Questioning our relationship with technology through aesthetics

© 2024 EPFL

Léa Pereyre, an artist trained in Industrial Design at ECAL, joined MOBOTS two years ago with the aim of developing a new approach to educational robotics based on aesthetics.

In this interview, she reflects on a journey that weaves through scientific labs, workshops and exhibition venues, exploring our digitized society in a poetic and moving way.

Can you tell us a little about your early career?

I did my Bachelor's degree at ECAL, specializing in Industrial and Product Design. There you learn how to design objects, from conceptualization to industrialization. It’s a good setting to try your hand at many things and learn a bit about everything; to get to know machines, to do a lot of manual work. We're encouraged to discover other trades, to collaborate with craftsmen and women as well as engineers. It was an experience I particularly enjoyed and one that motivated me to approach Francesco Mondada here at EPFL after my Bachelor's degree.

What was the starting point of your interest in engineering?

During my degree, we had the opportunity to collaborate with students from the Media Interaction Design section. Unlike industrial design, this section encourages the use of new technologies while maintaining a creative approach and a strong visual emphasis. As part of this joint project, we were asked to imagine connected objects for a futuristic home, addressed in an absurd and humorous way. This project, entitled Delirious Home, was a great success, and in 2014 it was presented at Milan Design Week in the form of an apartment entirely furnished with these connected objects, reacting in unexpected ways to visitors.

With two members of my project group, we designed a giant clock which, instead of simply displaying time, stopped showing it as soon as someone walked past to instead mirror the visitor's movements, transforming one’s relationship to time. The idea was to turn the race against the clock on its head and invite visitors to pause and play with time.

I've always been fascinated by objects in motion, by the phenomenon of organical evolution and transformation. This project acted as a trigger: it made me want to explore further the emotional potential of robotically animated objects. I did hesitate for a while between deepening my technical skills or collaborating with experts in the field. In the end, I chose the path of collaboration. My less technical designer's eye brought a creative naivety that offered a different perspective from that of an engineer, making for a rich human exchange.

After graduating, I took up an internship at the LSRO at the time - the Robotic Systems Laboratory at EPFL - it was through a grant that Francesco had to collaborate with designers to develop creative activities with the Thymio robot. He took me on as an intern for six months, and it was thanks to this first opportunity in robotics that all the other doors opened.

In your current role within MOBOTS, you're working on a project entitled “The Beauty and the Machine: Joining Aesthetics and Robotics in Education”, which explores an aesthetic approach to educational robotics. Can you tell us more about this?

In this research project, we aim to propose a poetic and sensitive vision of the robotic tool. Through this approach, we want to understand whether it's possible to change the sometimes negative or overly technical perception of robotics in the educational context.

Where does the project stand now?

2024 was all about experimentation: understanding what possibilities lie ahead, while leaving ourselves room for error. We began by experimenting with future teachers in the context of programming activities, either with one of our aesthetic explorations, or without. In the end, the approach was so decontextualized that it didn't give us what we wanted.

But we did learn a lot: how to communicate our creative vision, how to create stimulating and affordable content for future teachers to motivate them to appropriate and integrate this vision into their classrooms.

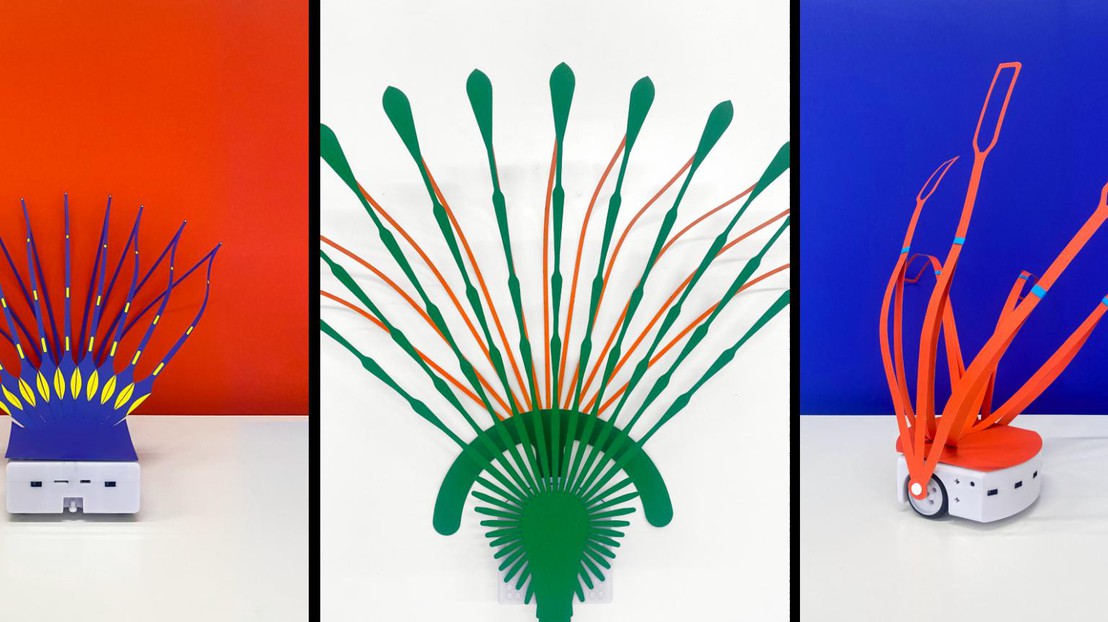

Part of our work with Manuel Bernal Lecina is to supervise semester projects in which EPFL students are encouraged to explore some form of creativity, whether in programming or through physical realizations. They are involved in the development of the Beauty and the Machine project. One student, for example, developed programs for the costumes, and was invited to explore her own creativity from a programming standpoint. Joël Coelho Oliveira, for his part, is currently developing a new robot, the Sthymuli, with Alejandrina Hernandez Zavarce who is also from ECAL.

In all these different activities, robotics is used as a creative tool. Technology is no longer an end in itself, but is used to support the poetic, the sensitive and the tangible.

Aside from your work at EPFL, you have other projects as a designer, can you tell us about them?

What's going on at EPFL is very compatible and always linked to my freelance work. Each year, with my colleague Claire Pondard, whom I met during my studies, we develop new projects that question the relationship between humans and the digital world.

In the same vein, our robotic sculptures question the aesthetics of robotics in society. With the democratization of these tools, we have an opportunity to take a look at the aesthetics and behavior of these animated objects. We want to propose a vision of robotics that doesn't just appeal to efficiency, but also to the world that is specific to us as humans, which is more in the realm of sensitivity, nuance and poetry.

As designers, we have a particular responsibility in a society increasingly shaped by digital technology. While one part of the population adapts easily, another encounters difficulties. Today's technical world imposes a sleek, minimalist aesthetic, where objects become miniaturized and tend to disappear. Yet a material dimension essential to human existence persists and deserves to be preserved.

The aim is to provoke reflection through projects presented to a wide audience, and to draw attention to the technical field. This year, for example, we developed a project involving an industrial robotic arm, exhibited at Milan Design Week. This collaborative arm, designed to assist workers through simple programming, was staged in an organic choreography. Taken out of its usual industrial context, it captivated an audience often discovering it for the first time. Visitors were able to get close to it and touch it, eliciting a variety of emotional reactions. It begs the question: why do these “inanimate” objects provoke fear, fascination or amusement in us?

This approach can also be adapted to the world of object design, notably through a project on the emotional legacy of our data. We realized that, unlike our grandparents who left behind photo albums, vinyl records or letters, our future generations are likely to leave behind only a computer, a password, USB sticks and hard drives - objects devoid of any sensitivity. As an answer to this, we collaborated with the Sèvres manufactory in Paris to create a series of vases. These vases, adorned with gold leaf forming QR codes, provide access to an online storage space. This statement project proposes to collect precious memories such as photos and videos throughout one's life, in order to give a tangible dimension to this emotional heritage through an object.

Find out more about Léa Pereyre and the Robotics and Design project.