“I'd call my teaching style ‘old school-plus'”

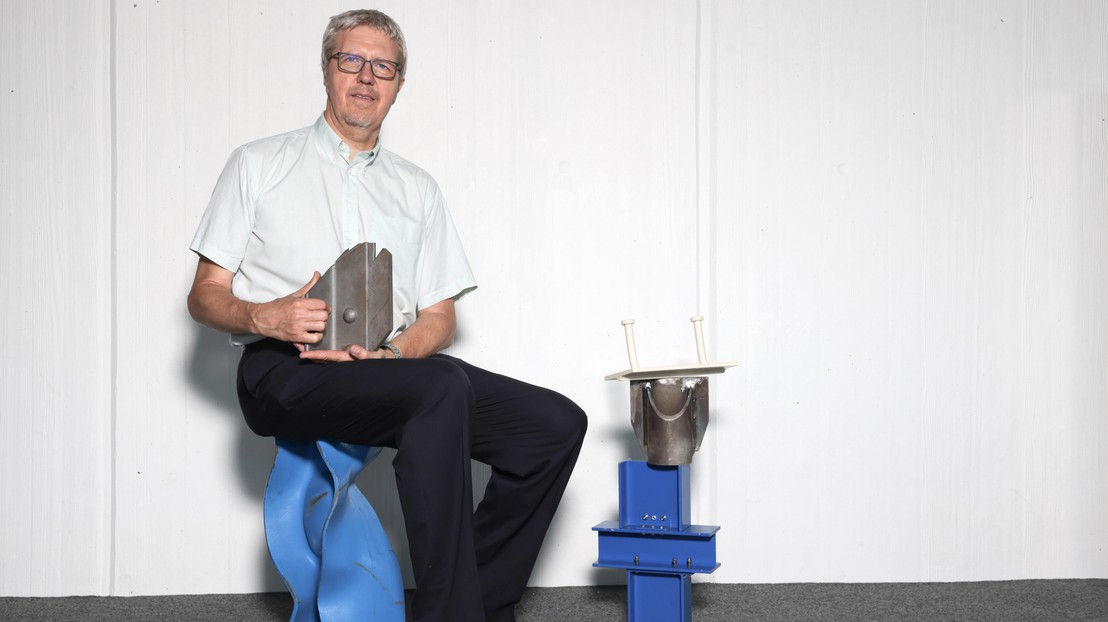

Alain Nussbaumer © 2024 EPFL/Alain Herzog - CC-BY-SA 4.0

Alain Nussbaumer, voted best teacher in the civil engineering section for 2024, could very well have studied mechanical engineering and gone into the aerospace or shipbuilding industry. Because what he’s really excited about are structures of all shapes and sizes.

One foot on the ground, one foot in the water, eyes fixed on the sky. Alain Nussbaumer could have easily pursued a career in aerospace or shipbuilding – he stumbled into civil engineering almost by accident. Yet this was a fortuitous career choice, as it took him to the US, France and back to EPFL, where he’s now a full professor at the Resilient Steel Structures Laboratory (RESSLab). There, his research group is studying the fatigue and rupture mechanisms of steel structures such as road bridges.

“When you get down to it, there’s not much difference between an airplane’s wings, a ship’s hull and a viaduct – at least from the perspective of their load-bearing structures,” says Nussbaumer. He’s been called on to serve as an expert on ambitious international, cross-disciplinary projects in all these areas; past projects include the Millau Viaduct, the Alinghi sailboat and the Solar Impulse aircraft. And the day after this interview, Nussbaumer was scheduled to give a talk at the Pilatus Aircraft headquarters in Stans, Switzerland.

Construction toys

“You’ve probably figured out by now that what I’m really interested in is structures, perhaps even more so than civil engineering,” he says. “I like finding the best way to distribute a load across a structure and pulling together concepts and methods from an array of disciplines.” Nussbaumer’s interest in structures runs in the family: “My grandfather ran a civil engineering firm and worked on large roadway construction projects in the 1960s and 70s.” Nussbaumer’s father often bought him construction toys such as Legos, and was always ready to roll up his sleeves – and sometimes his trouser cuffs – “to help me build miniature dams on nearby streams.”

As an adult, Nussbaumer hasn’t entirely given up his toys. During our interview, he digs around in his desk and produces an object that resembles a modular construction toy made of metal and containing a base, several magnetic springs and tiny balls. “I made this using a Mola structural kit,” he explains. “The Mola system was developed by a university student in Brazil. It’s designed to help teach the principles of structural engineering and show how important things like stability and deformation are. It’s really useful for demonstrating the forces affecting structures and the rules for how they should be built.”

Nussbaumer, who himself enrolled at EPFL exactly 40 years ago, is particularly motivated by the goal of “helping students understand the theory behind the mathematical formulas they’ll be using in their careers.” After spending so much time delving deep into complicated subjects and highly sophisticated concepts, civil engineering students sometimes lose sight of the essence of their profession: “Designing safe, fit-for-purpose structures that will last as long as possible.”

A role that’s at once simple and complex

Nussbaumer uses a teaching style that he jokingly describes as “old school-plus.” His lectures come with no bells or whistles, perhaps some animated PowerPoint slides – “but that’s all!” he says. He likes to include a lot of informal discussion in his classes when they’re not too big. “I know this makes it harder for timid students to participate. To help them speak up, I try to break the ice as early in the semester as possible, such as by actively taking part in the exercise sessions.”

Nussbaumer sees his role as a teacher as both “very simple” and “very complex.” It entails introducing students to concrete applications of things they learned in the basic sciences, like physics and chemistry. “I’m usually the first one to give them a class on structures,” he says. “It’s not easy for them to accept that there’s never just one solution to a problem.” He admits that this sometimes poses challenges for him, too. “If I give an exam question that’s too open, grading it can be a real headache!”

Teaching them to ask the right questions

Nussbaumer, like many professors in other EPFL departments, has noticed that today’s students are particularly attuned to the issue of sustainability. “There are no ready-made solutions in the construction industry,” he says. “It all depends on where on the planet a given site is.” In developed countries, the priority in terms of sustainable construction is to “maintain existing buildings so as to limit the use of resources.” But in the developing world, engineers must often construct new buildings and “replace existing ones, if they’re in poor shape, to achieve greater resilience and sustainability.”

It's therefore impossible to teach students sustainable construction per se at an internationally oriented university like EPFL. “What we can do, however, is teach them to ask the right questions.”