Simulations show residents' role in shaping urban space

© 2011 EPFL - André Ourednik

Top-down incentives such as housing subsidies aimed at steering urban development often fight an uphill battle against a poorly understood bottom-up force, the product of an entire population of individuals and families trying to live their lives and make ends meet. In a recent issue of the French Revue Urbanism, Prof. Jacques Lévy and Dr. André Ourednik (CHÔROS Lab, EPFL) presented the results of a computational study designed to tease out the rules guiding urban development and the reasons why some incentive strategies might be successful when applied to one population, while completely backfiring when applied to another.

Theoretical research on urban development has a history of considering human beings as rational agents, basing their decisions about where to reside on objective, rational facts. In reality, deciding where to live is very subjective, and people rely strongly on emotions and their feeling of well-being to justify their choice. How can these subjective features be quantified and included in a computational model? And what can be expected of the results? It turns out that the way residents respond to otherness, whether they enjoy being subjected to people from other social strata or not, is a key factor in the evolution of urban space.

From Agents to Actors

City traffic networks, ant hills, and the immune system are just three examples of dynamic complex systems that are the result of the interactions between very large numbers of individual entities, here cars, ants, or immune cells. Such complex systems have been studied computationally using a modeling approach called Agent Based Modeling (ABM). First, each individual entity (e.g. each ant) is given a set of rules that dictates how it will respond to its environment. Then a large number of such entities are brought together on a map that represents the external constraints they are subject to. Finally the computer simulation is started, and the individual cars, ants, or immune cells are let loose, allowed to interact, thereby allowing the system as a whole to evolve.

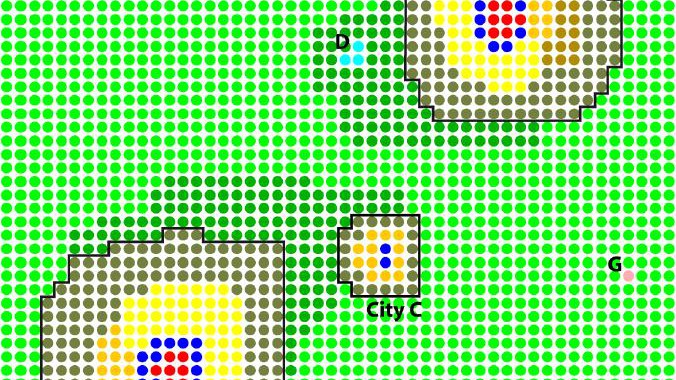

In their publication, entitled “The city they want, the city they make” (La ville qu'ils veulent, la ville qu'ils font, Revue Urbanisme, No. 238), Prof. Lévy and Dr. Ourednik base themselves on an agent based model to study the evolution of an urbanized environment. They let about one and a half million virtual residents loose on a terrain mimicking the western, French speaking part of Switzerland. Two major cities are represented, as well as two towns and a ski-resort. Each city is composed of different urban types, characterized by their functional diversity, their accessibility, their housing prices, the infrastructure, their population, and their social class, based on real data drawn from statistics. Surrounding the city center lie the wealthy residential areas, the middle class suburbs, the lower class suburbs, and so on. Throughout the simulation, the families are offered to relocate within the entire region, and depending on how they score each choice, they either decide to move or to stay put.

In their evaluation of current and potential neighborhoods, virtual residents draw not only on the raw facts distinguishing the options, but also on their perception of each neighborhood. This perception is considered to depend on one critical personally trait: whether they feel attracted to or repelled from “otherness”. Allophiles, those attracted to "otherness" are eager to live in suburbs with a high level of social mixing. By contrast, allophobes are put off by this idea and would rather live amongst people of (at least) their own social standing. The rational entities are thus endowed with a degree of personality and go from being simple agents to being actors.

A healthy city

Many of the results of the study confirm intuitive expectations, but a few almost counter-intuitive results stand out. As expected, an allophilic population will give rise to a city with a higher degree of mixing, with the wealthy living side by side with the less well to do. Subsidizing families with children will further increase this mixing by lowering the financial burden of living downtown. Gentrification, the process by which popular neighborhoods go from being hip to bourgeois, can be avoided by a public policy which helps families move to neighborhoods that would otherwise be financially inaccessible to them. In a population of allophiles, public policy can help achieve the goal of a dense, diverse city center.

As expected, predominantly allophobic populations will tend to fragment into neighborhoods with low levels of social mixing, strongly populating the suburbs. In this case, subsidies appear to further increase the flight of the wealthy from the city center to the suburbs. With city centers more affordable for the less well-to-do, they become more diverse, and thus less popular to the affluent allophobes. If a healthy city is defined as one with a densely populated, active center, it seems like there is only so much public policy can do if the majority of the population share an allophobic attitude. Attitude, it seems, is a dominant force in directing the development of an urban area, perhaps more so than its infrastructure, its institutions, or its residents' income levels.