A new anthology highlights the legacy of Rem Koolhaas

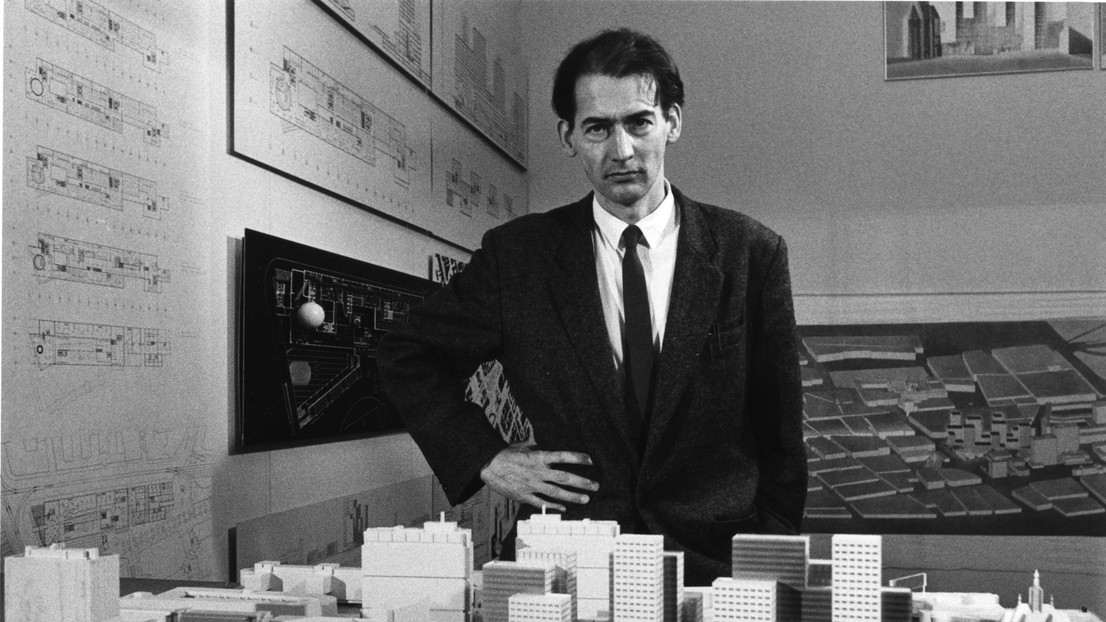

Rem Koolhaas presents his project for the city hall of The Hague in 1986. © DR

Interviews, reviews, articles, essays, opinions and competition reports published all over the world in relation to Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas – some of which have been translated into English for the first time – have been collected in a new anthology. We discussed the architect’s legacy with the anthology’s author, Christophe van Gerrewey, a tenure-track assistant professor at EPFL in the theory and history of architecture.

“I regard myself as a descendent of the true Modernists,” a young Rem Koolhaas told Dutch journal wonen-TA/BK in 1978. He also said he was not worried about his utilitarian approach to architecture not being fashionable at the time.

Highly self-assured, even arrogant according to some, Rem Koolhaas was already actively creating his own myth. He would go on to become one of the key architects of the second half of the 20th century, a controversial “starchitect,” a provocateur, hated and admired in equal measure. Three years before that interview took place, he founded his own practice, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), in New York. His 1978 manifesto extolling the virtues of Manhattan, Delirious New York, has become a cult classic. From the United States to China, his designs have showcased his radical thinking for more than 40 years now. The same is true of his essays and Harvard lectures.

However, his influence on contemporary architecture remains hard to pin down. To better understand how his work has been received around the world, Christophe van Gerrewey, a researcher and tenure-track assistant professor at EPFL in the theory and history of architecture, has put together an anthology of 150 texts from all corners of the globe and published between 1975 and 1995, some of which have been translated into English for the first time: “OMA/Rem Koolhaas, A Critical Reader from Delirious New York to S,M,L,XL” (Birkhäuser). The anthology represents a genuine salvage operation, to save texts that would otherwise have been consigned to history. The book is illustrated with dozens of magazine covers featuring the architect’s image – from the specialist press to Vogue – both highlighting his global popularity and raising questions about it.

The anthology focuses on the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), from the time the practice was set up in 1975 to the publication of the book S,M,L,XL in 1995. During that period, you say that architecture sought to be on an equal footing with literature and the visual arts. Does the anthology shed light on Rem Koolhaas’s role in that process?

During that period, architecture undeniably became a much more popular part of culture than before. Rem Koolhaas belonged to a generation of architects who attracted attention from the mainstream press because of his eloquence, his ability to pick up on trends and a certain sense of self-promotion. The texts collected in my book help us to understand him. He’s also someone who presented architecture as an intellectual activity and as something fun. His buildings are highly inventive and sometimes very unexpected. But we can’t really say that architecture has managed to attract the same kind of attention on the culture pages as literature, the movies or theater.

In your opinion, what is the influence, relevance and legacy of Rem Koolhaas’s work in 2019?

It’s interesting to study his writings and designs, not just qualitatively, but also because they reflect their era. In 1978, Delirious New York was a defense of Manhattan at a time when the city was regarded as a dangerous and unpleasant place to be. Instead, Koolhaas regarded it as an accumulation of original formal inventions, one example being Coney Island. We see here his tendency from the start to take an interest in unpopular subjects just before they became popular. The following decade, in 1989, he designed a terminal for the Sea Trade Center in Zeebrugge, which would become a symbol of open communication and European unification, embodying Europe’s optimism in the post-Cold War period. In some ways, the project also showed the drawbacks of the European project: it was overly focused on commerce and turned into a money pit.

What about the 1990s?

In the early 1980s, his firm was building low-cost housing, but we see those kinds of projects subsequently disappear from his practice. That reflected the shift in housing policies away from socialist ideals. In 1992, however, OMA built what critics regard as its most successful building: the Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam. The building is perfectly balanced, capable of attracting the attention of its visitors while also being an ideal setting for the works of art it contains. But probably his most vital work during the period was his book S,M,L,XL, which any self-respecting architect should own.

What makes the book so special?

As things stand today, it is the most recent major book on architecture, the one that has had the most impact, attracting reviews all over the world even two years after it was published. There was also an exhibition dedicated to it, as my anthology shows. However, at 1,300 pages long, S,M,L,XL isn’t a book meant to be read, but to be browsed. Bruce Mau’s graphic design is a key feature of it, and it’s more of an object than a book. In that sense, you could say that it foreshadowed the culture of channel-hopping or even browsing the internet.

Rem Koolhaas is known for making provocative statements, particularly in the media. Does your anthology allow us to separate fact from fiction?

The texts that I assembled show that some of his slogans, such as “Fuck context”, played a role in both his success and the criticisms made of him. In the case of “Fuck context”, we see that what Koolhaas was actually saying was that architecture should not imitate that which already exists and should not be bound by a restrictive context. So he wasn’t saying that architects should be arrogant and insensitive to their context, it was a way of thinking about context in a more complex way.

The anthology shows how architectural criticism developed in the late 20th century. Why is it important to read what critics were writing 20 years ago?

The anthology shows that the critiques are sometimes more interesting to read than the texts written by Rem Koolhaas himself. For example, in “The Generic City” section of S,M,L,XL, the architect decries the idea that all cities look like airports. The anthology shows how critics responded to that assertion. Above all, the book shows that criticism between 1975 and 1995 was more tangible than it is today. Appearing on the cover of a magazine was a real accolade, and that’s why I included some of those covers in the first few pages of the book. I also wanted to remind readers that the opinion of intellectuals does count for something and does contribute positively to the debate in our society, at a time when Twitter sometimes seems to dominate the debate. One of architecture’s merits is that it prompts people to think about and take a moral stance on how society is developing. In that sense, Rem Koolhaas’s radical approach gave intellectuals constant food for thought, whether they were for him or against him.

In light of your anthology, how do you present Rem Koolhaas to your students today?

On one hand, he’s someone who’s broadened the scope of architecture in the world and shown that it can be pleasurable and fun. On the other, everything he stood for is now condemned and considered reprehensible. For example, he based many of his projects on economic growth and capitalism – choices that are now being made obsolete by the climate crisis. But actually, by helping us understand the excesses of the periods in which he’s worked, he’s very valuable. His mistakes provide opportunities to learn. He’s also an architect who can never be fully understood, because he knows how to remain unpredictable. Finally, he’s someone who’s very self-aware, and who has always been wary of lies and illusions. In that sense, he can be a source of inspiration. Taking his fun and playful approach to architecture in today’s world is a challenge for any young architect.

The Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam, achieved in 1992. © OMA

The Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam, achieved in 1992. © OMA