A multilingual dictionary accessible to all

© 2014 EPFL

A multilingual dictionary, benefitting from the contributions of Internet users, available for free on the Web in all of the world's languages: this is the aim of Kamusi. However, developing such a tool is a veritable technological challenge, because each language is said to have an average of at least 100,000 words that often have several meanings. Given that there are currently around 7,000 living languages around the world, finding equivalencies for all of the words in all of the languages amounts to searching for needles in haystacks piled as far as the eye can see. How to handle such a challenge? By having an anthropologist slash language enthusiast work with a computer scientist who is passionate about Big Data.

Some languages are written, but not all. Some languages have several cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, etc.), which are a series of declensions of the same word, whereas other languages have none at all. Likewise, languages such as Classical Arabic can have up to six different plural forms, which offer so many variations of the same word. German has three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter) whereas other languages draw a distinction between animate (living) and inanimate (non-living) objects. Most languages contain words that do not really exist anywhere else, such as the subtle nuances between different words that mean "white" or "snow" in Inuit.

Bilingual dictionaries versus multilingual dictionaries

Faced with all of these peculiarities and many more besides, traditional dictionaries generally limit themselves to bilingualism, which enables one to link words of equivalent meaning in two different languages. This approach, however, becomes more complicated when an effort is made to find equivalent expressions. A well-known example is the expression "It’s raining cats and dogs", which certainly could not be translated literally. The same holds true for the equivalent French expression, "Il pleut des cordes", which, while less humorous, is every bit as imaginative. Online translation tools reflect the difficulty of including the specificities of each language, or even of each word. Martin Benjamin, who has a PhD in Anthropology and a passion for linguistics explains: "If you introduce the expression "the spring in her step" in any online translation tool, what you get in French is typically something along the lines of: "le ressort dans son étape". A more adequate translation would be: "sa démarche élancée". These tools are based on a word-for-word approach but often words have many different meanings. You have to know which meaning is the right one."

The impossibility of a multilingual dictionary using previous methods of linking words through spelling instead of meaning

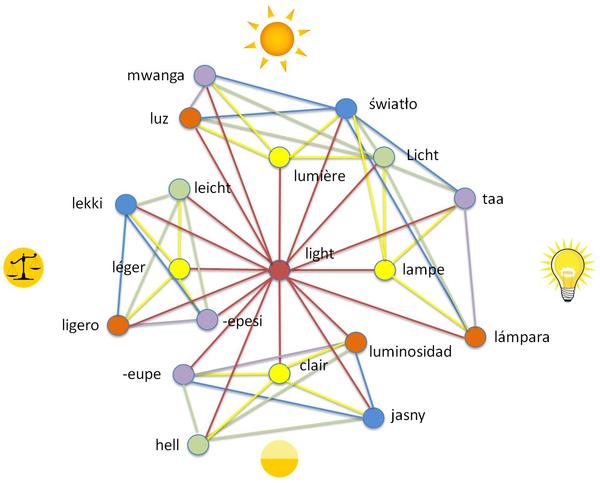

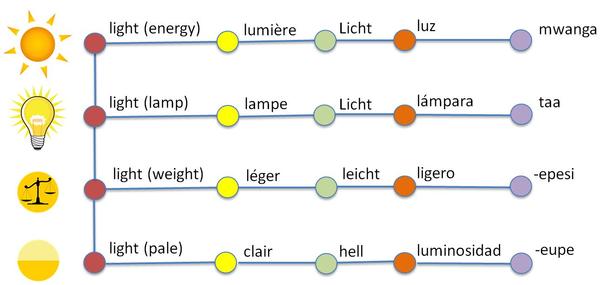

Creating a network of languages

In the case of a multilingual dictionary, all of the meanings of words are theoretically linked together in all languages, which allows one to perform automatic verifications within the network of languages. Indeed, if "light" means "lumière" in French, but also "léger", then the equivalent words in German are "Licht" and "leicht". These two German words can then be cross-referenced to "light" in English while nevertheless maintaining the distinctions that exist in French or in other languages. Therefore, a multilingual dictionary would allow one to differentiate between the various possible meanings of a given word by deducing equivalencies in the other languages.

Kamusi links languages based on concepts, which makes possible accurate multilingual connections between any number of languages.

"Kamusi" or dictionary in Swahili

The Kamusi project began in 1994 when Martin, an anthropologist specialized in Africa at the time, noticed that there was no good Swahili dictionary even though it is the most frequently used language on the African continent (at least 100,000,000 people use it on a daily basis). Moreover, dictionaries are expensive to produce and costly for buyers. Nowadays, at least 1/3 of the population of African countries has a cell phone (i.e. at least one cell phone in 80% of households). In many cases, these phones can also be used to connect to the Internet. Cell phone technology is booming and smartphones are becoming more affordable. Aware of this phenomenon, Martin began developing an online English-Swahili dictionary, mostly with the help of contributions from volunteers with access to the Internet. Today, this dictionary contains 60,937 words. He then decided to pursue the multilingual dictionary path but soon realized that only an extremely complex IT infrastructure could process all of this data and connect entries in a meaningful way. This is where Professor Karl Aberer enters the picture.

Switzerland as the ideal location

After meeting Karl, who happens to be a top-notch specialist in Big Data, Martin chose to pursue his project at the EPFL in Switzerland, a multilingual country by definition, home to both Latin and Germanic languages and multiple dialects. A multilingual dictionary would be a very practical tool for many people who work in two, three or even four languages. "Multilingual dictionaries are becoming an essential building block for semantic technologies that are grounded in linguistic techniques and are applicable beyond a single language. From a computer science perspective also the use of crowd-sourcing methods for their construction is a fascinating challenge," explains Karl.

Once the IT infrastructure has been programmed, there will be a need to not only import data from pre-existing dictionaries, but also to rely on communities of Internet users to verify and confirm the meanings of words. Contributors will be able to express their views regarding equivalents in different languages and even give their own definitions of words when none exist in any other dictionary. Internet users will be able to assess the accuracy of contributions and validate the result. After a certain number of validations, an entry will be given a high reliability rating.

The Kamusi multilingual dictionary project is a unique scientific challenge, since the raw materials used – words and languages – are fascinatingly complex. Thanks to computer science and communication systems, such a challenge is now conceivable.

© US National Science Foundation / Sandy Schaeffer Photography

Martin Benjamin with high-ranking officials at the White House Big Data Event, "Data to Knowledge to Action", in Washington D.C., November 2013. Here he is receiving recognition in the context of the federal research program "Networking and Information Technology Research and Development".