MRI helps unravel the mysteries of sleep

Scientists at EPFL and the Universities of Geneva, Cape Town and Bochum have joined forces to investigate brain activity during sleep with the help of MRI scans. It turns out our brains are much more active than we thought.

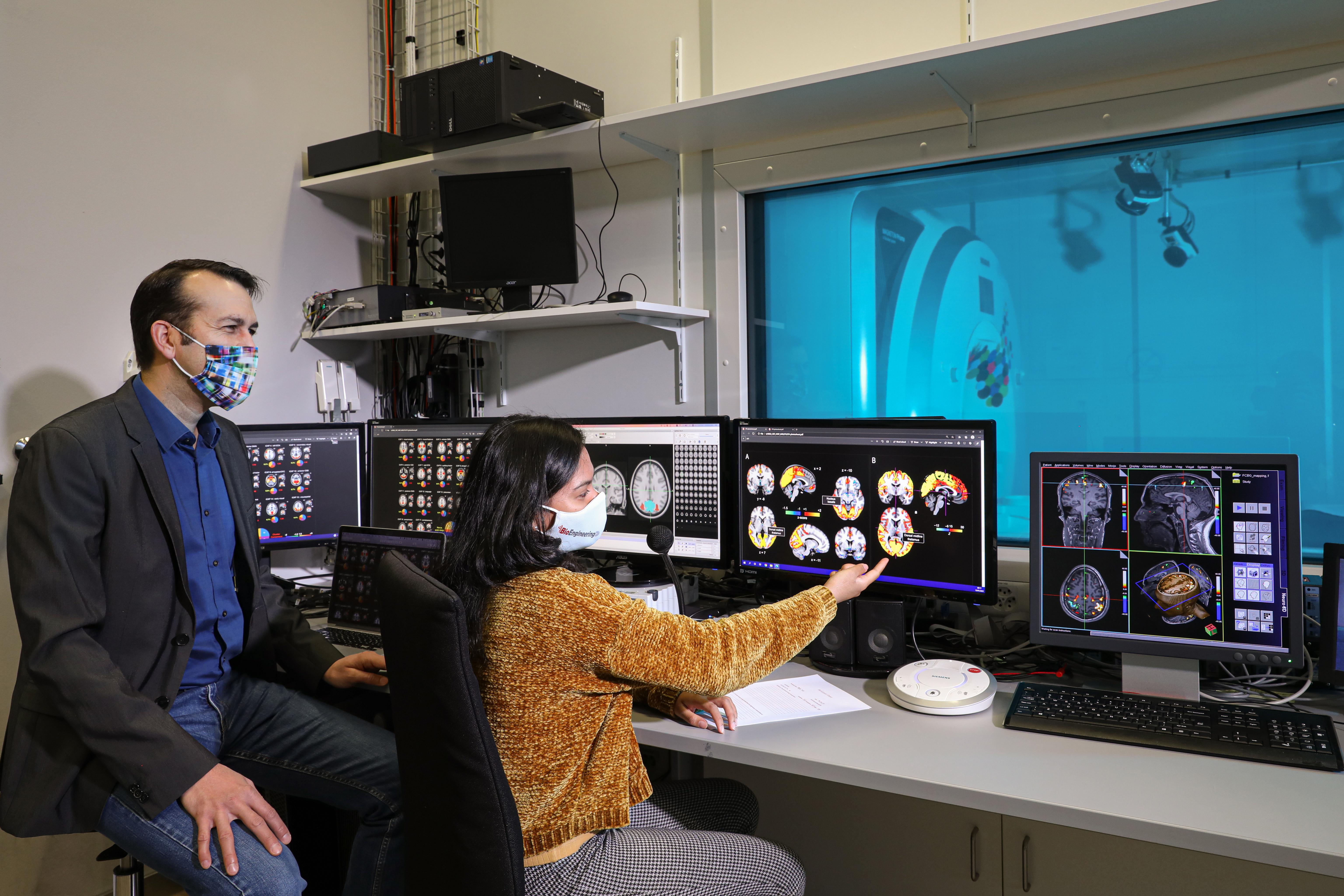

Our state of consciousness changes significantly during stages of deep sleep, just as it does in a coma or under general anesthesia. Scientists have long believed – but couldn’t be certain – that brain activity declines when we sleep. Most research on sleep is conducted using electroencephalography (EEG), a method that entails measuring brain activity through electrodes placed along a patient’s scalp. However, Anjali Tarun, a doctoral assistant at EPFL’s Medical Image Processing Laboratory within the School of Engineering, decided to investigate brain activity during sleep using magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. According to Dimitri Van De Ville, who heads the lab, “MRI scans measure neural activity by detecting the hemodynamic response of structures throughout the brain, thereby providing important information in addition to EEGs.” During these experiments, Tarun relied upon EEG to identify when the study participants had fallen asleep and pinpoint the different stages of sleep. Then she examined the MRI images to generate spatial maps of neural activity and determine different brain states.

Difficult data to obtain

The only catch was that it wasn’t easy to perform brain MRIs on participants while they were sleeping. The machines are very noisy, making it hard for participants to reach a state of deep sleep. But working with Prof. Sophie Schwartz at the University of Geneva and Prof. Nikolai Axmacher at Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Tarun could leverage simultaneous MRI and EEG data from around thirty people. The brain-activity data were covered a period of nearly two hours while participants were sleeping in an MRI machine. “Two hours is a relatively long time, meaning we were able to obtain a set of rare, reliable data,” says Tarun. “MRIs carried out while a patient is performing a cognitive task usually last around 10–30 minutes.”

Brain activity during sleep

After checking, analyzing and comparing all the data, what Tarun found was surprising. “We calculated exactly how many times networks made up of different parts of the brain became active during each stage of sleep,” she says. “We discovered that during light stages of sleep – that is, between when you fall asleep and when you enter a state of deep sleep – overall brain activity decreases. But communication among different parts of the brain becomes much more dynamic. We think that’s due to the instability of brain states during this phase.” Van De Ville adds: “What really surprised us in all this was the resulting paradox. During the transition phase from light to deep sleep, local brain activity increased and mutual interaction decreased. This indicates the inability of brain networks to synchronize.”

The role of default-mode networks and the cerebellum

Consciousness is generally associated with neural networks that may be linked to our introspection processes, episodic memory and spontaneous thought. “We saw that the network between the anterior and posterior regions broke down, and this became increasingly pronounced with increasing sleep depth,” says Van De Ville. “A similar breakdown in neural networks was also observed in the cerebellum, which is typically associated with motor control.” For now, the scientists don’t know exactly why this happens. But their findings are a first step towards a better understanding of our state of consciousness while we sleep. “Our findings show that consciousness is the result of interactions between different brain regions, and not in localized brain activity,” says Tarun. “By studying how our state of consciousness is altered during different stages of sleep, and what that means in terms of brain network activity, we can better understand and account for the wide range of brain functions that characterize us as human beings.”

A.T. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under the Project Grant 205321-163376. D.W.A is supported by the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS) under the Project Grant SDS14/1117, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) Grant 91570813, the National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF) Grant 83341, and the Harry Oppenheimer Memorial Trust, South Africa Grant OMT 20027. This work was supported by the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) Affective Sciences financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number: 51NF40-104897) and hosted by the University of Geneva, and by individual grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (to S.S., grant numbers: 320030-159862 and 320030-135653), and by the Mercier Foundation. Study 1 was conducted on the imaging platform at the Brain and Behavior Lab (BBL) and benefited from support of the BBL technical staff.