Maintaining the structure of gold and silver in alloys

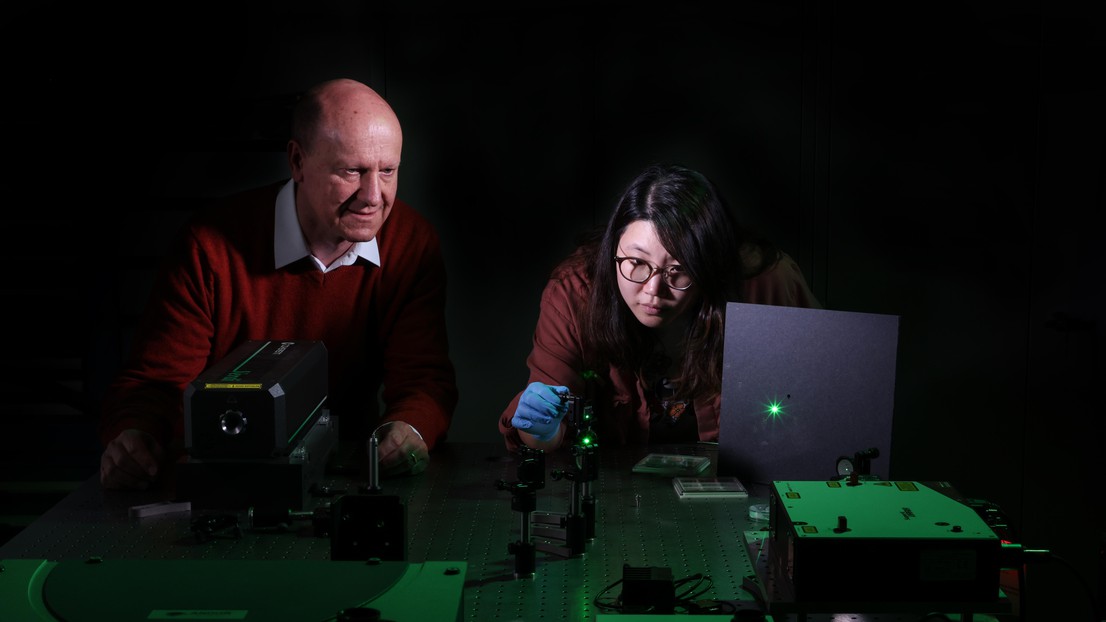

Olivier Martin and Jeonghyeon Kim work with the laser whose power has been reduced to the level corresponding to class 1. 2022 EPFL/ Alain Herzog- CC-BY-SA 4.0

EPFL engineers have developed a low-temperature annealing method that maintains the structure of gold and silver when the two metals are combined in an alloy. Their discovery will prove useful in the manufacture of contact lenses, holographic optical elements and other optical components, since the new alloys reflect the full spectral range.

Gold, silver, copper and aluminum are widely used in the manufacture of optical components because of their reflective properties. Gold, for instance, reflects red light, while silver reflects blue light. These metals are also of interest to scientists, who study them at the nanoscale, since nanostructures have a completely different optical response than bulk materials. At this scale, light interacts differently than it would with the same metal in a larger quantity, such as in a gold bar. Engineers at the Nanophotonics and Metrology Laboratory (NAM), part of EPFL’s School of Engineering (STI), set themselves a challenge: to develop a material that reflects every color in the spectrum.

Combining the optical effects of both metals

“We realized that, by creating an alloy of gold and silver, we could combine the optical effects of both metals in a single material,” says Professor Olivier Martin, who heads the laboratory. Conventional gold and silver alloys are fabricated at the high temperatures of 800–1,000°C. But this process alters the form of the nanostructures. “Current annealing methods don’t maintain the structure of the two metals,” explains Martin. To get around this problem, the engineers set about developing a low-temperature annealing method that would work for any alloy mixture.

300 degrees Celsius

In the lab, Martin’s team first demonstrated the feasibility of using a low-temperature annealing method to fabricate a gold and silver alloy. The engineers heated both metals to 300°C for eight hours, and then to 450° for a further 30 minutes, successfully producing an alloyed gold-silver thin film. “We use nanoscale layers in our process,” says Jeonghyeon Kim, a PhD student and member of the team. “They’re incredibly thin.” The engineers discovered that their method maintains the structures of the two metals – and that the new material reflects the full spectral range, depending on its composition. “Low-temperature annealing produces well-alloyed materials but doesn’t alter the form of the particles. It’s as if we’ve combined the optical properties of gold and silver. Our alloy reflects new colors.”

The research team also experimented with different alloy ratios. “The optical effects change as we add more gold or silver to the mixture,” says Martin. Their method, which could be used to manufacture new optical instruments, also has more everyday applications. “Our material could find its way onto watch and clock dials, for instance,” adds Martin.

European Research Council (No. ERC-2015-AdG-695206 Nanofactory)

Swiss National Science Foundation (Project No. 200021_162453)