EPFL and Harvard unveil a joint program in translational neuroscience

© CC PloS

Harvard Medical School and Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) Launch Joint Program to Improve Quality of Life for People With Neurological Disabilities

Two universities are joining forces to combine neuroscience and engineering in order to alleviate human suffering caused by such neurological disabilities as paralysis and deafness. Scientists, engineers, and clinicians at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) will collaborate on six pioneering neuroengineering projects made possible thanks to a $3.6 million grant from the Bertarelli Foundation. Bringing together the best of U.S. medical science and Swiss bioengineering expertise, the researchers will employ the latest technologies in gene therapy, flexible electronics, optical imaging and human-machine interfaces to repair spinal injuries and hearing loss.

The collaboration launch will be celebrated at Harvard this weekend, the 28th and 29th of October, with a scientific symposium called “Neuroengineering Approaches to Sensory and Motor Disorders” that will bring together some of the world’s pioneers in the field.

Six Groundbreaking Research Projects in Translational Neuroscience

In five of the six inaugural research projects of the Bertarelli Program, basic scientists and physicians at HMS will be working with EPFL bioengineers to create new methods to diagnose and treat a wide range of hearing loss afflictions, from those that are genetically based to those caused by damage from excessive noise. A sixth project will build on novel research on spinal cord stimulation done in Switzerland, taking it a step further by implementing stretchable electronics directly on the spinal cord and attempting to rebuild severed connections through stem cell regeneration therapy.

Seeing how we hear

One of the great challenges in diagnosing hearing problems is that the physician cannot see the tissues and cells of the inner ear. In recent years, microendoscopes have been used experimentally to try to image the cells of the inner ear, but these rely on adding fluorescent dyes, something not practical for human diagnosis. At the same time, physicists have developed methods for imaging without dyes. For this project, a physicist from EPFL will collaborate with an HMS otologic surgeon to develop new imaging methods for the human inner ear. The researchers will use mouse and human inner ear tissue to optimize these new detection methods, learning, for instance, how to look through bone with long-wavelength light. Through imaging inner ear cells in animal models, they will set the stage for eventual clinical trials.

Konstantina Stankovic, Harvard/ Mass. Eye & Ear Infirmary

Demetri Psaltis, EPFL

Gene therapy targets inherited deafness

About one in a thousand children are born with some form of hearing loss, often caused by inheritance of a mutant gene. For over ten years, researchers have looked to correct a variety of inherited disorders with gene therapy, a process in which genetically engineered viruses carry corrective genes into cells affected by a mutant gene. Some early failures diminished gene therapy’s promise, but new trials in humans have been remarkably successful and have raised hopes for conditions such as hearing disorders. A problem for gene therapy is that there are few viruses known to enter the inner ear’s sensory hair cells. A pioneer in use of viruses for hair-cell physiology from HMS and Children’s Hospital Boston and an EPFL expert in gene therapy for humans will collaborate to explore new viruses to carry genes into hair cells. Through restoring sensory cell function in mice with gene mutations that mimic human deafness, the researchers will attempt to correct inherited deafness in a live mouse. This research may clear a path for developing similar tools to restore hearing function in humans.

Jeffrey R. Holt, Harvard/ Children's Hospital

Patrick Aebischer, EPFL

Treating deafness through regeneration

Much of the hearing loss that affects older people is caused by the death of sensory cells and neurons in the inner ear, a consequence of loud noise, infection, or certain drugs. This is often accompanied by tinnitus, an incessant sense of ringing in the ears. Unfortunately, these sensory cells do not regenerate they way skin or blood cells do. A first step in treating this hearing loss is to learn how to regenerate inner-ear sensory cells and neurons. Harvard scientists have recently learned how to isolate cells from a developing inner ear and to genetically reprogram them to proliferate into millions in a dish. The challenge now is to turn them into sensory cells and nerve cells. An HMS world expert in inner ear development will work closely with an exceptionally creative bioengineer from EPFL. By investigating molecular changes that occur in inner ear cells when they proliferate, and then using a micro-engineered screening platform to test thousands of compounds simultaneously, the researchers will seek to find factors that convert proliferating cells into hair cells or neurons. Finally, these factors will be tested in mice that are deaf from genetic or environmental causes.

Lisa Goodrich, Harvard Medical School

Matthias Lutolf, EPFL

Delivering drugs to treat hearing loss?

Once scientists learn to regenerate sensory cells in the laboratory, it is still a huge leap to make this happen in a human patient. The right drugs or chemical factors must be delivered to the inner ear, held in the right place, and released slowly over months, all without damaging the delicate sound-sensing structures. In this project, a pioneer in hair-cell regeneration from HMS will work with an EPFL bioengineer specializing protein engineering and nanotechnology techniques to develop new ways of delivering regenerative factors to the inner ear. Bound to hydrogels or packaged in novel "polymersomes” the factors will be taken up by the remaining cells, and will reprogram them to proliferate and morph into sensory cells.

Zheng-Yi Chen, Harvard’s Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary

Jeffrey Hubbell, Head of EPFL’s Institute of Bioengineering

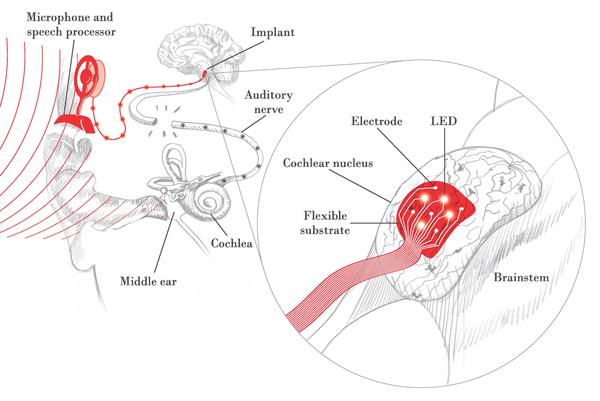

New generation of auditory brainstem implants

The cochlear implant (CI), a device that bypasses the deaf inner ear to convey electrical signals directly to the auditory nerve, has been the most successful neural prosthesis over the past few decades, with over 200,000 in use worldwide. However, some patients cannot receive the CI due to an absent or damaged inner ear or auditory nerve. The auditory brainstem implant (ABI) in its current form bypasses the auditory nerve to directly stimulate the central auditory pathways found in the brain using a rigid electrode paddle. Unlike most CI users, the vast majority of ABI patients do not understand speech and many have side effects due to electrical current spread. An exciting new approach is the use of light, or optical stimulation, to provide more selective activation of auditory neurons.

An interdisciplinary team of EPFL engineers and HMS scientists and surgeons will develop and test a new flexible array of electrical and optical electrodes that will conform to the surface of the brainstem and stimulate the central auditory pathways in a more precise manner. This work will enhance the performance of existing ABI devices, and provide the basis for a new generation ABI device.

Daniel J. Lee and Christian Brown, Harvard/ Mass. Eye & Ear Infirmary

Stéphanie P. Lacour, Philippe Renaud and Nicolas Grandjean, EPFL

Walking again

A complete spinal cord injury leaves a person paralyzed with no hope of recovery, because the brain can no longer send signals to body’s extremities. EPFL has already made groundbreaking research in spinal cord stimulation using electrodes and pharmaceutics to reawaken the dormant circuitry that controls the legs, allowing animals to walk again, but involuntarily. For this locomotion to become voluntary, signals must come from the brain. HMS is working on silencing two genes that could lead to the re-growth of the neural fibers severed in the accident, bridging the injury and re-establishing voluntary leg movement when coupled with stimulation.

Zhigang He and Clifford Woolf, HMS/ Children's Hospital

Stéphanie P. Lacour and Grégoire Courtine, EPFL