“Mediocre tools lead to mediocre thinking”

Bernard Tschumi in the offices of EPFL’s Modern Architecture Archives. ©Murielle Gerber/EPFL 2018

Architect Bernard Tschumi has donated the archives of his Bridge City project – developed for the City of Lausanne in 1988 – to EPFL. We spoke with Tschumi about the important lessons these documents contain, while he was at EPFL for a talk on 11 October.

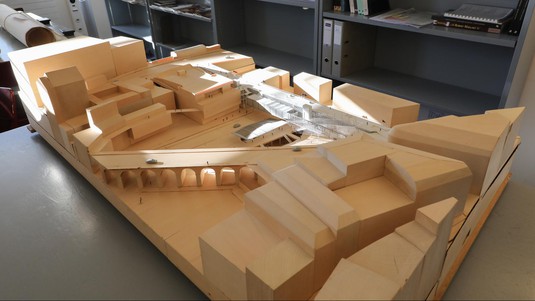

The Bridge City project archives – comprising five models, twelve rolls of plans and dozens of drawings, photographs and files – have just been transferred from New York to their new home at EPFL’s Modern Architecture Archives (ACM). New York-based architect Bernard Tschumi donated the archives to ACM, where they will join those of his father Jean Tschumi, founder of the Lausanne School of Architecture and the architect behind Swiss insurer Vaudoise’s headquarters in Lausanne, the World Health Organization’s buildings in Geneva and Nestlé’s headquarters in Vevey.

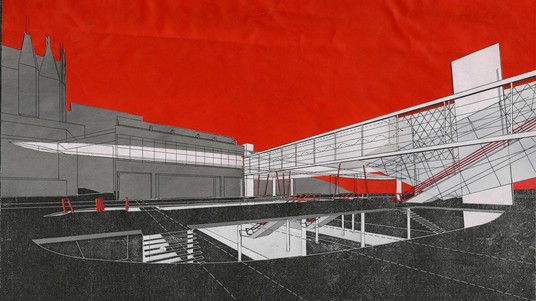

The Bridge City designs were commissioned by the City of Lausanne in 1988 and were developed jointly by Bernard Tschumi and fellow architect Luca Merlini. Their concept won the City’s request for proposals to redevelop the Flon district, which was then an abandoned industrial zone. Their idea was to build four inhabited bridges between Chauderon Bridge and where Place de l’Europe is currently, in order to link the two sides of the Flon river valley. They also planned to demolish all but four of the industrial warehouses and create a park at the southern end of the site, on the slopes of Montbenon.

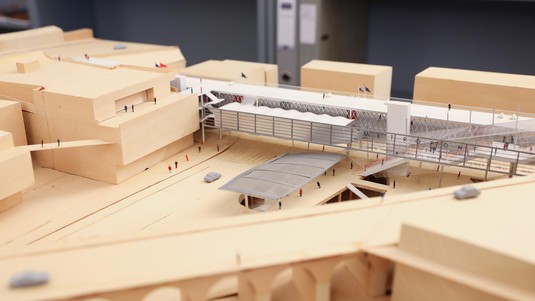

The bridges would hold residences, shops, a theater, a museum and an auditorium for the University of Lausanne and the Lausanne University of Art and Design (ECAL). Diagonal stairways and ramps would provide passageways between the upper and lower areas.

But none of that happened. The designs spent eight years collecting dust in the city hall, as urban planners faced opposition from the property’s owners – LO Holding – as well as a coalition of the right, green and workers’ parties. The Bridge City project was eventually abandoned. Instead, Tschumi and Merlini, along with architect Emmanuel Ventura, built only the Flon interface, which included a pedestrian bridge, Place de l’Europe, the Flon metro station and the LEB station, and was opened in 2001. LO Holding developed the rest of the Flon district on its own.

Tschumi, a dual French-Swiss citizen, is today a prominent figure in the global architecture community. He spoke to a packed room at EPFL on 11 October as part of Archizoom’s Isle of Models exhibition. We sat down with him for a look back – and ahead – at his field.

Thirty years on, what lessons can EPFL students and researchers learn from the Bridge City archives?

There were two aspects to our Bridge City project. The first was architectural and urbanistic in the conceptual sense – we aimed to understand how a site’s characteristics can lead to an abstract idea. And how we can then transform this idea so it becomes an integral part of the site itself. The Flon valley’s topography suggested an approach that was at once architectural and urbanistic. We no longer saw any distinction between the two; the concept and the context blended together. The second aspect concerned versatility. We wanted to transform bridges into places where people can also live, study and shop. We weren’t the first ones to come up with the idea of turning infrastructure into architecture – just look at Ponte Vecchio in Florence. This approach could interest researchers today, especially since – as far as architecture is concerned – culture and usage haven’t changed much from one century to the next. Architects in the 15th and 21st centuries face largely the same challenges because we still work in three dimensions, we work with mostly similar materials and we work on the scale of the human being.

What do you think of the Flon district as it stands today?

I’ve always felt that our Bridge City project was a missed opportunity. The way the Flon river valley has been developed doesn’t take advantage of Lausanne’s topography. The district currently has a lower part, in the bottom of the valley, and an upper part. But the diagonal – passing from the lower to the upper part – is completely ignored. However, Lausanne is one of the world’s few 3D cities – like Metropolis in the film by Fritz Lang. If you look at drawings by Futurist Italian architect Antonio Sant'Elia [b. 1888, d. 1916], where he imagined a vast network of bridges – that’s Lausanne. I know of no other city with such a high density of bridges. Bridges in Lausanne have an urbanistic function; they are not solely infrastructure. The inhabited bridges in our Bridge City project would have been arteries connecting the upper and lower areas.

Couldn’t high-rise buildings serve this purpose in Lausanne?

High-rise buildings are a cliché, a lazy concept. And there’s no logic behind simply throwing up high-rises arbitrarily. Manhattan has a lot of high-rises because its surface area is small and narrow, because the ground conditions make it possible and because someone was clever enough to invent elevators. But if an architect told me he was going to build a high-rise in Chavannes, I would ask him “Why? What’s the underlying concept?” The smartest high-rise in Lausanne is still the Bel-Air building because it connects the bottom of the Flon valley with the street level above and is cleverly placed at the end of Grand Pont. A 20-story building rising from the river-valley floor up to and above Pont Bessières would also be a good idea.

You were Dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture from 1988 to 2003 and ran your own architecture firm. In both of these roles you showed an interest in digital technology. How do you believe the digital transformation has affected the teaching of architecture and the architecture profession?

When I started as Dean in 1988, I never set out to make Columbia a research center for architecture software. But three or four years later I saw that architects were not using the new modeling programs that were out there – programs to create special effects, like those developed for Jurassic Park (1993), and programs used in biology and fluid mechanics. This also has to do with the idea of versatility. So we started looking at how the new software could be used in more versatile ways and applied to architecture. Here we began blurring the lines between different disciplines. AutoCAD had been around since 1985 but wasn’t very exciting. With the newer software being released at the time we entered into an experimental period. We saw that we could invent new types of spaces and tried to apply them to actual projects. It was an exciting time. But software developers soon began adapting their programs to market demand, making them more “civilized.” Now you can easily build a house or a set of shelves or design a landscape, for example.

Why is this a loss?

Because instead of sparking new ideas, the software mimics reality as it already exists. It creates a kind of hyperrealism that is completely at odds with the experimental mindset I mentioned earlier. And that leads to another problem: today the people commissioning architecture projects want to see images of what the structures will look like, and rather than evaluating designs with their heads, they just take them at face value. They’re interested only in “what it’ll look like.” That means architects have to cater to developers who don’t know how to read a blueprint or a cross-section, or how to comprehend anything abstract. In my view that has done great prejudice to the architecture profession. We can group all these hyperrealistic images into a kind of dictionary of clichés; it’s all become very pedestrian. The tools we use have a big influence on how we think. Mediocre tools lead to mediocre thinking. Today’s architects need to rise above that. Some of the designs for our Bridge City project took abstraction to the extreme. Today our proposal wouldn’t even make it to the shortlist.

How do you fight against this standardization of the profession in your teaching at Columbia?

My colleagues and I try to bring back the system of representation, such as by deforming computer images or not using them at all. We try to force software to do things it wasn’t designed to do, in an effort to move the concept forward in a way that goes beyond hyperrealism.

Key dates

- 25 January 1944: Born in Lausanne to a Swiss father, Jean Tschumi, and a French mother

- 1969: Studied in Paris, London and Zurich; obtained an architecture degree from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich

- 1969–1980: Taught at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London

- 1975: Moved to New York

- 1981 and 1994: Published The Manhattan Transcripts (Academy Editions and St. Martin’s Press

- 1983: Won the contract to design La Villette park in Paris and opened an architecture firm in France

- 1988: Founded Bernard Tschumi Architects (BTA) in New York; won the contract to redevelop the Flon district in Lausanne with his Bridge City concept

- 1988–2003: Served as Dean of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University, New York

- 1994–2010: Published Event-Cities Series (MIT Press)

- 1994: MoMA exhibition Bernard Tschumi: Architecture and Event, New York

- 1997: Fresnoy National Studio for the Contemporary Arts, Tourcoing, France

- 1999: Lerner Hall Student Center, Columbia University, New York

- 1999: Ecole d’architecture de Paris, Marne-la-Vallée

- 2001: Flon interface, Lausanne

- 2001: Zénith concert hall in Rouen, France

- 2003: Florida International University’s School of Architecture, Miami

- 2002: Founded Bernard Tschumi urbanistes Architectes (BTuA) in Paris

- 2004: Vacheron Constantin Headquarters and Manufacturing Center, Geneva

- 2007: Richard E. Lindner Athletics Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

- 2007: Zénith concert hall in Limoges, France

- 2007: BLUE Tower (aka Blue Condominium), New York

- 2007: Lausanne University of Art and Design (ECAL), Lausanne

- 2009: Acropolis Museum, Athens

- 2012: Published Architecture Concepts: Red is Not a Color (Rizzoli), New York

- 2012: Alésia Archeological Museum, France

- 2014: Vincennes Zoo, Paris

- 2014: Paul & Henri Carnal Hall, Institut Le Rosey, Rolle, Switzerland

- 2017: Exploratorium Museum of Industry and the City, Tianjin, China