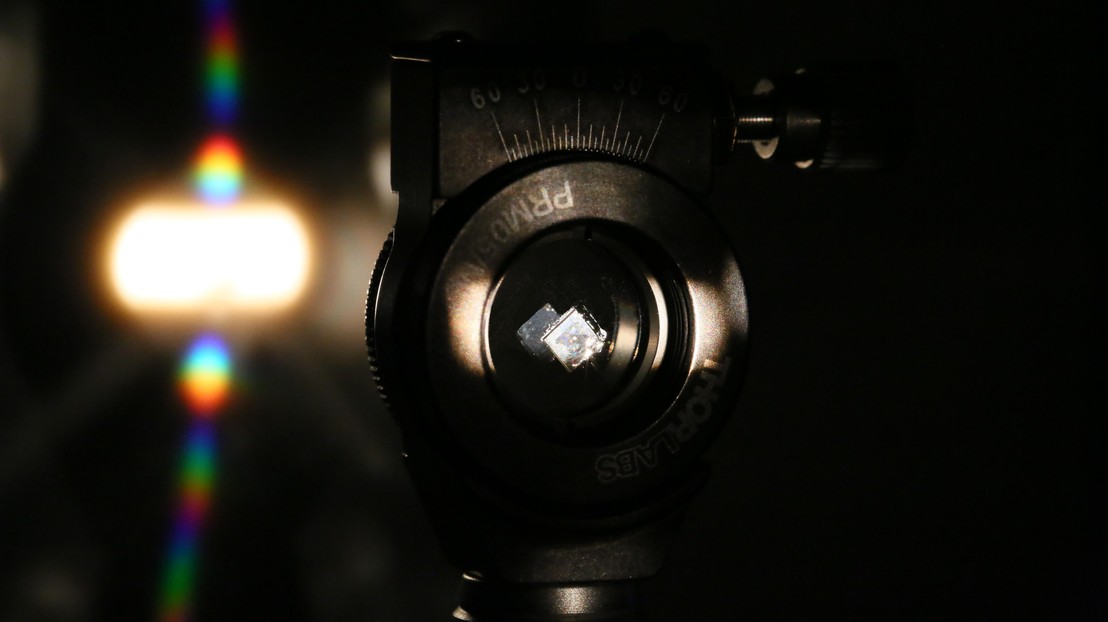

Carving diamonds for optical components

© Alain Herzog / EPFL 2017

Thanks to a new technique developed at EPFL, optical diffraction gratings can now be made out of pure diamond, with their surfaces smoothed down to the very last atom. These new devices can be used to alter the wavelength of high-powered lasers or in cutting-edge spectrographs.

A team of EPFL researchers has developed an unconventional way of microscopically cutting diamonds into a particular shape and smoothing them at an atomic level. This new technique, which will be presented at the International Conference on Diamond and Carbon Materials DCM2017 on 5 September, makes it possible to manufacture diffraction gratings out of pure diamond, which has unique properties that are ideal for both spectroscopy and the optical components used in high-powered lasers.

Diffraction gratings are made up of parallel grooves that break up light into its spectral components, kind of like a prism. These gratings are usually made out of glass and silicon, materials that have already been used in spectrographs and to alter the color emitted by lasers.

The team, led by Niels Quack, a SNSF-funded professor at the School of Engineering, has now found a way to make these gratings out of single crystal diamond as well, opening up the field to an array of new possibilities. Diamonds are unmatched in terms of their thermal conductivity, which is between five and ten times greater than that of any other material used for this purpose. Diamonds are also extremely hard and work well with UV rays, as well as infrared and visible beams. "Diamonds are chemically inert, which means that even the most aggressive chemical substances can't attack them. But it also means that they are very difficult to machine," explains Dr. Quack. "So this new way of carving diamonds could prove very useful."

Using oxygen to cut diamonds

The technique developed by the researchers is groundbreaking because it allows them to etch well defined shapes into millimeter sized single-crystal diamond plates, with the grooves separated by just a few microns and with incredibly smooth surfaces. To develop their technique, the researchers used diamonds created synthetically through chemical vapor deposition.

The diamonds are etched in several stages. First, a hard mask is deposited and structured on the surface of a diamond plate, which is then exposed to an oxygen plasma. The oxygen ions in the plasma are accelerated onto the surface of the diamond by an electric field. Where not covered by the hard mask, the oxygen ions remove carbon atoms from the diamond’s surface one by one. "By adjusting the intensity of the electric field, we can alter the shape we etch into the diamond," explains Dr. Quack. "For the diffraction gratings, we carve out triangular grooves that are just a few microns apart from each other. We adjust the process parameters to selectively reveal a set of well-defined crystal planes, allowing us to create V-shaped grooves that are smoothed down almost to the atomic level. It is impossible to get this kind of precision when the diamonds are simply cut with a laser."

This new technology, which was developed using the facilities in the Center of MicroNanoTechnology (CMI), is the subject of a recent patent application. The same principle has already been used using silicon, but it had never before been demonstrated in diamond. In recognition of the importance of this contribution, doctoral student Marcell Kiss has been shortlisted as one of the six finalists of the Young Scholar Award DCM2017.

EPFL Quack Group Q-LAB

The researchers are collaborating on this development with LakeDiamond SA, a Swiss manufacturing company of high purity single crystal diamond substrates.

The project is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) and by the Gebert Rüf Stiftung.