How organic architecture can shape dense, diverse cityscapes

In a new book, researchers from EPFL examine the history of organic architecture, complete with telling examples of the genre, from its emergence in the early 20th century to the present day. They observe that the movement is enjoying a revival – particularly in Switzerland – that’s being driven by the demands of high-density urban development.

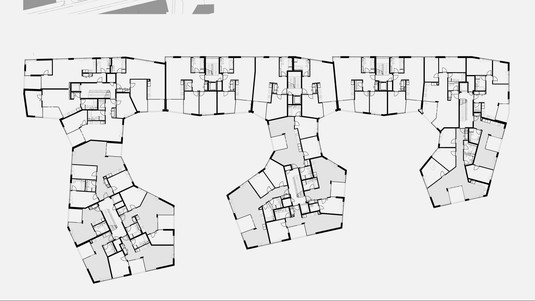

Rooms with curved corners. Buildings constructed at angles so apartments aren’t face to face. Outdoor spaces arranged into small, planted alcoves rather than large, rectangular playgrounds. Triangular and curved balconies. Apartments of different shapes and sizes occupying the same floor. These are just some of the features of organic architecture, a movement that has given rise to buildings instantly recognizable from the outside for their irregular design and from the inside for their rooms that eschew the conventional rectangle.

In a new book entitled Organique. L’architecture du logement, des écrits aux œuvres (EPFL Press), Christophe Joud and Bruno Marchand, architects and researchers at EPFL’s Theory and History of Architecture Laboratory 2 (LTH2), delve into the fascinating story behind this school of thought, from its birth at the turn of the last century to the present day.

Joud and Marchand focus their attention on residential apartment buildings, taking a fresh look at one of the biggest challenges of modern cities through the prism of history. The first part of the book reflects on works by some of the leading names of the movement, from its American figurehead Frank Lloyd Wright to Finnish architect Alvar Aalto and German pair Hugo Häring and Hans Scharoun.

In part two, the authors show how organic architecture has enjoyed something of a revival since the 2000s, particularly in Switzerland – an assertion they support through interviews with contemporary architects. With their irregular and rounded forms, these organic buildings fit seamlessly into today’s densely packed cityscapes and offer spaces of varying sizes and cleverly designed communal areas, all the while avoiding face-to-face apartments.

Spanning a considerable period of history, the book is an invaluable primer on the theory of housing and the thinking behind this movement and should be of interest to both architecture enthusiasts and contemporary architects seeking inspiration for their projects. Here, we talk to Christophe Joud about the background to this work.

In the early days of the movement, which school of thought did proponents of organic architecture reject?

Frank Lloyd Wright is credited with coining the term “organic architecture,” which he first used in a lecture in 1908. For Wright, it meant designing buildings and structures that are balanced with nature, that grow outward from the inside, and that are tailored to the human functions they serve. The tree is a leitmotif that we see time and again in his works. Organic architects believe that the way a building looks on the outside should be determined by what happens inside, such as how occupants move around the space. That’s why most buildings designed with this philosophy in mind are irregular rather than uniform in appearance. In that sense, the organic school of thought emerged in opposition to the mechanicist, logical and geometric designs that prevailed at the time – and in particular to the modernist and rationalist movement of the 1920s and 1930s, spearheaded by names like Le Corbusier. More specifically, organic architects rejected the efficiency and standardization that characterized mass house-building projects in inter-war Europe.

How did organic architecture evolve in the 20th century?

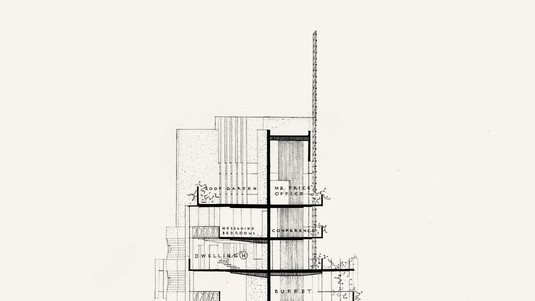

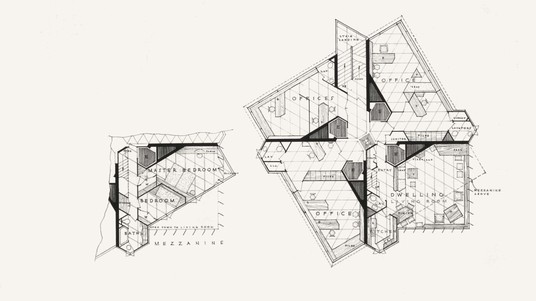

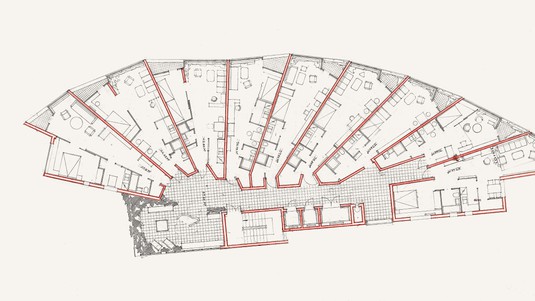

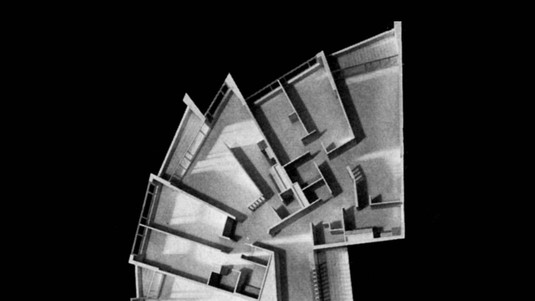

Its popularity ebbed and flowed. It came to prominence in the inter-war period, was mainly limited to the drawing board during the Second World War, and enjoyed its heyday in the post-war era, between the 1940s and the 1960s. In our book, for example, we dig into the personal archives of German architects Hugo Häring and Hans Scharoun – the two men tasked with rebuilding parts of Berlin – to shine a light on some of their iconic works. We also look at the Price Tower in Oklahoma, built in 1956 to a design by Wright. The building is inspired by the form of a tree, with the trunk accommodating service-type activities and the residential parts fanning out from the center like branches. We then examine Scharoun’s Romeo and Juliet apartment building in Stuttgart, built in 1959, revealing the bold and visionary thinking behind its design, with apartments of varying sizes and furnishings selected with intimacy in mind. Its concave and convex facade serves two purposes: it gives residents unique perspectives, and it serves as a clear demarcation between the communal areas and private spaces. Turning to Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, we examine two fan-shaped apartment buildings – one in Bremen, completed in 1962, and another in Lucerne, built in 1968 – both of which are designed to provide expansive views and capture as much sunlight as possible. As we show in our book, these major figures in organic architecture shared much the same vision, albeit at different points in the 20th century.

You note that organic architecture has made something of a comeback in Switzerland since the 2000s. What’s prompted this revival?

The growing popularity of architecture competitions since the 2000s, coupled with today’s increasingly dense cityscapes, has undoubtedly pushed practitioners to trial bolder, more experimental designs. Yet even as recently as two decades ago, apartment buildings were still uniform on the inside despite maybe some contextual differences. But as scarcer land has forced developers to build upward rather than outward, and as our lifestyles have changed and people have begun looking for different types of housing, architects have been forced to adopt hybrid designs and incorporate certain organic features into their thinking. One thing we’ve noticed is a shift in the configuration of internal spaces. Architects have come to realize that by embracing anomalies and unconventional forms they’re able to tailor buildings to different cityscapes and use the space available to them more creatively – for instance by designing folding facades to capture different perspectives or provide space for a desk in a recess. One of the contemporary projects we explore in our book is a 2011 comb-shaped building with irregular teeth, designed by von Ballmoos Krucker, on Badenerstrasse in Zurich. Despite sitting on a narrow strip of land, the clever design means that none of the apartments directly face one another.

Why might contemporary architects find your book useful?

Our book is the first scholarly review of organic architecture projects past and present, so in that sense it fills a gap in the literature on housing. We hope that, by examining the works of early pioneers and more recent innovators, it will help contemporary architects shape new cityscapes, overcome the challenges of high-density urban development, and bring nature back into the city. It’s always fascinating to observe how organic buildings interact positively with the surrounding landscape, vegetation and environment.