DNA brings materials to life

© 2013 EPFL

DNA-coated colloids have been used to create novel self-assembling materials in a breakthrough experiment by EPFL and University of Cambridge scientists.

A colloid is a substance spread out evenly inside another substance. Everyday examples include milk, styrofoam, hair sprays, paints, shaving foams, gels and even dust, mud and fog. One of the most interesting properties of colloids is their ability to self-assemble – to aggregate spontaneously into well-defined structures, driven by nothing but local interactions between the colloid’s particles. Self-assembly has been of major interest in industry, since controlling it would open up a whole host of new technologies, such as smart drug-delivery patches or novel paints that change with light. In a recent Nature Communications publication, scientists from EPFL and the University of Cambridge have discovered a technique to control and direct the self-assembly of two different colloids.

Contrary to solutions that are made up of discrete molecules, colloidal solutions are made up of large particles, dispersed in a liquid solvent. This unusual structure gives colloids unique properties such as Brownian motion (the random zig-zag movement of particles as they collide with the molecules of the dispersion medium), electrophoresis (the unidirectional movement of particles under and electric current) and optical properties such as the Tyndall effect (light entering a colloid scatters and exits as a different color). It is because of such properties that colloids are so commonplace in everyday life; but one particular property holds special interest: self-assembly.

Self-assembly refers to the ability of a colloid’s particles to spontaneously form a kind of stable structural arrangement as a result of the shape and direction of the colloid’s particles as they interact with the dispersal medium. Although no external force is required, self-assembly generally takes place as a response to a change in an environmental factor such as temperature, light, etc. In biological colloids like DNA, proteins and other macromolecules, self-assembly is usually the first step to self-organization, which underlies many cellular structures. But in terms of technology, self-assembling colloids could have a wide range of applications, fuelling much research in the field.

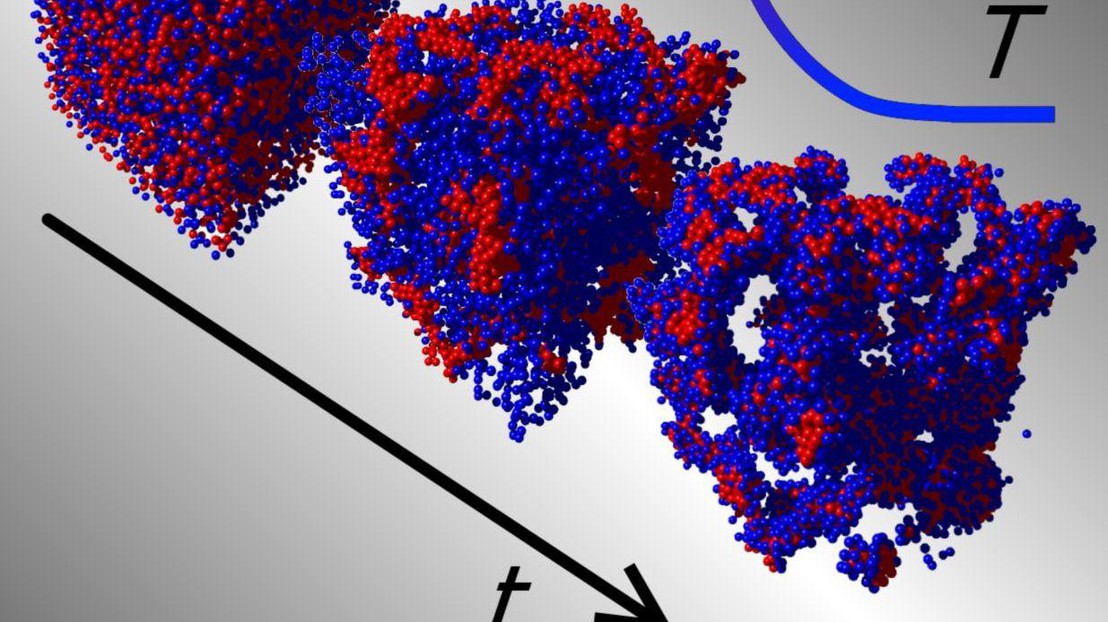

But what about self-assembly of two – or more – species of different colloids? This is the question addressed by Giuseppe Foffi’s group at EPFL, working in collaboration with Erika Eiser’s group at the University of Cambridge. The scientists showed that when the interactions between the particles of two different colloids are carefully designed, they result in the formation of new structures. Specifically, they have discovered a way to obtain self-assembled structures that depend strongly on temperature changes. Giuseppe Foffi (who is now at the Laboratoire de Physique des Solides, University of Paris-Sud) says: “In a sense, the new structures have a ‘memory’ of their preparation history.”

Using DNA-coated colloids, the group of Erika Eiser was able to control the self-assembling progress between two different colloidal species. Fluorescent polystyrene spheres were coated with different DNA strands (giving them a ‘hairy’ appearance) that acted as means of particle interaction and can be used to characterize the different species. The advantage of using DNA strands was that the interactions between the particles could be programed using the compatibility of the DNA sequences. Another very interesting property is their responsiveness to sharp changes in temperature, offering a high degree in specificity and programmability. The two species of colloids were mixed together in a ‘binary mixture’ where one could aggregate faster, therefore creating a structural ‘scaffold’ for the other to assemble upon.

By exploiting the selectivity of DNA base-pairing, supported by simulation studies by the EPFL group, the scientists found that they could achieve an unprecedented control of the morphology of the interacting colloids. By gathering data about the system’s morphology and the dynamics of particle interactions, the authors concluded that this approach is not restricted to nano-scale objects like other methods, but can be applied to the entire range of colloidal sizes. In addition, they foresee that this method can have a number of applications, for example light-reacting paints or smart patches that respond to changes in the body’s temperature or pH by releasing particles filled with a drug like an antibiotic or antipyretic.