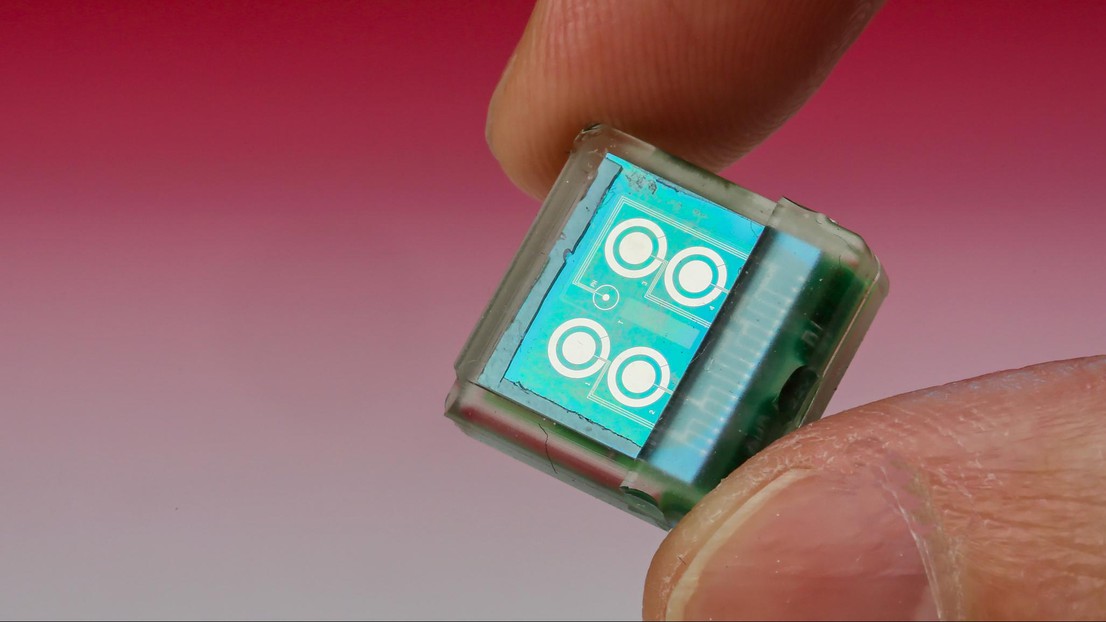

A chip placed under the skin for more precise medicine

© Alain Herzog / EPFL 2015

It’s only a centimetre long, it’s placed under your skin, it’s powered by a patch on the surface of your skin and it communicates with your mobile phone. The new biosensor chip developed at EPFL is capable of simultaneously monitoring the concentration of a number of molecules, such as glucose and cholesterol, and certain drugs.

The future of medicine lies in ever greater precision, not only when it comes to diagnosis but also drug dosage. The blood work that medical staff rely on is generally a snapshot indicative of the moment the blood is drawn before it undergoes hours – or even days – of analysis.

Several EPFL laboratories are working on devices allowing constant analysis over as long a period as possible. The latest development is the biosensor chip, created by researchers in the Integrated Systems Laboratory working together with the Radio Frequency Integrated Circuit Group. Sandro Carrara is unveiling it today at the International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) in Lisbon.

Autonomous operation

“This is the world’s first chip capable of measuring not just pH and temperature, but also metabolism-related molecules like glucose, lactate and cholesterol, as well as drugs,” said Dr Carrara. A group of electrochemical sensors works with or without enzymes, which means the device can react to a wide range of compounds, and it can do so for several days or even weeks.

This one-centimetre square device contains three main components: a circuit with six sensors, a control unit that analyses incoming signals, and a radio transmission module. It also has an induction coil that draws power from an external battery attached to the skin by a patch. “A simple plaster holds together the battery, the coil and a Bluetooth module used to send the results immediately to a mobile phone,” said Dr Carrara.

Contactless, in vivo monitoring

The chip was successfully tested in vivo on mice at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB) in Bellinzona, where researchers were able to constantly monitor glucose and paracetamol levels without a wire tracker getting in the way of the animals’ daily activities. The results were extremely promising, which means that clinical tests on humans could take place in three to five years – especially since the procedure is only minimally invasive, with the chip being implanted just under the epidermis.

“Knowing the precise and real-time effect of drugs on the metabolism is one of the keys to the type of personalised, precision medicine that we are striving for,” said Dr Carrara.