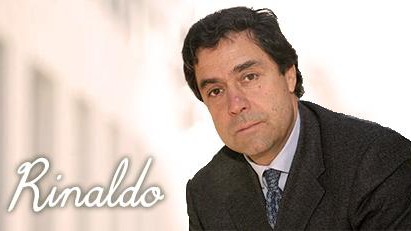

Andrea Rinaldo honorary doctorate from INRS, Québec

© 2014 EPFL

"INRS (Québec) is paying tribute to professor Andrea Rinaldo’s outstanding career in water sciences and and innovative interdisciplinary contribution to ecohydrology by awarding him a honorary degree."

www.inrs.ca/actualites/l-inrs-decerne-un-doctorat-honoris-causa-au-professeur-andrea-rinaldo

www.univiu.org/conferences/upcoming-conferences/honorary-doctorate-to-prof-andrea-rinaldo

ANDREA RINALDO

ACCEPTANCE SPEECH

Cérémonie de remise d’un Doctorat honoris causa

de l’Université du Québec sous l’égide de l’INRS

Venice International University, San Servolo, Venice

M. le Recteur de l’INRS Daniel Coderre, Mme. la Présidente de l’Université du Québec Sylvie Beauchamp, Mme. la déléguée du Québec a Rome Amalia Daniela Renosto, Eccellenza Ambasciatore Umberto Vattani, distinguished Faculty members of the Université du Québec and INRS, dear colleagues and friends, chers collègues et amis:

Let me warmly thank all those who were instrumental to my receiving this honor today – so unexpected, so dear to me – with gratitude and a sense of novel and proud belonging to your Institution. I am especially moved by the motivation you have chosen, one that prides me and leads to my commitment to establish lasting ties with your Institutions in the future.

The occasion is quite special for me, of course. This is so, in the greatest part, for the great honour bestowed on me through your highest academic recognition, which I accept humbled and proud at the same time. It is also a special occasion for the location you have chosen for this ceremony, in the beautiful island of San Servolo hosted by the prestigious Venice International University whose ranks you have recently joined. As you may know, I was born and raised in Venice, and this – despite my many loyalties and loves drawn from a lifetime spent elsewhere – will always remain my city, il mio luogo dell’anima, the place of the soul. Venetians are peculiar: they tend to think of their place as the city at the center of the world, as Shakespeare put it. In a modern reading of the same concept, Venetians view the fragility and the resilience of their built and natural environments, facing the vagaries of Nature, as the central episode of the crisis of modernity. So do I, of course. The origins of their deeply-held belief of centrality may perhaps be traced back to the forcibly self-relying nature of Ur-venetians, owing in large measure to the local lack of prime materials which was instrumental in determining conditions opposed to the natural isolation of the city. The lack of basic materials thus favored the personal initiative and autarchic choices, in yet another twist of the meta-history inescapably dominated by climatic and environmental factors.

Finally, this is also a treasured occasion to reflect on important, rather then urgent, issues about our mission in research and education. This is therefore the subject of my speech, fearing boredom especially after I discovered that there exist scholarly papers on the statistics of the structure of acceptance speeches – all alike, it seems. I speak to you, in fact, humbled but determined to make a point on relevant scientific and academic issues, also fit to the occasion of the Workshop you have kindly organized aiming at the future of hydrology. I harbor well-formed opinions on both scientific and academic matters. I believe that, speaking as unauthorized voice of an entire academic generation, we have a few urgent things to do in the near future. Indeed learned Institutions (among which I count Universities, research Institutes and Academies) can and should do something to counteract the short-sighted, short-term attitude that permeates today’s society. We can because we are not in charge of today’s economy and science, but rather of the economy and the science 20 years from now. This is so because the people we educate will create the economics and scientific research of the future. We must preserve this unique prerogative at all costs. This is the Academician’s timeless task naturally projected into the future: to encourage a broad education of young people; to offer them challenges that will measure them; to see ahead of time where science and education are to be led. It is an especially gratifying challenge.

2. About research. Future of hydrology. It is customary on such occasions to speak about one’s discipline, to pause and look across its cultural landscape to probe the current state of affairs and divine its future. I shall make no exception, with an added twist -- as Venetian-born and a hydrologist, graduated in Hydraulic Engineering at the University of Padua (as my late beloved father, Aldo, and my brother Daniele but also my late father-in-law, Alberico Putti whom I always remember, and his son Mario, colleague and dear friend who is here today): I view the planetary metaphor of Venice at an angle, one that looks at water through the centuries as instrumental to the making, the thriving and the very survival of the city. Water laws and water-governing decrees have been countless in the 1,000 year long (or so) span of deliberations of the Serenissima Repubblica. Well beyond mere technical aspects, they came to embed sanitary, environmental, business and strategic matters basic to survival, prosperity and military defense – pertaining the very existence of Venice, the city and thus the Nation. The lesson of the survival of Venice in such a fragile and ever changing environment legitimately becomes the magnifying glass through which the entire realm of modernity ought to be seen, together with the implications of a unique, complex and ultimately spectacular co-evolution of built and natural environments. So, for that matter, it is natural for a venetian to conceive water as essential for life and as a tough partner in trade, inescapably (by Egnazio’s Huius edicti ius ratum perpetuumque esto) eternal frontier.

Sustainability itself, a fashionable and often abused concept, is challenged by the Venetian history and its metaphors. Sustainability, in fact, implies our capability to provide our offsprings with resources and opportunities comparable to the ones that were given to us. It also implies a reference state of the environment which in principle one should preserve – this concept permeates the environmental literature, the whole conservationist thinking in fact. And yet one wonders ‘what if’ no preferential state of the environment exists. What if in the evolutionary dynamics of the landscape there would exist thousands of very different, yet equally likely configurations of the ecosystem embedding man’s artifacts? In the evolutionary dynamics of a transition landscape to be built and destroyed by tidal currents of brackish waters there would exist thousands of very different, yet equally plausible states in which open, dissipative systems endowed with many degrees of freedom could settle in. Lagoons are punctuated by scattered or systematic outcomes of the built environment that quench their evolution providing diverging evolutionary trajectories. The hydrologist knows that the very idea of conservation becomes meaningless if not misleading in such cases. Mankind, in such fragile and unstable environments, should design the desired ecosystem services (physical, biological, cultural, strategic to name a few) and engineer them, unregretfully and wholeheartedly (as was demanded to the Serenissima Repubblica, say, through the diversion of five major freshwater tributaries of the lagoon through almost the entire course of history). Pursuing such services will have to be made in total disregard for the general directions of the spontaneous evolution the system would experience otherwise. Venice showed the world the worst type of Earth engineering, as it came to be called in recent times, a darkly resounding name. It has been so, around here, for more than a thousand years to suit the mutable models of social and economic development of Venice. Without this, you would have arrived in San Servolo today by driving your car and parking it right here – in one among yet many possible divergences that rewinding the tape of time would have produced. This is why I hold deep beliefs – as a water scientist and as a venetian – that hydrology matters for the fate of humanity and welfare equally at global and local scales. This is also why I believe that claiming that today’s lagoon is untouchable is, on conceptual and historical grounds, a meaningless prejudice. It is the way we probe how to touch it that makes all the difference.

Floods, droughts and a fair distribution of water: these are the traditional building blocks of the discipline. Around those, the discipline has evolved, and learned Institutions truly d’avant-garde should ride the wave of change and foresee where the boundaries of research and knowledge are moving. This is the heart of scientific research and of academic excellence anywhere and anytime. In this process, we sense «that a transformation to deeper understanding is pressing upward in some as yet poorly articulate form». I believe, jointly with my dear colleague and friend Ignacio Rodriguez-Iturbe, that we may very well be in such a period in hydrology. Signs abound. Think, for instance, of the radical change in the way we now perceive and measure the geometry of Nature and decoded its mysterious mathematical language: we came to realize with Benoit Mandelbrot that «clouds are not spheres, mountains are no cones (…) coastlines are not circles nor does lightning travel in a straight line». Hydrologic research has gained centerstage in a broad, interdisciplinary research milieu that explains many patterns in nature and their signatures (and perhaps the dynamic origins) of self-organization. River networks (their statics, dynamics and complexity) played a central role in that transfer towards other disciplines, attitudes and tools, largely due to our outstanding ability to observe Nature over a broad range of scales. This firmly placed hydrologic research at the frontier of contemporary science. Let me reinforce my main point on the lessons drawn from such a precious exposure: What matters is the challenge posed by the questions we ask rather than the answers we contrive – imperfect and limited as they always are. The sheer pleasure of scientific research and of sharing it with peers and students hinges on its intrinsic interdisciplinary nature. The excitement of being a hydrologist today is fueled by the endless frontiers of our work that we discover.

River networks are a good example, I believe, and a lifetime interest of mine: form and function, beauty and challenge, evolution and self-organization. What is the source of the infinite diversity and yet the deep symmetry of the forms we see in the fluvial landscape? Why can one remove the scale bar from the map of a river network and mistake a creek for the Amazons? River networks served us well in understanding the signatures of critical self-organization in Nature. Currently, moving from our deep understanding of the symmetry of the parts and the whole built in their structure, they lead us into something new and unexpected. River networks seen as ecological corridors for species, populations and pathogens of waterborne disease open up to a world of new scientific challenges. Will large scale water resources management plans include the preservation of biodiversity so dramatically imperiled worldwide? Do we understand hydrologic drivers and controls of the spreading of waterborne disease? Is the morphology of a fluvial ecosystem a template of the services it provides? How did landscape heterogeneities and river network structure affect human population migrations, and thus meta-history as a whole? Migrating populations needed to follow river routes to access water resource and so do biological invasions of freshwaters. And more: What does ‘fair distribution of water’ really mean in a world where the inequalities in the wealth distribution are so marked, despite the early XX century’s optimism embodied by the Kutznets curve? Is it Marx or is it Piketty, then, and one wonders about the role of the environment.

The kind motivation you have chosen mentions the welfare of humanity, something I deeply care for, and the theory on which my group has been passionately working for several years that, in your kind words, permites de prédire avec precision la propagation de maladies transmises par l’eau. I am grateful for this mention which is dear to me for it highlights what I have been striving to achieve, for science and welfare. Indeed models are fun, and sometimes even instructive: and in this case we may add even useful, like predicting in time for intervention the deployment of life-saving supplies or medical staff or the effects of alternative management strategies of cholera epidemics. Addressing such issues seems like a moral imperative for the north of the world. The social and ethical aspects of our work should never fail us – as the business of a truly fair distribution of water unerringly implies. It is a most important aspect for me. And, again for I would hate to miss this chance for providing an outlet to my long as hitherto unexpressed meditations in the train rides between Padova and Lausanne, other issues are pressing. Do we fully understand the role of hydrology on the virtual water trade and thus on food security? We must metabolize the lesson of Partha Dasgupta and of vastly contrasting readings of societal drifts built on economic models where «nature does not get a look in except as a bit player, nor is there a possibility that population pressure could contribute via habitat destruction to the persistence of poverty and hunger». Nature is life’s support but orthodox economic theory is oblivious of its role as a capital asset. Is nature simply «a luxury that can wait to be taken care of until the economy generates sufficient incomes»? Perhaps ‘environmental’ Kuznets curves should be rejected as a metaphor for development prospects. With those eyes we should look at the global virtual water trade, for example, and to hydrology as a whole as key to our rethinking food security. Dubbing a rather different citation, I like to conclude that he who knows only about hydrology, knows nothing of hydrology.

These are the questions that we wish to address. Way too many for my generation to address in full or even to scratch them beyond the surface, we shall leave them to the young colleagues who are at no risk of being left idle -- but, alas!, perhaps in need to be protected (especially from the political hydrologists in fashion) to secure reward for the truly important and thus a proper place in the earth sciences of tomorrow. From spatially explicit epidemiology of waterborne disease, to biodiversity in the fluvial ecosystem, to the fate of transition environments like lagoons, deltas, estuaries and wetlands, to the ultimate stability of the globalized world of virtual water trade: it’s all in the water.

All this should be reflected in adapting our teaching. While hydrology has yet to be fully characterized, as a discipline it is broken down into increasingly refined detailed specialties out of an anti-consilient, reductionist knowledge system. Sub-specialties are increasingly refined and keen on speciating. Yet the basic training we provide is still confined within a straightjacket created many moons ago as a part of civil engineering course of studies. This is clearly no longer in keeping with today’s situation, and we need to update, remodel and rethink our educational package with a broad view to our users from both the engineering and the earth sciences communities. A fair solution will naturally lie in adopting wider frameworks as suited to the audience proper to one’s school.

I would finally like to add my own response to the crowded, longstanding debate on whether hydrologic research should be part of engineering, problem-solving oriented, of or the geosciences, observation driven as they always are, or maybe of the environmental sciences tout-court: who cares? Theory, experiments, field work and problem-solving should all be part of our trade. A modern hydrologist needs to be capable to design an experiment, to understand the meaning and the implications of stochastic differential equations, to put on boots and jump in a stream to carry out hydraulic measures or interact with emergency Civil Protection or Public Health officers, because we are specialists of the problem, not of the tool. Technical proficiency is needed to be possibly able to innovate, but the impact of our work will be always be measured on the importance of the scientific questions we ask and on the social and economic relevance of the problems we address.

3. About education. Antidotes to unwanted societal drifts and the building of our future. An educated person – our output -- must be able to think and write clearly and effectively, communicating with precision, cogency and force as Henry Rosowsky famously put it. Moreover, he/she should have developed a critical appreciation of the ways in which we gain knowledge, strictu sensu about the subtleties of his/her specialty but more in general, one assumes, about ourselves and society at large. For us, this translates into the need to become technically impeccable and reasonably aware of past achievements prior to any chance of proving truly innovative. An informed acquaintance with the mathematical and experimental methods of the physical and biological sciences is essential, as well as the no-nonsense approach of the engineer, never to be underestimated. We should train open minded young souls, never provincial in the sense of being ignorant of other cultures, languages, modes of thinking and lifestyles. The wider world is a necessary reference for our lives today, and a broader dimension is necessary. Actually, on a personal, political vein spellbound by the abysmal level of the political discourse in Italy today: Europe is our only hope.

This we must transfer to the new generations, together with allegiancy and sense of belonging to a wider context (the global village, one may contend, or the commons – simply downscaled to Europe for Italy now). And yet we should always be able to convey, together with the ability to meet scientific challenges, that of thinking about moral and ethical problems raised by one’s work. This in not difficult to conceive if your work aims at a fair distribution of water anywhere in the world or at reducing inequalities even if from the sole perspective of granting access to safe drinking water or adequate sanitation. The ease of spread of waterborne disease through waterways and human mobility networks remains a global societal challenge in the XXI century, a shame in a technologically literate world. This must be our legacy, making sure that our students have achieved depth in our field of knowledge with a heart. Long is the distance from the brain to the heart, in Musil’s words, when the hard obstacle of the slide ruler sits on your breast pocket. No more, I hope.

I have also been fortunate – passionate as I still am about academic policy, a habit since the rewarding years I spent in the then newborn University of Trento -- to be in a condition to compare different academic systems, in Italy, Switzerland and the US. Details should not be central to a broad view of education, and I would like to sketch a few lessons I learned while being in the Faculty of rather different Institutions as far as tradition, size, ambitions and vocation are concerned.

First, perhaps unexpectedly, I came to value the peculiar features of the Italian education, especially in secondary school. Therein the challenge to the students, unheard of by fellows outside the European schooling system, regardless of the subject taught sharpens the habit of attention, the art of expression and that of adapting quickly to a new intellectual posture, stimulating debate and critical thinking. I still think that my study of ancient Greek in high school gave me the gift of learning how to study – though I lost entirely the subject I studied then. A challenging, unforgiving schooling system is a school of self-knowledge. So is a crowded undergraduate education like the one I had in Padua where much, much is left to one’s initiative, exams are unfairly encompassing way more material than that taught in class and attention to individual needs is null. This state of affairs leads to the peculiar idiosynchratic Italian output with the broadest possible resulting distribution for the knowledge of the students – in whose upper tail lie treasures. I would not trade it, its obvious defects notwithstanding, for the maternal protection offered by other systems where priviledge and CV building, in most cases carefully designed by the families, make all the difference.

The stunning success of the Swiss high education, in which I landed late, taught me a lot. I had read Elias Canetti, by pure chance, and its reflections stuck. Reflecting now on the Swiss system should perhaps be an instructive exercise for improving the rest of the European academic network, and possibly the educational systems on a global scale especially my dearest and seemingly irreformable italian higher education. The heart of EPFL’s unstoppable progression is perceived to rest on the introduction of the tenure track process. Tenure track does not mean to call into question the meaning of tenure, generally perceived outside academia as unaccountability and a factory of fake retirements. Tenure is indeed a necessary virtue of academic life (as wonderfully described by Rosovsky, for instance). A selective tenure-granting procedure, instead, is key to Universities planning to grow and looking ahead, as it happen for the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne which graciously hosts me. Note that I did not say ‘employs’. That may be technically true but, as pointed out by Kantorowicz, the great medieval historian refugee from Hitler’s Germany who refused to sign an anti-Communist loyalty oath in time of McCarthysm and was dismissed, we should refuse under any circumstance to be classified as employees (of the State of California, in his case, of public and private Institutions in ours). We are not university employees subject to usual job discipline – to be a professor is to be of a different calling. In Kantorowicz’s own words: «There are three professions which are entitled to wear the gown: the judge, the priest and the professor. This garment stands for its bearer’s maturity of mind, his independence of judgement, and his direct responsibility to his conscience and his god.» This is because we are the University.

If I may, I quoted, regretfully but with a goal in mind, the Italian system of higher education as possibly irreformable. If I were to single out the core of this rather gloomy view, after a call of mine due a true vocation (I was due elsewhere, to my late father’s eternal regret), I would charge it to the peculiar blend of catholic ethics, as opposed to protestant, co-evolved with the environmental a social factors that inescapably shaper our meta-history. Too many to be discussed here, the key they can be subsumed by: Recognition and success are held with suspicion, merit goes unrewarded, a keen attention – fuelled by a totally pessimistic approach to human nature and its weaknesses – buries you with bureaucracy and prohibitions while nobody checks whether one’s duties are discharged. Sin and be pardoned, in the confessional tradition, whereas the Calvinist must simply behave instead. Because reward and punishment await you only in the afterlife, we need not show any decency in this one and carve out a self-centered niche where civil responsibility in non-existent and the State is always surrogated. Italy is the land of anonymous letters, of rules’ disregards at any level, of ubiquitous bad manners – and of treasures of intelligence and creativity. It is also revealing what Giacomo Rizzolatti, 2014 Brain Prize whose Lab is operating in Italy, recently said about the Italian system: merit is key to the University, maybe not for other civil servants -- there may not be great differences among employees of a generic office, but surely there are among professors. He felt disheartening the fight against bureaucracy that irons out enthusiasm, merit and drive to achieve. It is out of my unmovable faith in the intrinsic value of the Italian educational system and of my country’s many talents that, out of sentimental reasons, I chose to be still for a part of my time in my Alma Mater in Padua – and so on until I drop, unless rules beyond my control will determine otherwise.

The Swiss system, on the contrary, is based on trust – one that if breached calls for the system to react vehemently, and yet sees reward as the logical consequence of the work, appreciates success as the sign of the work behind it without treating it with suspicion and despise. It is a system made to trigger positive feedbacks from visionary policy.

The Swiss system exudes innovation, enthusiasm and strength. It is not simply a matter of resources, it is a matter of goals and vision. The idea that once you provide salaries and research infrastructure equal or better than those of the best private American universities, and then you add the culture and quality of life in Europe, then yours (asymptotically) are the best and the brightest. The idea is working wonderfully well for EPFL, which was established as a federal Institution just some 40 years ago (not 800 like in Padua) and now ranks among the very best Universities in the world. It is significant that the next embodiment of this attitude is the establishment of a research Center here in Venice (the EPFL Center for digital humanities and future cities). Is Venice the model of the city of the future? This is far from a wild shot, in my mind. In a world globally and instantly connected by the IT highways, it is information that moves, not you. The absence of cars, the beauty surrounding you, the quality of life and culture makes it a credible paradigm of the cities of tomorrow and of the intertwined fragility and resilience of the built and the natural environments, of social economic development facing ecosystem services. I believe that fleshing out the best science and technology to marry the world of cultural heritage is a wonderful idea, for both research and education. EPFL is opening an undergraduate program in Digital Science, and a matching graduate program in Digital Humanities, Digital Medicine and Digital Sociology (and hopefully Digital Urbanism in the future). This in my view embodies the mission of EPFL, and the farsighted view of the turf where the European University will lead the world in the future. The planned massive digitization of the celebrated venetian archives, the design of virtual museums, the pathbreaking monitoring and modelling of the built and the natural environments – they all seem like a fitting goal, in a race to produce new science and technology akin to the mapping of the human genome years before schedule or that giving EPFL its current lead in brain research worldwide.

4. In conclusion, everything I have said points to the fact that our mission in hydrologic research and education is a defined task, unaltered by current challenges and despite a general degradation of what surrounds us. Or so it seems, of course: every intellectual – if an academician may be defined as such in the face of Idealism-driven debates on the ‘two cultures’ -- has been a pessimist in his own time. Variants include past, present and future all equally dark, or the Dickensian gloom cast on future alone (the past shone with brightness and innocence, while the present looks dark and full of foreboding). Our unaltered task through the centuries, however, must lead us to reassess continuously how we exercise our profession yet training our students with a positive attitude. This I intend to do as long as I shall exercise my magistero.

In closing, I cannot fail to thank you, Rector Coderre, and the Faculty of the Université du Quebec and INRS, Université d’avant-garde, for this wonderful honor bestowed on me. Among those individuals who were instrumental in this honour, I would like to mention in particular Yves Bégin (INRS), Claudio Paniconi (INRS) and Mario Putti (Padua).

I am deeply indebted for my intellectual path to the many colleagues and friends that shaped my career and made this journey so enjoyable. I must acknowledge first and foremost my former students now colleagues, with whom it is such a pleasure to work, many of whom are here today (a gift in the gift of your choice of Venice as location for this ceremony). I would like to mention specifically my closest academic colleagues (Gedeon Dagan, Luigi Da Deppo, Alberto Bellin, Paolo Salandin, Riccardo Rigon, Marco Marani, Piero Ruol, Amos Maritan, Marino Gatto, Rafael L. Bras, Aronne Armanini, Marc Parlange, Paolo D’Odorico, Gianluca Botter, Andrea D’Alpaos, Enrico Bertuzzo, Aldo Fiori, Mario Putti, Luigi D’Alpaos, Stefano Lanzoni, Giovanni Seminara, Luigi Costato), my academic role models (Peter S. Eagleson, Giovanni Marchesini and Patrick Aebischer), all the members of the Laboratory of Ecohydrology of EPFL and in particular my lifelong friend and partner in research, Ignacio Rodriguez-Iturbe, master of contemporary thought and unmatched groundbreaker in research. My past and present affiliations with Padua, Trento, MIT, Princeton and EPFL are gratefully acknowledged. My thought goes, as usual in defining moments of my academic life, to Alessandro Marani, Donald R.F. Harleman and my late Master, Claudio Datei, whom I always remember with love and unmitigated admiration. Finally, my thought and heart goes to my beloved family, my now grownup children, Daniele, Carlotta and Tobia of whom I am so proud, and to my wife whose love and support have been the rock on which I founded all of my adult life.

Thank you.

in Venice, on may 8, 2014