A new way to experience traditional music of Afghanistan

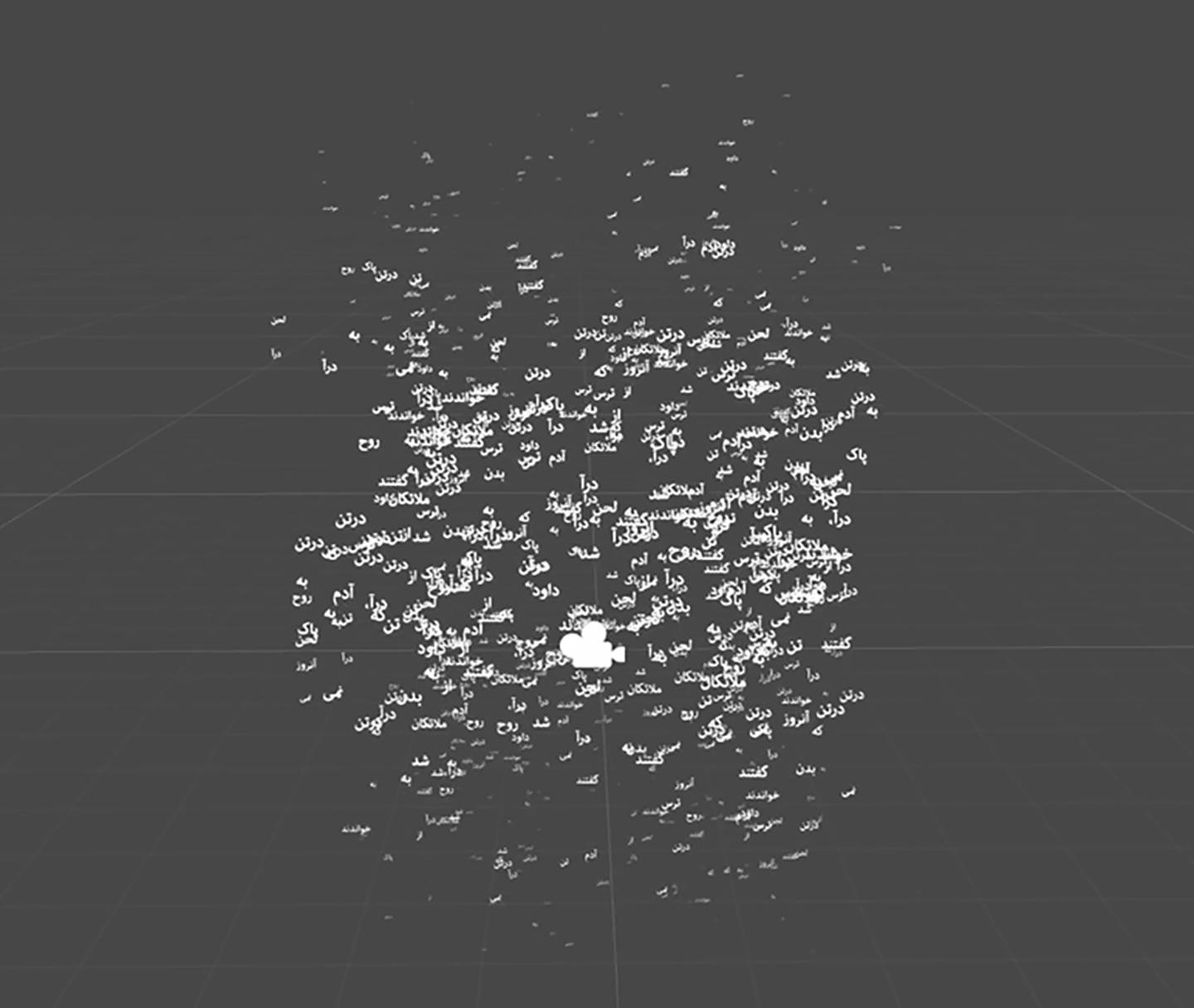

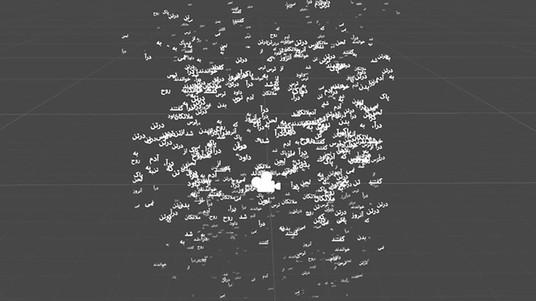

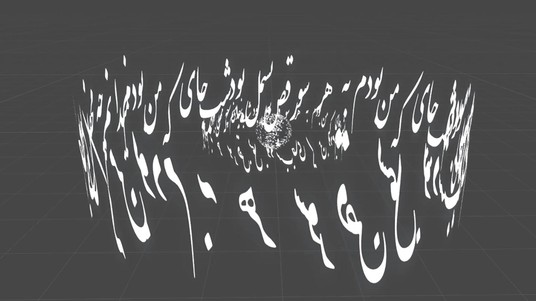

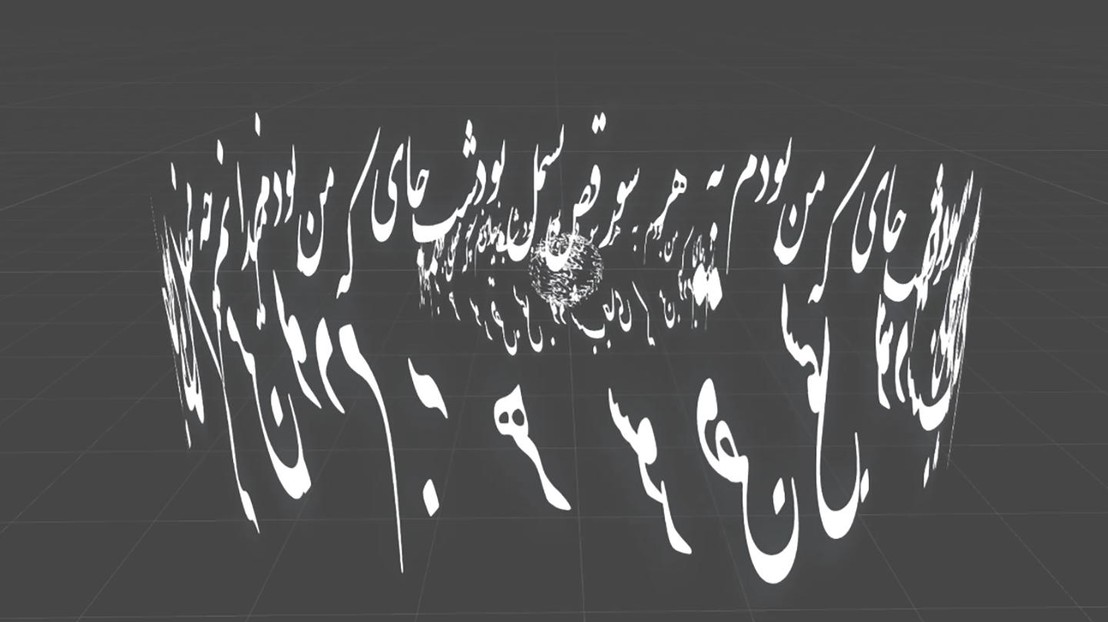

Image from Mathieu Clavel's immersive visualization of one of Ustad Sarahang's musical recordings. © Mathieu Clavel

(Summer Series): Mathieu Clavel, a master’s student in the College of Humanities (CDH) Digital Humanities Institute, is bringing musical heritage from Afghanistan to life using tools from data science and virtual reality.

When Mathieu Clavel set out to create an immersive virtual experience of a cultural heritage archive as part of his project for a digital humanities master’s course, he decided to go beyond the traditional project framework to propose his own concept, inspired by a long-standing passion for traditional music of Afghanistan and the Middle East.

“I was already collecting musical recordings from one of Afghanistan’s greatest artists of the last century, Ustad Mohammad Hussein Sarahang. So, it felt really natural for me to work on that archive, because nothing like it really exists online for this kind of music,” explains Clavel.

In addition to his master’s studies in the CDH Laboratory for Experimental Museology (EM+), led by Professor Sarah Kenderdine, Clavel regularly works as a concert organizer and musical tour guide in Iran. He is fluent in several instruments including the rubab – a stringed instrument similar to the lute that features prominently in many of Ustad Sarahang’s recordings.

Bringing intangible heritage to life

Clavel has assembled a large digital archive of some 750 recordings of Ustad Sarahang singing ghazal, one of the forms of classical Persian poetry. Now, he is in the process of augmenting each recording with metadata about the song’s technical and musical properties, and developing a website for users to browse the curated recordings.

“I am trying to identify the lyrics and musical mode of each piece, which takes a lot of time, so when the website is up I am hoping to use a crowdsourcing approach,” he says.

He has also developed a unique concept for immersive visual experiences of these recordings, using representations of the lyrics in Persian calligraphy. The broader goal is to see if a virtual reality headset or a fulldome video projection environment (such as one might see in a planetarium) could be an effective way for the public to engage with this or other kinds of music.

Clavel developed a proof-of-concept in the form of a 3.5-minute immersive experience, using a head-mounted virtual reality display, of one of Ustad Sarahang’s recordings. He now plans to adapt this proof-of-concept to a fulldome context, to bring another dimension to the curation and exhibition of the archive.

For Clavel, these digitization and visualization technologies are a crucial opportunity to bring to life intangible cultural heritage that people may otherwise never discover.

“It’s more difficult to deal with intangible heritage because by definition it is not set in stone, and can easily disappear,” he says. “If you want this art form to live on, you must expand the audience for it. This project is about creating this kind of engagement, and creating a visual experience that goes beyond just an old MP3 recording. Hopefully, it will be a gateway into this music and this universe.”

A digital humanities showcase

Clavel will demonstrate his project, using the head-mounted virtual reality experience, at the EPFL Open Days on September 14th and 15th. The event will also feature several other activities and exhibits for the public featuring research in the digital humanities – a field in which data science methods and digital technologies are used to study art, history, and culture.

“The digital humanities are a way to reconcile two parts of my own life, with engineering and scientific studies on one side, and the arts and cultural studies on the other,” Clavel says. “For me, the digital humanities are important, because they allow us to use tools from science and engineering in the service of art and culture.”

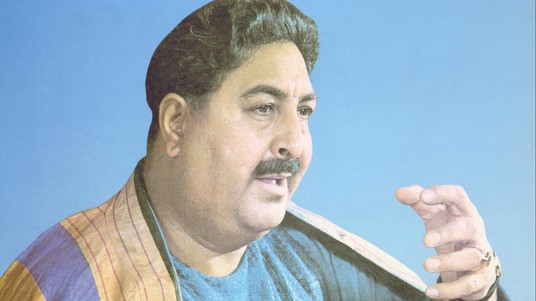

Ustad (Master) Mohammad Hussain Sarahang was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1924. He was the country’s most famous musician of his generation in the traditional music form of ghazal, and recorded many radio programs during his prolific career. He passed away in Kabul in 1983, leaving many recordings which together provide a unique source of musical heritage.