn’t feel acting was a serious profession.

I never considered acting as a career choice out of respect for them, but I’ve always had a taste for it. Recently, I was happy to be able to play a role in the film adaptation of L’enfant qui mesurait le monde, which will come out in 2024.

What prompted you to attend what was then EPUL and to select physics as a major?

My father wanted me to be an engineer, but I wasn’t keen on that at all. I couldn’t see myself working as a mechanical engineer, for example. But I was immediately drawn to physics. It’s a more theoretical discipline, oriented more towards philosophy, and the people who practice it tend to be a little different.

My first years as a physics student were hard. I struggled with subjects like the basics of metals and industrial design. We had a heavy courseload – classes started at 7am or 8am depending on the semester and ran until 6pm. That was Monday to Friday, and we also had classes on Saturday mornings. I don’t think this military-style approach is the most effective, because that’s an age when you need time to reflect and work on projects, either alone or in a group. I felt more comfortable in the final years when we had more leeway to explore our imagination and present our findings.

After you graduated from EPUL, you enrolled in Stanford’s MBA program in 1968, then returned to Europe and started working as a McKinsey consultant. But you left the firm after just two years. Why was that?

I really liked the analytical nature of the work at McKinsey – analyzing costs and operations, for example. And we always had excellent, enriching relationships with our business clients. But I hated the atmosphere at McKinsey. When I joined the firm, I didn’t realize just how much I’d been marked by my 11 years at boarding school. I had trouble accepting the authority, hierarchical structure and extremely rigid organization. I needed to be free and independent – I was a bit of a loner in reality. I left McKinsey after exactly two years: I started on 7 July 1970 and left on 7 July 1972, at 27 years old.

While managers like to be part of a team, entrepreneurs are more independent by nature and prefer to go it alone. I realized that I fell into the second category.

You then had a very successful career in the real-estate business. What attracted you to that industry?

After I left McKinsey I returned to California. My idea was to seek out young, high-potential companies and invest in them. After 12 years I’d built up a portfolio of companies that together employed around 150 people. But as someone who didn’t like to receive orders, I also didn’t like to give them. It was only then, at the age of 40, that I understood the colossal difference between a manager and an entrepreneur. While managers like to be part of a team, entrepreneurs are more independent by nature and prefer to go it alone. I realized that I fell into the second category. I sold all my holdings in these companies in 1984.

The real-estate industry fit in well with my solitary nature. It’s a field where you can build up a large business with just a small team. And I enjoyed every aspect of it: the negotiations and risk-taking, as well as ground-up construction work and renovating old buildings.

How did you get into writing?

By the late 1980s, real-estate prices on the deals I was working on had reached surreal levels. I felt it was important to take a step back from all that. Looking around me, I saw many real-estate investors had inflated egos just because they handled large sums of money. That scared me. There was no reason why I wouldn’t eventually become just as vain. I took to reading La Fontaine’s fables on a daily basis, and they were a huge help. La Fontaine was a masterful French writer but his philosophy – based on wisdom, modesty and restraint – is closer to Eastern schools of thought.

Then in 1992 I met Prof. Michel Jeanneret at a gala dinner. We were both admirers of La Fontaine, and this formed the basis of our friendship. He asked me to speak at a seminar on the author, and that speech eventually expanded into a book. Since then, I’ve never stopped writing. Another decisive moment came when I met Jeanne Hersch, a philosopher. I was fortunate to have known her during the last decade of her life and to have benefitted first-hand from her vision and scholarship. I still remember our extremely intense, enlightening discussions.

You’ve juggled many different activities over the years – how do you find time to write?

I write every day and I can write anywhere – in my bedroom, on a train, it doesn’t matter. Once during an interview for a radio show, the presenter asked me where the last place was that I’d written, and the answer was in an elevator! I write by hand in large notebooks that I always carry with me. When I travel, I take pictures of the pages and send them to my assistant who types them into a computer. The more regularly you write, the easier it gets because the book you’re working on, its ambiance and so on, are always on your mind.

Writing is about trying to describe what’s within the human heart – which by definition is impossible.

Is writing an enjoyable or painful experience for you?

It’s mainly a painful experience because as a writer, you always feel like what you’re doing isn’t good enough. Writing is about trying to describe what’s within the human heart – which by definition is impossible. You want to convey a truth, but it’s a never-ending process. Something is never quite right. And I’m constantly afraid I’ll betray my characters. I know that may sound silly, but I genuinely want to be as true to them as possible. That often means rewriting passages 30 or even 50 times, depending on their importance, until they “sound right” – until the emotions or behavior of my characters are genuinely consistent with their reality.

The feedback I’ve gotten on my books gives me hope that readers get something out of them, which for me is the whole point. The human condition exists through the power of storytelling, and literature plays a key role in our history. As individuals, we can’t grow in a vacuum – we need something to hold a mirror up to.

Do you have a favorite book among those you’ve published?

No, because all my books reflect who I am in one way or another and they all tell the same story – they’re all about lineage – even though they go about it in different ways. All my novels are personal, from Turquetto to L'homme qui peignait les âmes. The theologist Daniel Marguerat attended the launch event for my most recent book, Le bâtard de Nazareth, and he remarked that “Actually, Jesus in the book is you.” And I said well, yes, he was right!

Is there a book you haven’t written yet but would really like to?

I write a lot and am lucky enough to be able to write about subjects that are important to me, so I’d say the answer is no. My next book will come out in March 2024, and I’m currently working on a Roman-era saga that spans Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire. It’ll be published in four volumes. Research for this work has taken me to Istanbul quite a lot lately, and it’s been wonderful. I’ve also published three “lover’s dictionaries” – on Switzerland, Istanbul and French wit – and I just signed a contract for a fourth one: a sinning lover’s dictionary!

When it comes to philanthropy, you can’t do things by halves. I only select initiatives that are within my reach and that I’m ready to invest in fully.

You’re also known for your philanthropy work through the Arditi Foundation. What prompted you to create the Foundation and then devote so much time to it for decades?

I was a lecturer at EPFL when I started my business career, but I eventually had to give up teaching due to the travel and other commitments for my company. By creating the Foundation and giving out awards to university students, that gave me a way to stay in touch with the academic world. So at first, it was purely for selfish reasons!

Another factor was that in speaking with my nephew, I learned that he received his University of Geneva law degree by mail. That was unthinkable for me after my experience in the US, where graduation ceremonies are important milestones. I wanted to change that by introducing an award for university students and holding a proper ceremony at the University of Geneva. At EPFL, we started by handing out awards in mathematics and physics, and then after I met Prof. Jean-Marc Lamunière, we created one together for architecture.

The Foundation has rolled out several initiatives on issues dear to me, like Instruments of Peace in Geneva, which funds musical educational programs for Palestinian and Israeli children and supports schools and conservatories in both regions. When it comes to philanthropy, you can’t do things by halves. I only select initiatives that are within my reach and that I’m ready to invest in fully.

On a personal level, it was through the Foundation that I met Michel Jeanneret and Jeanne Hersch, so it’s been of direct benefit for me, too.

EPFL has been a constant throughout your career – you were a student there, a lecturer, the chair of its cultural committee and a member of its strategy board. Why did you keep such close ties to the School even though your career took you away from science and engineering?

Because I’m so very sentimental! It was my school and I’m still highly attached to it. When I was there, there were only 1,000 students in total and 17 in the physics department. I’ve seen the School grow and evolve over the years, especially when Patrick Aebischer was president. It’s also worth pointing out that Francis Waldvogel, who was president of the ETH Board, had the courage to appoint someone to lead EPFL who wasn’t an engineer. And two of my EPFL professors – Jean-Pierre Borel and Bernard Vittoz – left a lasting mark on me. Bernard was even the best man at my wedding.

Looking back over your atypical and varied career, what advice would you give today’s EPFL students and new graduates?

I don’t give advice. I hate it when people give me advice, and I don’t like to hand it out either. But I do write stories, and I can tell you one story that’s true. While I was studying for the midterm exams during my fourth year at EPUL, a classmate pointed out that our professor hadn’t covered a chapter in our solid-state physics book and that we could be asked about that topic on our final exam. There were no class notes, but there was a book on that topic at the local bookstore. It cost 60 francs, which was a hefty sum for my student budget. So I didn’t buy the book.

About a month later, I took a break from studying and went to the movies to see The Professionals by Richard Brooks. In this film, a woman played by Claudia Cardinale is kidnapped and her husband hires a group of mercenaries led by Burt Lancaster’s character to find her. At one point, Cardinale’s character accuses Lancaster’s of being in it only for the money. He replies that no, he’s doing it because he’s a professional. She asks what it means to be a professional, and he says that it’s someone who puts all the odds on his side. As soon as I got out of the theater, I went straight to buy the book. And sure enough, that topic was on the final exam. I got the highest possible grade on that exam and the next one, which was unusual at the time (success breeds success). Those grades were decisive in getting me into Stanford. That quote from Lancaster’s character has never left me.

1945 Born in Ankara, Turkey

1952 Moves to Switzerland, attends Ecole Nouvelle boarding school in Paudex (Vaud Canton)

1967 Graduates from EPUL with a physics degree

1970 Graduates from Stanford with an MBA

1972 Founds the CODEV real-estate investment company, which later became Financière Arditi

1988 Sets up the Arditi Foundation

2004 Publishes his first book, Victoria-Hall

2005 Appointed to EPFL’s strategy board

2011 Publishes Le Turquetto, which won 25 literary awards

2012 Appointed UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador