EPFL students engineer societal solutions in India

Yasmine Benkirane (HEC Lausanne, UNIL) and Andres Engels (EPFL) interview Keerthi C N (SELCO) © Marius Aeberli

Twelve student volunteers, including those from EPFL and the EPFL + ECAL Lab, spent 10 days developing and testing four solutions to everyday challenges facing Bangalore residents as part of the India Switzerland Social Innovation Camp (INSSINC) pilot program. But the fruits of the students’ labor go beyond the prototypes themselves.

The volunteers of the first INSSINC program included four EPFL students in architecture, materials science and engineering, energy management and sustainability, and management of technology and entrepreneurship, as well as three students from the EPFL + ECAL Lab. Students from the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences and HEC Lausanne of the University of Lausanne (UNIL), and the Lausanne School of Art and Design (ecal) also participated.

With their diverse backgrounds, the volunteers formed four groups that each included a designer, an engineer, an economist, and a social scientist. Over the school holiday from February 1-13, each group used a bottom-up design approach to develop and field-test four sustainable prototype solutions to energy and housing challenges in Bangalore – one of India’s fastest-growing cities.

“This first experience in social entrepreneurship altered my perspectives, and creating social impact will have strong priority in my future activities,” says Jelena Dolecek, a master’s student in materials science and engineering at EPFL who worked on the double-layer roof housing project. “The development of solutions was very interesting because our interdisciplinary backgrounds highlighted different problems and thus solution approaches, which gave rise to intense and inspiring discussions.”

HEC Lausanne student Yasmine Benkirane, who worked on the solar mini-kiosk prototype, said: “This experience was by far the most enriching that I’ve had in every respect thanks to a total immersion in Indian culture, intense work on an exciting subject, and unforgettable encounters. We were in the shoes of a social entrepreneur, who identifies needs by going into the field to design a prototype solution. This allowed me to develop a new perspective, and especially “Jugaad” – a term taken from Hindi that means approaching a problem using limited resources in an innovative way.”

Education innovation

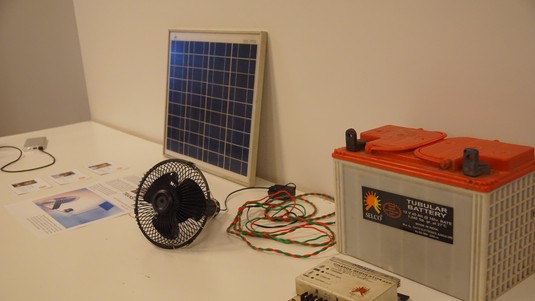

INSSINC’s organizers emphasize that the prototypes – which also included a transitional fan and a crate charger – are innovative tools, but not necessarily the program’s final product.

“At the end of the day we are developing different educational formats and innovating on that level,” says Marc Laperrouza, a researcher and lecturer in the EPFL College of Humanities (CDH).

“This is a learning experience, and the topic of this learning experience is social innovation,” adds Marius Aeberli, head of education at the EPFL + ECAL Lab.

For the past five years, Laperrouza has been leading the CDH China Hardware Innovation Camp (CHIC) – a similar educational initiative in which student projects focus on developing connected devices. While the theme changes, for both CHIC and INSSINC the ultimate goal is to explore new problem-solving and pedagogical approaches in different cultural contexts.

Currently, Laperrouza and his colleagues are documenting and analyzing the educational outcomes of the INSSINC pilot via student evaluations, in collaboration with UNIL. He says that in light of its success thus far, there are plans to continue the program, potentially in other countries.

Swiss-Indian partnership

INSSINC is a collaboration with a local partner in India, the SELCO Foundation, which works to bring sustainable energy solutions to under-served communities. The program is also made possible thanks to funding from the Canton of Vaud, as well as collaborations with swissnex India and the EPFL Vice Presidency for Innovation (VPI) Tech4Impact program.

“From the students’ points of view, I saw first-hand how empathy was key to understanding the context in which they were operating, and to understanding how best to design prototypes and solutions by eliminating assumptions. Moreover, from SELCO’s perspective, I observed that the co-creation process with EPFL students greatly contributed to helping them understand the communities in a more holistic manner,” observes Tech4Impact project collaborator Beatrice Scarioni.

Aeberli also emphasizes that at both the student and partner level, the process of developing the prototypes is one of the program’s most valuable aspects.

“The sweet spot is reaching our learning objectives and creating value for the partners. The prototypes allowed us to develop a more sustainable relationship with SELCO by exchanging knowledge, and by bringing fresh perspectives to problems through discussions with our students,” he says.

The INSSINC pilot program and China Hardware Innovation Camp are part of a wider initiative that also integrates several courses in the EPFL College of Humanities Social and Human Sciences (SHS) program. This initiative, summarized below, aims to design new learning experiences and explore different teaching formats.

Interdisciplinarity: Students from different disciplines, universities, and countries work together. In mixed teams, students from engineering, design, and social sciences experience how different perspectives, strengths, and tensions can be beneficial in grasping volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous realities.

A project-based approach, in the field, with real life applications: Students are encouraged to always keep reality in mind. Partners (investors, companies, NGOs and other organizations) provide briefs, problem statements, reality checks and feedback. Students must test their ideas, pitch, make a live demo or even negotiate. They are encouraged to consider their project from an end-to-end perspective, from problem scoping to implementation.

Human-centered design: Students are incentivized to alter their points of view to create through the eyes of someone else. Using designers’ research methods, students are asked to observe contexts, question people and exercise empathy. Their assumptions are challenged, pushing them to reframe problems and opportunities.

Possibility to fail: An environment is created to make failure acceptable and productive. This requires building trust, psychological safety, and providing students with formative feedback. Students are assessed on how they deal with different challenges and understand root causes of their success and failures. Both productive success and failure are acceptable; unproductive failure and success are not.