A fulldome world premiere for the National Museum of Australia

© Sarah Kenderdine & Peter Morse for NMA

“Songlines: tracking the Seven Sisters exhibition” will be running from 15 September 2017 to 25 February 2018. Thanks to the full immersion inside the digital dome, visitors will be taken on a journey across the Australian desert in this Aboriginal-led exhibition about the epic Seven Sisters Dreaming — Travelling Kungkarangkalpa.

Authors: Sarah Kenderdine, Peter Morse, Cedric Maridet in collaboration with NMA for DomeLab*

Authors: Sarah Kenderdine, Peter Morse, Cedric Maridet in collaboration with NMA for DomeLab*

* DomeLab is a research infrastructure project led by Professor Sarah Kenderdine, University of New South Wales, supported by the Australia Research Council.

[The following is an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue chapter].

Landscape is fluid – it flows around us and encompasses us. It is not, however, external to the individual; landscape is an assembly of sensory information which generates a seen and felt experience of the world. It is a symbolic constitution of the environment within which humans exist. Paul Faulstich, 1991

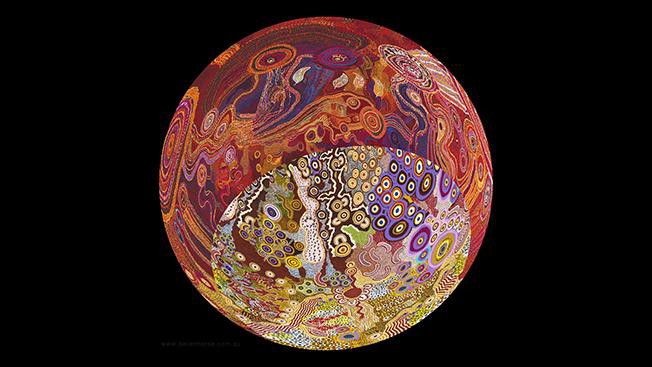

A focal point of the “Songlines: tracking the Seven Sisters exhibition” at the National Museum of Australia is a dome experience conceived to immerse audiences in significant sites of the Seven Sisters (Kungkarangkalpa) at Walinynga (Cave Hill). This digital sanctuary simultaneously expresses the sphere of the world around us, the sky above and the ground below, enveloping viewers in depictions of the Seven Sisters as they travel through country avoiding the unwanted attention of the lustful Wati Nyiru. As these creation beings travel, they leave land formations in their wake and later continue the chase evident in Pleiades and Orion in the southern night sky. The architectonic form of the dome provides an ideal spatial canvas, inviting viewers inside to lie down and look up – travelling Kungkarangkalpa.

Archaic dome theatres are typified by the rock art caves found throughout Australia, some of the oldest painted arcades in the world. Discussing the appeal of projection domes in the present day, media theorist Nick Lambert argues that these ancient caves, where etchings and paintings were animated by fire and torchlight, represent the beginnings of cinematic imagery, and were arguably the first immersive experiences created by humankind.

The perceived hemispheric curvature of domes has been rendered architecturally by many cultures throughout the world and used to enfold the most sacred environments. From Buddhist stupas and Jain temples to Islamic mosques and Christian cathedrals, dome constructions are places of ritual, communion, and transcendence. With both internal and external surfaces infused with iconography and geometric symbolism, domes continue to represent the worldviews of many traditions. Throughout the ages, such arched enclosures have often been used as surfaces upon which to represent ‘psycho-cosmological constructs’, decorated with ‘incorporeal archetypes’.

A dome’s ability to completely envelope the visual field of viewers in a mediated environment has continued to provide a revolutionary framework for pioneers in the arts and sciences. The concept of an ‘experiential’ domed environment was created by the art and engineering collective Experiments in Art and Technology in the Pepsi Pavilion for Expo ’70 in Osaka. Described at that time by art critic Barbara Rose as a ‘theatre of the future’ and a ‘living responsive environment’, this dome was envisioned as a ‘total instrument’ to be played by the participants, providing them with ‘choice, responsibility, freedom, and participation’. Such early developments in dome projection theatres emerged from attempts to simulate the ‘spherical gestalt of the human visual field’ and were designed to exploit and extend sensory perception. Many of the pioneers involved in conceiving dome experiences from the 1960s onwards believed that spatialised multisensory embodiment made possible in a dome would enhance the capacity and speed of human cognition, and ultimately a sense of presence or being there.

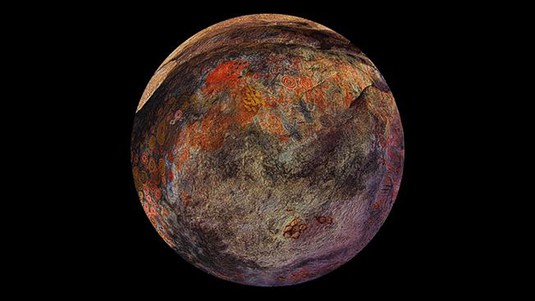

Travelling Kungkarangkalpa invites viewers to enter two distinct journeys: one as witness to Walinynga, with its ochre-painted ceiling giving an animated canopy of Kungkarangkalpa. The cave was photographed in three dimensions for the first time, allowing visitors intimate views of the stories contained in its sandstone folds. The other journey immerses visitors in a series of projected artworks of this Tjukurpa, following the Seven Sisters as they travel country. In the final scene, three-dimensional models of the extraordinary trussed grass tjanpi figures are seen taking flight, prefiguring their final destination in the night sky.

Embodied space is the location where human experience and consciousness takes on material and spatial form. Setha M Low, 2013

Travelling Kungkarangkalpa: Resolution 4096x4096. Runtime:15mins.

Contributors:

Animation: Brad May

Photogrammetry: Paul Bourke

Field assistant: Chris Henderson

Paul Faulstich, ‘Mapping the mythological landscape: An Aboriginal way of being‐in‐the world’, Philosophy & Geography, vol. 1, no. 2, 1998, 197–221 (p. 201).

Nick Lambert, ‘Domes and creativity: A historical exploration’, Digital Creativity, vol. 23, no. 1, 2012, 5–29.

David McConville, ‘Cosmological cinema: Pedagogy, propaganda, and perturbation in early dome theaters’, Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, vol. 5, no. 2, 2012, 69–86 (p. 69).

Barbara Rose quoted in McConville, ‘Cosmological cinema’ (p. 82).

McConville, ‘Cosmological cinema’ (p. 77).

Setha M Low, ‘Anthropological theories of body, space, and culture’, Space & Culture, vol. 6, no. 1, 2003, 9–18 (p. 9).