How mitochondria make the cut

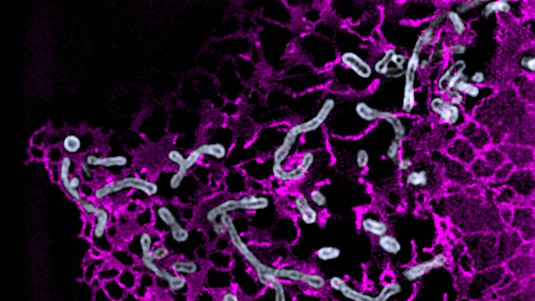

© 2021 EPFL

With the help of their custom-built super-resolution microscope, EPFL biophysicists have discovered where and why mitochondria divide, putting to rest controversy about the underlying molecular machinery of mitochondrial fission. Mitochondria either split in half or cut off their ends to self-regulate. The results are published in Nature.

Mitochondria either split in half to multiply within the cell, or cut off their ends to get rid of damaged material. That’s the take-away message from EPFL biophysicists in their latest research investigating mitochondrial fission. It’s a major departure from the classical textbook explanation of the life cycle of this well-known organelle, the powerhouse of the cell. The results are published in Nature.

“Until this study, it was poorly understood how mitochondria decide where and when to divide,” says EPFL biophysicist Suliana Manley and senior author of the study.

The big question : regulating mitochondrial fission

Mitochondrial fission is important for the proliferation of mitochondria, which is fundamental for cellular growth. As a cell gets bigger, and eventually divides, it needs more fuel and therefore more mitochondria. But mitochondria have their own DNA that is separate from the cell’s DNA, so mitochondria have their own life cycle. They can only proliferate by replicating their DNA, and dividing themselves.

The textbook explanation of mitochondrial fission details the protein machinery that cuts the mitochondrion into two daughter mitochondria, leading to proliferation. But there was mounting evidence in the scientific literature that mitochondrial fission was also a way of getting rid of damaged material.

“For me, the big question was how do mitochondria know when to proliferate or when to degrade? How does the cell regulate these two opposing functions of mitochondrial fission?” explains EPFL postdoc Tatjana Kleele and first author of the study.

Four years of research and 2000 mitochondria later, Kleele and Manley found that the splitting location of mitochondria is not at all random.

Nanoscale super-resolution microscopy

Until now, the dynamics of mitochondrial fission sites had never been measured with high precision and in large numbers. But thanks to their own super resolution microscope (iSIM), the EPFL biophysicists were able to observe many individual mitochondria, in living cancer cell lines and mouse cardiomyocytes, as they split into smaller segments.

“The size of a mitochondrion is just around the diffraction limit for light microscopy, making it impossible to study mitochondrial physiology and shape changes at the sub-organelle level. Using a custom built super-resolution microscope, which allows fast imaging with a two-fold increase in resolution, we were able to analyse a large number of mitochondrial divisions,” explains Manley.

From these observations, they could both quantify the position of fission with high precision, and also detect signs of dysfunction in small parts of the organelle with the help of fluorescent biosensors. A low pH within a mitochondrion is a sign that the proton pump necessary for making ATP, energy for the cell, is no longer working optimally. Calcium concentrations provided information about the mitochondria structures.

They observed two types of mitochondrial division: midzone and peripheral. They discovered that midzone division of mitochondria has all of the textbook molecular machinery of fission. In contrast, peripheral division is associated with mitochondrial stress and dysfunction, and the smaller daughter mitochondrion is subsequently degraded.

Next, the biophysicists wanted to know if they could observe the same behavior in heart cells from mice. In collaboration with the laboratory of Thierry Pedrazzini (CHUV), they discovered that mouse heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) can independently regulate those two types of fissions, because they use different proteins and machineries.

When the scientists stimulated the cardiomyocytes to strongly contract with pharmaceuticals, they found that peripheral division rates increase. In other words, when the cardiomyocytes were over-stimulated or stressed, the mitochondria produced tremendous amounts of energy in order for the heart cells to beat quickly. A by-product of this energy production are free radicals, aka reactive oxygen species, known to lead to dysfunction within the cell, including dysfunction of the mitochondria. The peripheral divisions therefore increase to get rid of damaged mitochondria due to the stress.

When the scientists stimulated the cardiomyocytes to proliferate, they indeed noticed more midzone divisions.

“The behavior of mitochondrial fission that we’ve observed in the lab is very likely relevant for all mammalian cells,” says Kleele.

For Manley, this regulation of mitochondrial fission is important for understanding human diseases, such as neurodegeneration and cardiovascular dysfunction, which are both associated with overactive mitochondrial fission. “Therapeutic approaches are rare, since globally targeting mitochondrial fission has many side effects. By identifying proteins which are specifically involved in either biogenesis or degradation, we can now provide more precise targets for pharmacological approaches,” concludes Manley