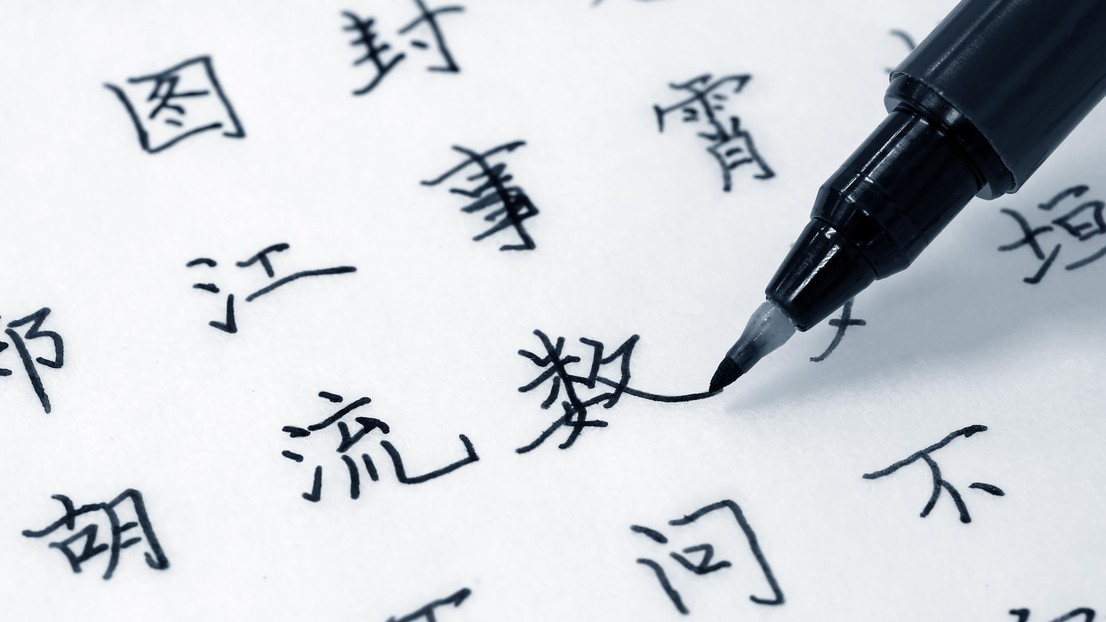

The art of science meets the science of art

© 2021 iStock

In a unique collaboration with ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne, EPFL researchers have developed an algorithm designed to generate some of the world’s first Chinese typefaces, using machine learning.

One-thousand years ago during the medieval Song dynasty, the artist and engineer Bi Sheng invented the first movable type printing technology, using porcelain and wood pieces arranged and organized for printed Chinese characters. It was a system that revolutionized printing.

Fast forward to today and researchers at EPFL’s Computer Vision Laboratory (CVLAB) in the School of Computer and Communication Sciences, working with ECAL’s Master’s programme in Type Design, have perhaps created the next revolution in the art and process of designing digital fonts, developing a machine learning algorithm to generate Chinese Hanzi as images.

Type design involves drawing each letterform using a consistent style. Within each letterform a glyph is an elemental symbol intended to represent a readable character for the purposes of writing. To design a Latin font, the minimum number of characters needed is 26 uppercase letters. Chinese Hanzi script, on the other hand, has 6763 commonly used characters and tens of thousands for more elaborate sets, meaning a typeface can take years to complete.

After two years of studying Latin type design, ECAL student Shuhui Shi approached the Computer Vision Laboratory with this specific challenge, “When I draw Latin typefaces, usually dozens of glyphs are enough for daily usage. But when I tried to apply my type design skills to Chinese I found that it was almost impossible to finish a standard character set with 6763 glyphs by myself. I found many other designers facing same issue. I thought that Machine Learning could possibly help,” she said.

The huge number of Hanzi is clearly a test for human designers but offers opportunities for artificial intelligence, and so the AIZI project was born. The first task was to develop glyphs that could be used to train the AI.

“Shuhui created a large database of characters that were split into very basic components. The idea was, that to design new fonts, someone would only need to design a series of basic components and then they could be assembled automatically to form all of the character sets,” said Mathieu Salzmann, a scientist with the Computer Vision Laboratory. “We then designed algorithms to do the second part – to generate different characters based on these components.”

The algorithm is now able to create tens of thousands of Hanzi as images with an eventual goal to automatically generate Chinese typefaces based on less than 500 Hanzi inputs; the new tool being a contemporary, transdisciplinary approach, standing at the crossroads of design and technology.

For the CV LAB the AIZI project was the chance to work on something new. “Although the technology, called the generative adversarial network, or GAN, is something we often use, working on this kind of problem was a first. GAN is a deep neural network that is aimed at generating images, such as faces, so the idea was to try to use this kind of technology to generate characters,” continued Salzmann.

“For me, this collaboration provided a new vision with which to observe the world. We hope to develop an AI assistant to help designers generate a whole character set with less than 500 human-designed Hanzi. For now, we have a database that contains more than 90-thousand Hanzi and tens of thousands of well-scaled generated Hanzi in the left-right composition. The results need to be optimized in the future,” said Shi.

At ECAL,Matthieu Cortat-Roller, the Head of Master Type Design, who worked closely with Shi, already has ideas for a future project combining design and AI, “Last year in the master’s class we worked on the Syriac script, used in the Middle East since the first century AD, and the big difficulty was that only a few typefaces exist,with a small community of users, and almost no documentation. Students spent a long-time researching and scanning manuscripts online and I think that's the kind of thing machine learning could do quite well.”

But for Cortat-Roller there is a deeper motivation, beyond efficacy, to seeing what AI can bring to this work.

“The number of users of Syriac script today is really scarce and, with the war in Syria, a large majority of them are in Europe, the United States and elsewhere around the world. There are fears of what their culture and identity will become; keeping a writing system when you live in a diaspora is not that easy. For example, with no typefaces, Syriac needs to be written by hand, you can’t just send an email. We are interested in whether machine learning can help preserve cultural heritage through creating a variety of typefaces for the language, enlarging the palette of graphic expression to contemporary usages.”

Back in China, Shi will continue to dive deeper into both machine learning and type design. “I hope Project AIZI will give an easier start to any designer who would like to try Chinese type design. This help from technology should allow them to focus more on their creative ideas without the fear of having to design thousands of characters and hopefully attract more people to try their first Chinese typeface. There is still so much to be done with AIZI and I will do my best to make it happen.”