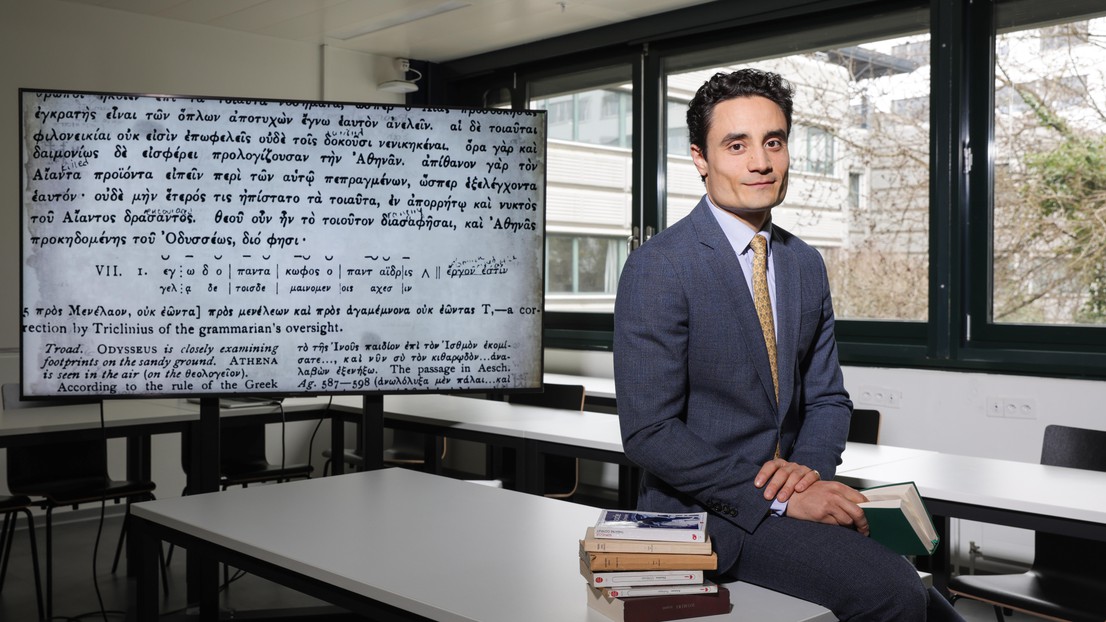

“The frontiers between antiquity and AI fit me very well”

© 2025 EPFL/Alain Herzog - CC-BY-SA 4.0

Sven Najem-Meyer of the Digital Humanities Laboratory explores the intersection of machine learning and classical studies, tackling the challenges of document processing for texts in Ancient Greek. On March 27, he will compete in the finals of “My Thesis in 180 Seconds” at EPFL.

You have just defended your PhD thesis. Can you describe your project in a few sentences?

This project is all about improving document processing pipelines in a low-resource and very domain-specific environment: commentaries on Ancient Greek works.

Document processing is a field of machine learning. It focuses on the steps to go from a physical to a machine-readable document, and to perform higher level textual functions, such as search, on that document. Typically you start by scanning and preparing the document. Then you have to extract texts using Optical Character Recognition, and also extract structure or layout if needed. Once you have structured texts, they can be stored as browsable data and perform advanced information retrieval, entity extraction or large-scale comparison of texts.

For me, the most stimulating part of this work is that all the steps of my document processing pipeline are made highly challenging by the nature of the documents I am working with. Classical commentaries feature an extremely specific and multilingual prose, as they constantly alternate between Ancient Greek, Latin and the commentator’s language, for example English or French. We call this interweaving of languages “code-switching”. So just for extracting the texts, you now have two alphabets — polytonic Greek and Latin — to decipher at once. Add to this the fact that we have very little data and you have a recipe for a very interesting piece of research in my opinion.

How did you choose your thesis topic?

It was pretty straightforward, as it was naturally determined by the research project I am part off, Ajax MultiCommentary. Nevertheless, I was granted some academic freedom and I think my impulse contributed to give the PhD a strong machine-learning orientation, notably with the use of specialised models. As to how I came to study something at the frontiers between antiquity and artificial intelligence, I think it fits me very well. I am an engineer, but I’ve always been fond of the Greek world. This familiarity — if not tenderness — for the source material is a big plus in the life of a machine learning engineer: you can always have a peek at your data when you feel tired of working!

What do you find interesting about your field of research?

The most interesting part is that you always have to find ad-hoc solutions to your problems. This is especially true in the field of natural language processing, where things have evolved so quickly and so drastically during my PhD. No matter the latest LLM, when you’re working in a highly specific environment, you still have to tinker around. And that is both frustrating and exciting.

Why did you choose to do your PhD at EPFL’s College of Humanities (CDH)?

I was admitted in two PhD programs and I had to make a choice which wasn’t easy. I chose the CDH for several reasons. First, I had often come to Switzerland in the past, I had a part of my family living there and I wanted to try live and work there for a while. Second, I knew that EPFL offered a highly competitive environment for PhD students, and I wasn’t disappointed. From computing facilities to broader work-related amenities, everything here is made so that researchers can deliver their best.

When you’re not working on your PhD research, what do you enjoy doing in your free time?

Free time, what do you mean? In the distant era when such fairytale things still existed — about nine months ago, just before the dawn of The Intense Redaction Phase — I remember I enjoyed playing volleyball, reading books about ancient Greece, and watching pre-1960 black-and-white movies. I definitely need to experience this again!