Superconductor–insulator transition

SuFET-ICMP© 2011 EPFL

Like atomic-level bricklayers, researchers from the US-DOE Brookhaven National Laboratory and the Laboratory of Physics of Complex Matter (EPFL) have used a precise atom-by-atom layering technique to fabricate an ultrathin transistor-like field effect device to study the conditions that turn insulating materials into high-temperature superconductors.

Like atomic-level bricklayers, researchers from the US-DOE Brookhaven National Laboratory and the Laboratory of Physics of Complex Matter (EPFL) have used a precise atom-by-atom layering technique to fabricate an ultrathin transistor-like field effect device to study the conditions that turn insulating materials into high-temperature superconductors. The technical break-through, which is described in the latest issue of Nature (April 28 NATURE 472, pp 458-460 (2011)), is already leading to advances in understanding high-temperature superconductivity, and could also accelerate the development of resistance-free electronic devices.

“Understanding exactly what happens when a normally insulating copper-oxide material transitions from the insulating to the superconducting state is one of the great mysteries of modern physics,” said Brookhaven physicist Ivan Bozovic, leader of the BNL group. ‘’And it’s timely to contribute some new insight just as we celebrate the centenary of discovery of superconductivity (K. Onnes, Leiden, 1911) and 25 years of high-Tc cuprates’ superconductivity (G. Bednorz and K.-A. Mueller, IBM-Zurich, 1986),” added Davor Pavuna, Physics Professor at the ICMP-EPFL.

One way to explore the transition is to apply an external electric field to increase or decrease the level of “doping” — that is, the concentration of mobile electrons in the material — and see how this affects the ability of the material to carry current. But to do this in copper-oxide (cuprate) superconductors, one needs extremely thin films of perfectly uniform composition — and electric fields measuring more than 10 billion volts per meter. (For comparison, the electric field directly under a power transmission line is 10 thousand volts per meter.)

The molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) was used to create perfect superconducting thin films one atomic layer at a time, with precise control of each layer’s thickness. With MBE researchers were able to build ultrathin superconducting field effect devices that allow them to achieve the charge separation, and thus electric field strength, for these critical studies.

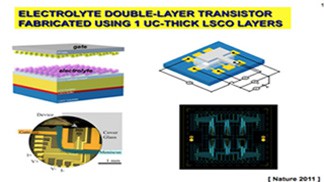

The fabricated devices are similar to the field-effect transistors (FETs) that are the basis of all modern electronics, in which a semiconducting material transports electrical current from the “source” electrode on one end of the device to a “drain” electrode on the other end. FETs are controlled by a third electrode, called a “gate,” positioned above the source-drain channel — separated by a thin insulator — which switches the device on or off when a particular gate voltage is applied to it. But because no known insulator could withstand the high fields required to induce superconductivity in the cuprates, the standard FET scheme doesn’t work for high-temperature superconductor FETs. Instead, electrolytes were used, liquids that conduct electricity, to separate the charges. In this setup, when an external voltage is applied, the electrolyte’s positively charged ions travel to the negative electrode and the negatively charged ions travel to the positive electrode. But when the ions reach the electrodes, they abruptly stop, as though they’ve hit a brick wall. The electrode “walls” carry an equal amount of opposite charge, and the electric field between these two oppositely charged layers can exceed the 10 billion volts per meter goal (see Fig.1).

In this setup, when an external voltage is applied, the electrolyte’s positively charged ions travel to the negative electrode and the negatively charged ions travel to the positive electrode. But when the ions reach the electrodes, they abruptly stop, as though they’ve hit a brick wall. The electrode “walls” carry an equal amount of opposite charge, and the electric field between these two oppositely charged layers can exceed the 10 billion volts per meter goal (see Fig.1). The result is a field effect device in which the critical temperature of a prototype high-temperature superconductor compound (lanthanum-strontium-copper-oxide) can be tuned by as much as 30 degrees Kelvin, which is about 80 percent of its maximal value — almost ten times more than the previous record (see Fig.2).

The result is a field effect device in which the critical temperature of a prototype high-temperature superconductor compound (lanthanum-strontium-copper-oxide) can be tuned by as much as 30 degrees Kelvin, which is about 80 percent of its maximal value — almost ten times more than the previous record (see Fig.2).

The scientists have now used this enhanced device to study some of the basic physics of high-temperature superconductivity.

One key finding: As the density of mobile charge carriers is increased, their cuprate film transitions from insulating to superconducting behavior when the film sheet resistance reaches 6.45 kilo-ohm.  This is exactly equal to the Planck quantum constant divided by twice the electron charge squared — h/(2e)2. Both the Planck constant and electron charge are “atomic” units — the minimum possible quantum of action and of electric charge, respectively, established after the advent of quantum mechanics early in the last century.

This is exactly equal to the Planck quantum constant divided by twice the electron charge squared — h/(2e)2. Both the Planck constant and electron charge are “atomic” units — the minimum possible quantum of action and of electric charge, respectively, established after the advent of quantum mechanics early in the last century.

(see Fig.3).

“It is striking to see a signature of such clearly quantum-mechanical behavior in a macroscopic sample (up to millimeter scale) and at a relatively high temperature,”. Most people associate quantum mechanics with characteristic behavior of atoms and molecules. This result also carries another surprising message. While it has been known for many years that electrons are paired in the superconducting state, the findings imply that they also form pairs (although localized and immobile) in the insulating state, unlike in any other known material. That sets the scientists on a more focused search for what gets these immobilized pairs moving when the transition to superconductivity occurs. “Although there were some preliminary discussions, it is striking to provide the evidence for pairs at both sides of the quantum transition,” emphasize the co-authors.

Superconducting FETs might also have direct practical applications. Semiconductor-based FETs are power-hungry, particularly when packed very densely to increase their speed. In contrast, superconductors operate with no resistance or energy loss. Here, the atomically thin layer construction is in fact advantageous — it enhances the ability to control superconductivity using an external electric field.

“This is just the beginning,” Bozovic said. “We still have so much to learn about high-temperature superconductors. But as we continue to explore these mysteries, we are also striving to make ultrafast and power-saving superconducting electronics a reality.” “And, what really makes us very happy is to see our EPFL graduate, Guy Dubuis, to actively contribute to this work and publication already in his first year of the doctoral school. We obviously offer an excellent education at the EPFL as our graduates quickly perform at the world’s foremost scientific level,” concluded Pavuna.

This joint research effort was funded by the DOE Office of Science and the Swiss National Science Foundation and actively supported by the BNL and the EPFL.