Contribute to Science by Locating Geneva's Wildlife Habitats

© erikpaterson / Flickr under a creative commons license

How are toads faring in our cities? Not too bad, at least in the Geneva area. Scientists are calling on residents to share their local knowledge on a new web platform in an attempt to learn more about the genetic diversity of plants and animals in our concrete jungles.

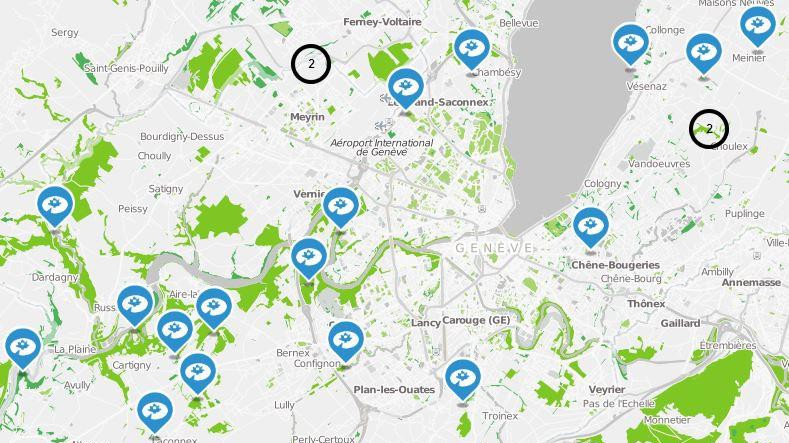

Cities are teeming with wildlife, much of which goes unnoticed, hidden away in urban parks, gardens, and other secluded niches. But the impact of urban development on the long-term survival of plant and animal populations is still poorly understood. Now, researchers are calling on the people of the greater Geneva area, on both sides of the border, to help locate habitats of the common toad. Participants are asked to report the location of ponds on the unique and fun interactive UrbanGene website. They can also follow the project’s evolution on social media via its Facebook group.

Genetic diversity is crucial for plants and animals. In the long term, it allows them to adapt to threatening situations, such as a changing climate, new predators, or diseases. But boxed into ever-smaller communities by roads, buildings, and other urban infrastructure, this life-saving diversity could be in peril. “We are trying to find out what happens genetically to plant or animal communities when obstacles split them into ever smaller groups,” says Stéphane Joost, principle investigator of the UrbanGene Project.

Cheek-smears from toads

Residents of the Geneva area are called upon to help scientists fill the gaps in the database of urban ponds, common habitats of the toads, by entering them into a website. With permission from the landowners, a group of researchers would then visit each site in search of toads, from which they would extract a DNA sample by collecting some cells from the inside of the their mouths. After decoding their genetic information, the results would be plugged into a geographical information system for further analysis.

Plants, toads, and butterflies

In the course of the project, the researchers will focus on three plant and animal species that are prevalent throughout the greater Geneva area: the common toad, the meadow brown or small white butterfly, and the broad-leafed plantain, a common weed. “By scanning the genomes of these organisms for a large number of genetic markers, we will be able to assess their genetic diversity and determine how it varies in response to urban densification,” says Ivo Widmer, a biologist and an expert in environmental genetics working on the project. The studies are timely, with many urban development and densification projects on-going across the territory that is split between Switzerland and France. And results could provide valuable insight to guide future sustainable urban development projects across the greater Geneva area.

The flow of genes in space and time

The UrbanGene project is breaking new ground by tracking three species that differ starkly in how they spread their genes. Plant DNA spreads by the wind, bees, and other pollinating insects. And while toad DNA travels by land, as the animals move from pond to pond, butterfly DNA takes to the sky. Because of these differences, the sensitivity of each species’ biodiversity to urban development is likely to differ strongly. The project will initially focus on understanding how the genes of animals and plants from different habitats are connected to each other. Follow-up studies will study the diffusion of genetic information across habitats over time.

According to Sandra Mollier, Head of Agriculture, Nature, and Landscape at Le Grand Genève, one of the organizations funding the project, these abstract-sounding findings will have very practical implications. “Promoting a multipolar and urban agglomeration that allows urban wildlife to thrive is particularly important to us,” she says. “If, for example, through this project, we realize that certain plant or animal communities have become increasingly isolated because of urban construction projects, its findings could help us take effective steps already in the planning phase of future projects to reconnect them again.”

A three-pronged approach

The project is being carried out in parallel to GreenTrace, an effort by EPFL, UNIL, UNIGE, and HUG researchers to understand the benefits provided by urban biodiversity. But pinning down its effect on a city’s residents is tricky business, because reported perception and measured reality often do not align. “To get a more accurate picture of the relationship between urban development and urban wildlife, we will be working on three levels. Genetic analysis will inform us of the impact of development projects on the plant and animal species. An extensive survey will reveal how people perceive urban wildlife. And using health data, we will be able to assess whether and how proximity with urban green spaces and wildlife has a concrete, measureable impact on actual physical well-being.”