Observing brain diseases in real time

© 2016 EPFL

An innovative tool allows researchers to observe protein aggregation throughout the life of a worm. The development of these aggregates, which play a role in the onset of a number of neurodegenerative diseases, can now be monitored automatically and in real time. This breakthrough was made possible by isolating worms in tiny microfluidic chambers developed at EPFL.

For rent: 32 individual rooms for a combined surface area of 4cm2, heating and food included! Biologists and microfluidics specialists at EPFL have joined forces and developed a highly innovative research tool: a 2cm by 2cm ‘chip’ with 32 independent compartments, each of which is designed to hold a nematode – a widely used worm in the research world. The device is described in the journal Molecular Neurodegeneration.

“Unlike conventional cultures in petri dishes, this device lets us monitor individual worms rather than a population of them,” said Laurent Mouchiroud, from EPFL's Laboratory of Integrative Systems Physiology.

Freeze frame

Each of these ‘cells’ is fed by microfluidic channels. These allow variable concentrations of nutrients or therapeutic molecules to be injected with precision. The ambient temperature can also be adjusted.

Each worm is observed through a microscope throughout its life. However, for more detailed investigations and very high resolution images, the worms need to be immobilized. “For this we use a temperature-sensitive solution,” said Matteo Cornaglia, from the Laboratory of Microsystems. “We inject it in liquid form at 15°C, then bring the temperature up to 25°C, which transforms it into a gel. The worm is immobilized in just a few minutes, then we bring the temperature back down and rinse out the solution – and the worm is able to move again.”

Protein aggregates in the cross-hairs

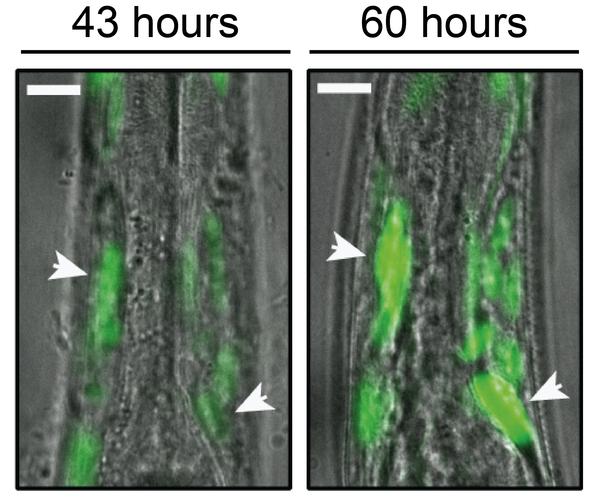

This method is fully reversible and does not affect the nematode’s development. Using it, researchers can observe the formation of protein aggregates linked to several neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s. The same worm can be photographed several times, as the clusters develop. “This is totally new, and it will help us learn more not only about how these aggregates grow, but also about the tissue in which they form,” said Mouchiroud. “In addition, we have already been able to test and observe the effect of certain drugs on how the clusters form.”

Nematodes are very useful models for studying a number of human diseases. In many cases, they obviate the need to experiment on rodents. But until now, handling nematodes was a delicate affair. By simplifying the process, this new technology should accelerate research on numerous afflictions and how they are treated.