“Our job is to put pencils back in students' hands”

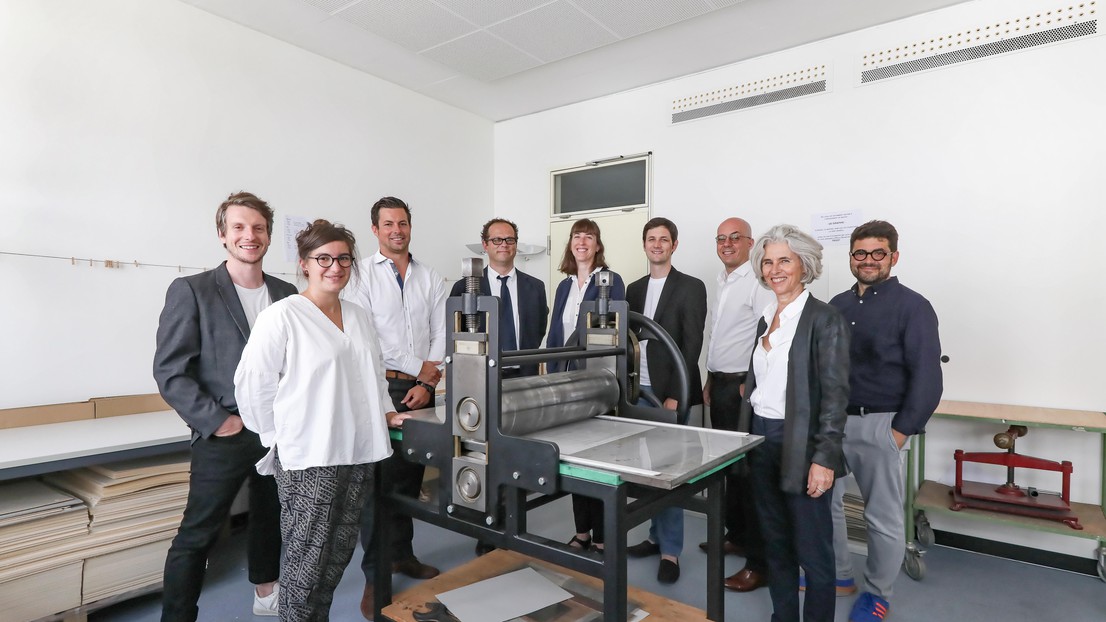

The team at the Arts of Sciences Laboratory © Alain Herzog 2020 EPFL (picture taken before the rule to wear a mask)

The team of teachers at the Arts of Sciences Laboratory (LAPIS) has won the best teaching award for the architecture section. Here’s a look at the scientist, lecturer, Paule Soubeyrand and her team.

(The main picture was taken before the rules for face masks.)

Twenty-six years after joining EPFL, Paule Soubeyrand has now been recognized for her work as a teacher. She had never heard of the best-teacher award until now. And although the award goes to all the LAPIS teachers – two of whom are new this year and honored to already have been recognized – they unanimously congratulate Soubeyrand for “everything she’s set up over the years. Paule has woven together her teaching approach over the years like a tightly-knit fabric,” says Emy Amstein, who’s been working with Soubeyrand for 15 years.

Soubeyrand’s team is made up of seven architects and a graphic designer, each of whom also has a private practice. The teachers are divided into teaching pairs that are mixed in terms of gender and years of experience. It’s a well-oiled team that is satisfied with its leadership. “The key is to get the course content right, which is exactly what Paule and Emy have done. That leaves us free to focus on the best way to teach the material and lets us hit the ground running. Everyone at the lab works well together. It’s an easy and great team to be part of,” say Victoire Paternault and Luis Perrier. “The small class size makes it easier to be creative, and students feel more comfortable speaking up,” says Loïc Jacot-Guillarmod. Bérénice Pinon adds: “We have good course materials that detail precisely what we should cover in our classes. And by teaching in pairs, we’re able to have more relaxed, informal discussions with students. It’s a method that works really well – and that’s reflected in the assignments our students hand in.”

Learning by doing

The workload for LAPIS students is considerable – each semester they must complete at least ten exercises involving expression, geometry, projections, and more. This is intended to expose students to a variety of fields so they can decide which they like best. The one thing all exercises have in common is drawing, whether done with fingers in the sand – its most basic form – or using more sophisticated instruments.

When we teach, we should start with techniques for drawing by hand so that students learn to connect ideas in their head with the movement of a pencil. Some students are even surprised to learn that you can do anything by hand that you can do on the computer.

One might think that art students would never leave home without a pencil and sketchbook, but that’s no longer the case. “Surprisingly, many students come to class without paper and pencil,” says Paternault. “They feel increasingly uncomfortable with instruments that aren’t digital. Drawing by hand should be instinctive and natural – but for many of them it’s an arduous task. Some students are even afraid they won’t be able to produce a decent sketch on the first try.” Soubeyrand and Delphine Passaquay agree with her: “Students have become so used to drawing on their computers that their hands have lost that spatial sense. Now that tablets have replaced children’s drawing and coloring books, students no longer have the feeling of pencil moving across paper. We still don’t know the full ramifications of that shift.” Pinon, only half-jokingly, summarizes the teaching team’s job as “putting pencils back in students’ hands” so that they can try things out and explore.

The reward is the light-bulb moment

Does that mean we should ban computers and only draw by hand? Not at all. Soubeyrand believes there are advantages to both methods. Amstein explains: “We tend to think of pencils and computers as mutually exclusive. But computer-aided design tools have been around for 30 years. Rather, we should think of software programs as an extension of manual drawing tools. After all, these programs are based on the same fundamentals – lines and surfaces. When we teach, we should start with techniques for drawing by hand so that students learn to connect ideas in their head with the movement of a pencil. Some students are even surprised to learn that you can do anything by hand that you can do on the computer.” Granted, this approach takes time, even with modern tools that speed up the process. “It’s like going up a long staircase, you need to take it one step at a time,” says Perrier.

What is it that motivates the LAPIS teachers? “What I enjoy is the interaction with students. In my professional practice I’m alone in front of my computer, so I get a lot out of the class discussions,” says Julia Magnin, LAPIS’s most recent hire. Passaquay agrees: “Speaking with both students and teachers is gratifying because it gives you a nice balance. We discuss different teaching methods and topics to cover, which improves how I give my classes.” The reward for teachers is when they see the light bulb go off in students’ heads. In other words, when their bright ideas come to life in their drawings.