Le Corbusier, a revised vision of the architect and his work

Roberto Gargiani, professor at Theory and History of Architecture Laboratory 3

Roberto Gargiani unveils a different vision of Switzerland's most famous architect - Le Corbusier. Published at EPFL Press.

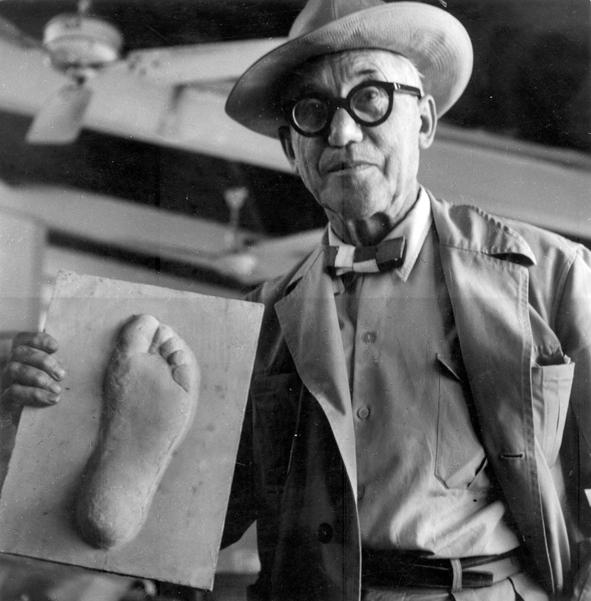

Roberto Gargiani, professor at EPFL’s Theory and History of Architecture Laboratory 3, has spent the last six years carefully studying Le Corbusier’s lesser-known archives and visiting the buildings he designed from 1940 to his death in 1965 with his research assistant and co-author Anna Rosellini. A different Corbusier comes into focus; poet, mystic, philosopher and artist.

You recently published a book about Le Corbusier’s work and life after World War II. Why research this period specifically?

For Le Corbusier, the Second World War and its horrors made him completely rethink the notion of the civilisation machiniste that had been central to his buildings constructed in the 20s and 30s. Le Corbusier saw the war as the machine being turned against civilization itself. What better place to start than when he began to redefine himself? We let him lead us away from his antecedent vision of architecture that has tended to defined how we look at him until this very day.

Le Corbusier is the architect with probably the most books already written about him. What are you trying to accomplish with your current research?

Most books written about Le Corbusier are almost always seen through the looking glass of the generation writing about them, taking us increasingly further away from a scientific and historical understanding. I felt a re-boot was necessary. Little by little a new vision of his person and his later work came into focus; the influence of India on his thought and work after World War II, his understanding of the role of photography in architecture and his surrealistic techniques as an architect, sculpture and tapestry designer.

Most books written about Le Corbusier are almost always seen through the looking glass of the generation writing about them, taking us increasingly further away from a scientific and historical understanding. I felt a re-boot was necessary. Little by little a new vision of his person and his later work came into focus; the influence of India on his thought and work after World War II, his understanding of the role of photography in architecture and his surrealistic techniques as an architect, sculpture and tapestry designer.

How would characterize this new vision?

If we look specifically at the period after World War II until his death in 1965, we see an artist who was constantly searching for new ideas, ready to transform his notion of architecture and subsequently of all modern architecture. When going through these archives, I discovered an architect who was at the same time a poet, a philosopher and a visionary. He is, still today, at the avant guard of architecture.

For example, his research on what is now called “climate adapted architecture,” has only been cursorily explored. Le Corbusier was already designing buildings adapted to local climatic elements in the 40’s and 50’s using a technique he called the “climate grid,” or grille climatique. Sunlight played an essential role in how he conceived architecture, and he was already thinking about how to draw as much light into the living spaces without raising the temperature.

Your research focuses greatly on the notion of Béton Brut, could we finish this interview with a word about that?

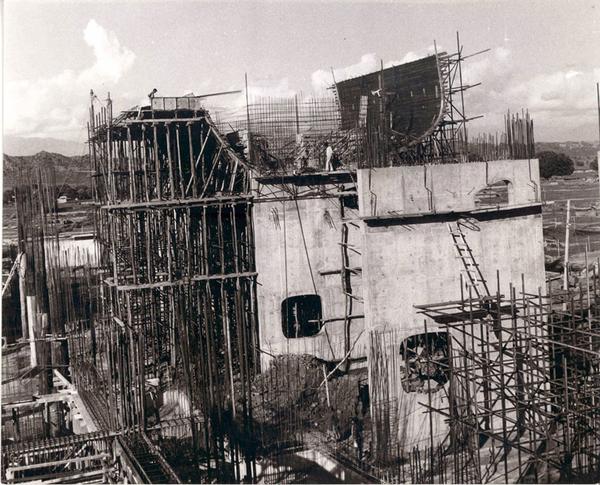

Do not forget that Le Corbusier was an artist and an artisan. He saw beauty in the spontaneous creation of concrete being struck from the formworks and wanted these marks and even mistakes to be part of the esthetic qualities of the building. He wanted his concrete to be left raw, not polished nor glossed over. His vision of what brut signified also transformed over his life’s work, from a maniacal control over each element to embracing hazard as a positive force, perhaps as a direct result of time spent in India.

It seems that Le Corbusier was receptive to many cultural influences...

He took inspiration from his travels to India and his readings of the Surrealists while never forgetting his origins as a decorator from La-Chaux-de-Fonds. From these influences he infused his buildings with tapestries of his own design, sculptures embedded directly into the concrete taken from his own drawings, as well as color schemes that were meant to evoke emotional reactions. Modern architecture is still being defined by his vision and we hope this research will bring new perspectives to his vast influence.

“Le Corbusier Béton Brut and Ineffable Space 1940-1965: Surface Materials and Psychophysiology of Vision” by Roberto Gargiani and Anna Rosellini. EPFL Press ISBN 978-2-940222-50-6