Artificial aorta can reduce patients' blood pressure

© Félix Wey, Werner Siemens Stiftung / 2021 EPFL

Engineers at EPFL’s Center for Artificial Muscles have developed a silicone aorta that can reduce how hard patients’ hearts have to pump. Their breakthrough could offer a promising alternative to heart transplants.

“Over 23 million people around the world suffer from heart failure. The disease is usually treated with a transplant, but because donated hearts are hard to come by, there is an ongoing need for alternative therapies. With new developments in cardiac assistance systems, we can delay the need for a transplant – or even eliminate it altogether,” says Professor Yves Perriard, head of EPFL’s Center for Artificial Muscles within the School of Engineering. He and a team of around ten other engineers from EPFL’s Integrated Actuators Laboratory (LAI) have been working on new cardiac assistance technology over the past four years. Their discovery, which employs flexible actuators, has been published in Advanced Science.

Electrodes and a silicon aorta

Our aortas are naturally elastic. They expand as blood is pumped into them from the heart’s left ventricle, and then contract to distribute the blood to the rest of the body. But in patients suffering from diseases such as heart failure, the heart has to work harder to accomplish this cycle. To ease the burden on the heart, EPFL engineers have designed an artificial aorta made of silicon and a series of electrodes. Their device is implanted just behind the aortic valve and amplifies the aorta’s efforts, working like an “augmented aorta.” When an electric voltage is applied to the device, the artificial aorta expands to a diameter that’s larger than the natural aorta. “The advantage of our system is that it reduces the pressure on a patient’s heart. The idea isn’t to replace the heart, but to assist it,” says Yoan Civet, a Scientist at the LAI.

Helping the heart expend less energy

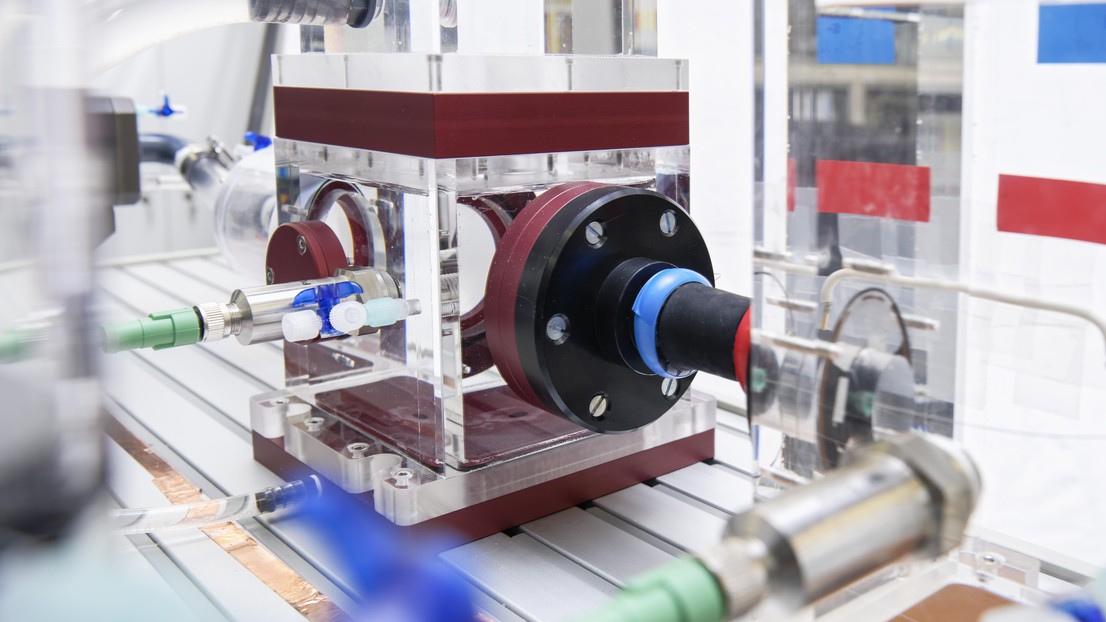

To validate their system, the engineers built a simulator consisting of pumps and chambers that replicate the blood-flow and pressure conditions within a human heart. “By testing our device on the simulator, we were able to reduce the amount of cardiac energy required by 5.5%,” says Civet. The research team now plans to conduct further tests of their artificial aorta, and are already working on a new design that delivers better performance.

However, the real challenge lies in the manufacturing step. “We started from scratch and had to develop a new production process that would allow us to increase the volume of the silicone tube. We also had to overcome a problem of electric breakdown. Due to our multi-layer design, only half as affordable electric field was reached as compared to a single-membrane system. We had to troubleshoot the problem and then come up with a solution,” says Civet. The research team has filed a patent for their technology. The hope is that their discovery can be used to treat other medical conditions, such as urological disorders, that require a similar approach.

This research was carried out under a joint initiative by ETH Zurich, the University of Bern and EPFL. The consortium has received a 12-year, CHF 12 million grant from the Werner Siemens Foundation to develop a cardiac assistance system, a urology system and a facial reconstruction system all based on flexible actuators.