Discovering the essence of Le Corbusier in his apartment-studio

The living-room, in 2014. © G.Marino / EPFL

How should an iconic piece of modern architecture be restored? Two EPFL researchers took up this challenge, tracing the history of Le Corbusier’s apartment-studio in Paris. They published their findings in a book, which includes restoration guidelines that draw on previously unpublished sources of information about the Swiss architect. The book launch will take place on 7 May at EPFL.

“It was a risk to try living in my own architecture. But it turned out to be magnificent.” Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, penned these words in a letter to his mother on 29 April 1934. The celebrated architect had just moved into the top floor of a building that he had designed at 24 Rue Nungesser et Coli in Paris, near the Bois de Boulogne park. This quote also opens one of the chapters of an EPFL book written about that apartment, which, from 1934 to 1965, served as Le Corbusier's painting studio and architecture lab.

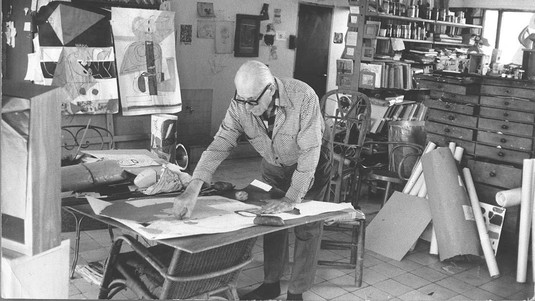

The book’s authors, Giulia Marino and Franz Graf, are researchers at EPFL’s Laboratory of Techniques and Preservation of Modern Architecture (TSAM). They were commissioned by the Fondation Le Corbusier, with funding from a Keeping it Modern Grant from the Getty Foundation, to come up with a list of guidelines for fully restoring this unique site so that it can be opened to the public. As part of their work, they had access to previously untapped sources of information, which they publish and cite in their book: these sources include photos, letters and first-hand accounts provided by people who were close to the architect.

Le Corbusier tested out his architectural ideas in his apartment. As a result, it played host to a combination of styles dating from 1930 to the 1960s and ranging from a ‘purist’ interior to a ‘brutalist’ feel – Le Corbusier was constantly changing the apartment’s interior and trying out different materials as he experimented with architecture. So what should be considered the core period? What should be preserved? What can be done away with? What story should be told? The researchers came up against these and many other questions, always aware that they were dealing with a true legend – a legend they dented at times. We spoke with Giulia Marino in the run-up to the book launch on 7 May and the reopening of the apartment-studio to the public in June 2018.

What sort of options does a restorer have in turning a famous architect’s apartment into a museum?

There are many examples of what can be done. You can, for example, recreate the interior, giving the impression that the architect has just stepped out. That’s how Ernö Goldfinger’s London apartment, which we visited, is set up. There, the concept is taken to the extreme, with cans of baked beans and a bottle of ketchup in the kitchen! But there’s a risk of giving the place the feel of a wax museum. At the other end of the spectrum, Milan architect Vico Magistretti’s former office has been turned into an exhibition space with offices for the foundation’s staff, although some original features have been kept. In other cases, the interior is left completely empty, like in Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye just west of Paris.

What is it that stands out about Le Corbusier’s apartment-studio?

It’s a manifesto, a unique concentration of his inventions, such as the brise-soleil – which protects a building from sunlight – and indirect lighting. There is also Modulor Man, a human silhouette whose proportions served, among other things, to define the dimensions of his famous housing units. It is present in the form of stained glass in the dining room's bay window. In addition, we realized that the reason Le Corbusier covered some walls and ceilings with oak plywood was to hide water stains from leaks in the roof. This is rather ironic, since this type of paneling then became a fixture of modern architecture! From an ethical perspective, we found it impossible to favor one period over another. So we proposed to preserve the way Le Corbusier left his apartment – a palimpsest of eras.

How did the unpublished sources that you consulted help you develop your recommendations?

A lot of photos were taken of the apartment, but many of them aren’t dated. So we had to come up with ways of putting them into chronological order, such as by carefully looking at the works of art in the images. By comparing hundreds of photos, we saw how the space changed over the decades, how furniture, materials and artwork came and went, and how certain aspects remained constant over the years, such as a red painted wall in the living room and the location of particular objects and paintings. Le Corbusier was a painter and a collector too. For us, placing carefully selected objects (paintings, rugs, sculptures) in strategic locations where they have always been is crucial if visitors are to truly understand the architecture and how the space was used. We also studied his correspondence, his bills and the impact of the countless – if not always felicitous – renovations that the apartment went through after his death. We also came up with recommendations on additional studies that are needed before any restoration work can begin, such as analyzing the layers of paint to identify all the colors used, since such things cannot be identified with any accuracy from the black and white photos. Now it’s up to the architect-restorers and exhibition specialists to review our guidelines and factor in the necessary security measures so that they can come up with a display approach that will be of interest to both researchers and the broader public.

Does the apartment-studio reflect Le Corbusier’s day-to-day existence?

The apartment was indeed in keeping with how the architect and his wife lived. It was divided into two parts, separated by two pivot doors. Le Corbusier’s painting studio was on one side and the other side was where the couple, who didn’t have any children, lived – sitting room, bedrooms, kitchen and dining room. There is also a lovely terrace on top of the building. There are numerous stories about Le Corbusier’s wife Yvonne who, according to people who worked with Le Corbusier, was not allowed to enter his studio. Le Corbusier himself noted that, after his wife complained about 'living in a barrack' – an expression we find in his correspondence – he developed the principle of indirect lighting, in which artificial light is projected onto a colored wall. This invention became iconic both in his work and beyond it.

Presentation of the 2nd edition of the Cahiers du TSAM; Introduction with Christine Mengin, General Secretary of the Foundation Le Corbusier

Moday 7 May 2018 - 6:30pm, Project Room, SG Building, EPFL.

Giulia Marino, Franz Graf, 1931-2014: Les multiples vies de l’appartement-atelier Le Corbusier, Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, 2017.